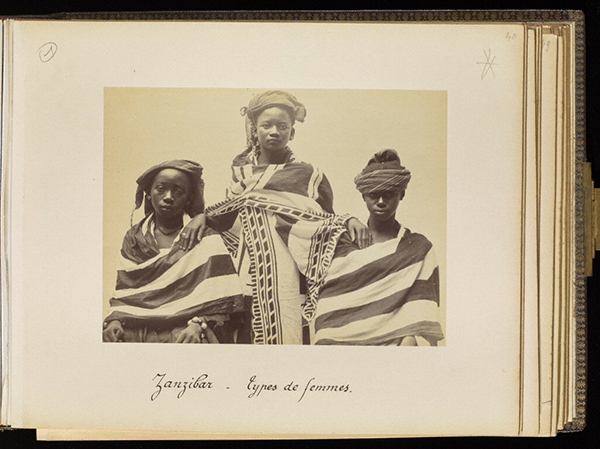

Women from Zanzibar, 1893, Edouard Foà. Albumen print in Views of Africa: Zanzibar et Côte-Quiloa-Dar es Salam-Tanga-Somalis, plate 40. Mount: 9 x 11 1/4 in. The Getty Research Institute, 93.R.114.1.2

From 1886 to 1897 French explorer Edouard Foà worked in Africa, first managing a trading company in the French colony of Dahomey and then exploring East and South Africa, having been invited by the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs to cross the continent from the Indian Ocean to the Atlantic.

During this decade in Africa, Foà took over 500 photographs and purchased others from the few commercial studios operating in coastal cities. Compiled in seven albums with annotations, the photographs document such indigenous people as the Amatongas, Ndebele, Zulus, Khoikhoi, and San (“Bushmen”) and include views in modern-day Nigeria, Benin, Ghana, Togo, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Lesotho, Swaziland, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Malawi. Like the books he published describing his explorations, Foà viewed his photographs as benefitting the disciplines of geography, ethnography, natural history, and science, in addition to promoting commerce, industry, and colonization of the continent.

Foà’s photographs speak to the striking visual and human complexity of African life and colonial engagement in this era. In West Africa he stopped in the Yoruba port city of Lagos (a former Portuguese trading post now part of Nigeria). Here the photograph he took of a trader (“negociant”) and his family underscores how the local subjects and the explorer together shaped the image.

Family of a Merchant, 1886–90, Edouard Foà. Albumen print in Views of Africa: Côte d’Or-Ashantis-Krou-Mandigo-Niger-Salaga-Ténériffe-Madere. Book dimensions (closed): 10 1/4 x 13 3/8 in. The Getty Research Institute, 93.R.114.2

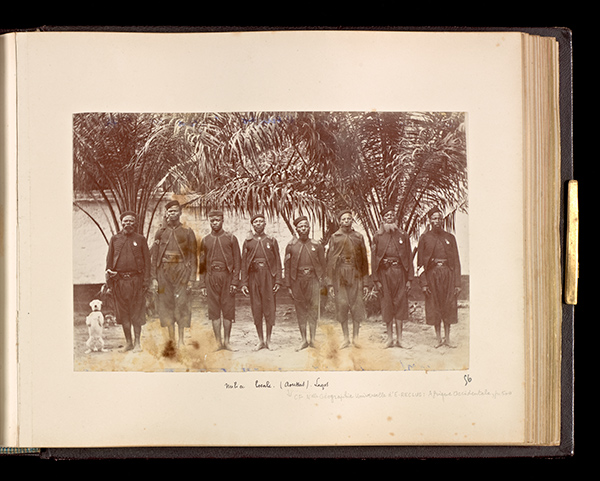

The trader and his senior wife are shown seated in the center of the front row, she on his left in characteristic Yoruba symbolic framing. The young child to his right is likely a daughter; the women behind and to the right could be junior wives or daughters. The merchant’s status, additionally marked by his cane, serves to link him to his European partners. Standing behind the merchant is one of his assistants carrying a circular cow-fur fan, an important symbol of chieftaincy. In Lagos, Foà also photographed a group of local guards wearing uniforms that draw on both European and Middle Eastern traditions. Note on the far left that Foà has included a small white European dog, erectly standing at attention, which may be more than a playful engagement and one, perhaps, shading to mockery.

