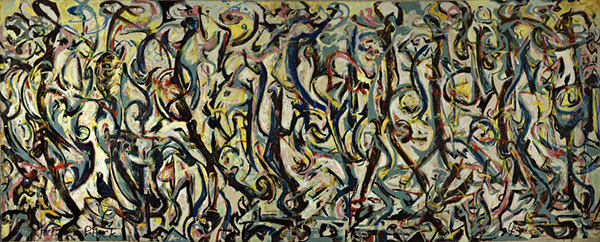

At the Getty Center: Installation of Jackson Pollock’s Mural, 1943. Oil and casein on canvas, 95 5/8 x 237 3/4 in. The University of Iowa Museum of Art, Gift of Peggy Guggenheim, 1959.6. Reproduced with permission from The University of Iowa

Jackson Pollock is arguably among the most influential painters in American history, and his painting Mural is widely recognized as a crucial watershed moment for the artist.

The exhibition of Pollock’s Mural, opening at the Getty Center on March 11, is an incredible opportunity to see the landmark painting up close.

Mural was Pollock’s first commission by legendary art collector Peggy Guggenheim, and the work has been in the University of Iowa’s art collection since she donated it in 1951. But scientists and conservators at the Getty have been lucky enough to have this artwork “living” in the conservation studio for the last 21 months.

Following extensive study and treatment by the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Getty Conservation Institute, the painting will be exhibited alongside new research that sheds light on the artist’s process.

Mural, 1943, Jackson Pollock. Oil and casein on canvas, pre-conservation, 95 5/8 x 237 3/4 in. The University of Iowa Museum of Art, Gift of Peggy Guggenheim, 1959.6. Reproduced with permission from The University of Iowa

The analysis and conservation work was jointly undertaken by Tom Learner and Alan Phenix from the Conservation Institute, and Yvonne Szafran and Laura Rivers from the Museum. Earlier this week in the paintings conservation studio, I talked to them about their work on Mural, and what they’ve discovered.

Interestingly, the painting was likely rolled and unrolled at least five times as it moved from Pollock’s studio, to Guggenheim’s entrance hall, to Vogue Studios for photography, to New York’s Museum of Modern Art, to Yale University, and finally, in 1951, to the University of Iowa.

Although this kind of treatment was common at the time, the painting’s early itinerant history took a toll on its condition, according to Yvonne Szafran, the Getty Museum’s Head of Paintings Conservation. The paint began to flake, and the weak original stretcher caused the painting to develop a pronounced sag. By 1973, its structural condition was in need of attention, and a conservation treatment was carried out in Iowa to stabilize it. This included adhering a lining canvas with wax-resin to the reverse, replacing the original stretcher with a sturdier one, and varnishing the painting.

Yvonne Szafran in the Getty Museum’s paintings conservation studio with Jackson Pollock’s Mural.

By 2009, it was evident that further conservation intervention was needed, and experts from the Getty were invited to Iowa to assess the condition and display of the painting.

Laura Rivers, associate conservator at the Museum, added that while the 1973 treatment successfully consolidated the paint, it also made the sag in the canvas a permanent feature, with the adhesive locking the distortion into place. When the painting was re-stretched, the distortion meant that portions of the unpainted margins were now visible on the front of the painting. The varnish applied in 1973 also dulled the surface. It was time to do something.

Laura Rivers works on Jackson Pollock’s Mural in the Getty Museum’s paintings conservation studio

In July 2012, the painting was transported to the Getty Center for an in-depth study and conservation treatment. Art historical research, conventional methods of treatment and analysis, and some of the latest developments in technical imaging were used to provide new information and insights into the painting and its creation and present Mural in the best possible manner.

One exciting discovery, Getty Conservation scientist Alan Phenix told me, is that Pollock’s initial paint marks were likely made in four highly diluted colors—lemon yellow, teal, red, and umber—all applied wet-on-wet and still visible in several areas of the painting. This presents the intriguing possibility that one of the most prevalent myths, that Pollock painted the monumental work in one all-night session, might be partially true.

“It looks as if Pollock did finish some kind of initial composition over much of the canvas very rapidly, perhaps even in a single all-night session,” said Tom Learner, Head of Science at the Conservation Institute. “However, the majority of paint layers on Mural were not part of this session, and were in many cases added over earlier applications of paint that had already dried, indicating that several days or even weeks would have passed between painting sessions.”

Further analysis also provided new information about the paints Pollock used to create his masterpiece. While most of the work was created on Belgian linen canvas with high-quality artist’s oils, the investigation yielded another interesting surprise: simple white house paint. The house paint was used specifically to regain some pockets of areas of white space or “air” after the majority of the work had already been painted.

The team also investigated whether Pollock might have laid the canvas on the floor to drip paint onto the canvas, as he famously did in later years.

Tom Learner (left) and Alan Phenix of the Getty Conservation Institute with Jackson Pollock’s Mural

“There are several areas of pink paint on Mural where we thought Pollock may have dripped it onto a canvas lying flat on the studio floor,” Tom told me. “However, we were able to achieve the same results by manipulating an oil paint and flicking it at a test canvas placed upright, so it seems unlikely that he laid this painting horizontally to apply paint to the canvas.”

“Even so, you can certainly glimpse in the application of the splattered paint in Mural how Pollock’s style is evolving,” added Yvonne. “It’s a hint of things to come.”

For the conservation treatment carried out at the Getty, conservators first removed the aged varnish on the surface, which made an important visual change to the depth and surface of the painting.

Another major conservation challenge was dealing with the exposed edges of the painting and the pronounced sag in the original canvas. The stretcher that holds the canvas needed to be remade to properly bear the weight of the artwork, so the team began to think of ways in which the shape of the painted surface could be incorporated into the new stretcher design.

Instead of simply replacing the stretcher, the team began to consider making a slightly curved stretcher that would follow the existing painted edges, thereby returning all areas of unpainted canvas to the sides of the stretcher, Tom and Yvonne told me. Throughout the entire process, the team said, they let the painting speak for itself, to let them know if it could be put on a curved stretcher.

The team created painstaking mock-ups, researched all the variables, talked with other experts, and decided it was worth the undertaking. The results are breathtaking.

The exhibition at the Getty Center examines the materials and techniques used to create Mural, explores some of the legends surrounding the work, explains how it has changed since it was completed, and discusses its recent conservation treatment at the Getty. It delves into a transitional moment in Pollock’s career as he moved toward the experimental application of paint that would become the hallmark of his technique.

It’s an incredible transitional moment for Pollock, immortalized on canvas, and it’s a fleeting opportunity for visitors—Mural is only at the Getty Center until June 1.

I wonder if we will be allowed to take pictures of it….and, if so, can a camera really capture Mural’s monumental presence?