Lagos Local Militia (Aoussas) of Lagos, 1886–90, Edouard Foà. Albumen print in Views of Africa: Côte d’Or-Ashantis-Krou-Mandigo-Niger-Salaga-Ténériffe-Madere. Book dimensions (closed): 10 1/4 x 13 3/8 in. The Getty Research Institute, 93.R.114.2

In East Africa, Foà found a very different society. In 1888 in Zanzibar, the spice rich island off the eastern coast of what is today Tanzania, the daughter of a local Sultan and his Circassian concubine published the story of her remarkable life. Born as Sayyida Salme (1844–1924), the Zanzibar princess would publish under the name Emily Ruete, the name she had assumed on her marriage to a German merchant who lived in Zanzibar near the palace.

This volume, Memoirs of an Arabian Princess from Zanzibar (reprinted many times) details the rich cosmopolitan court life found there in the period just prior to Edouard Foà’s 1893 visit. This area of co-joined African and Arabic culture became known as the Swahili Coast and extended north to sites such as Kilwa and Mombasa in Kenya, as well as to the neighboring coastal area. Ethnically and religiously rich, the region boasts a diverse population whose traditions originate from Africa, the Arabic peninsula, India, and Europe and a long history of engagement and cross-fertilization, based in large measure on trading textiles, spices, decorative arts, ivory, and humans.

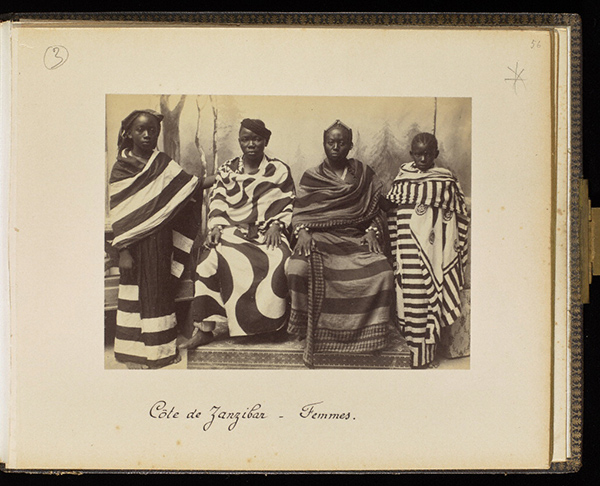

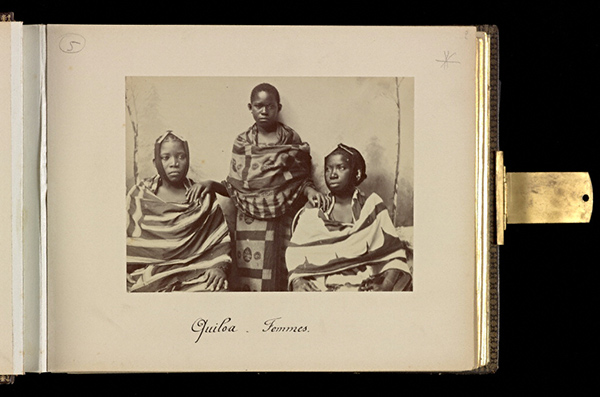

While Zanzibar was heavily influenced by Islamic and Persian contact in this period, it remained into the 19th century one of the main export sites for slaves. The prominence of Africans from inland areas of the continent pictured in Foà’s photographs reveals this legacy. Several images feature women in various poses wearing the distinctively bold patterned regional textiles that became a key marker of elite status. While some of these women may have once been concubines (or daughters thereof), each has chosen to define herself through a very distinctive cloth pattern, one that would have had a specific name and connection to personal events.

Women from Zanzibar, 1893, Edouard Foà. Albumen print in Views of Africa: Zanzibar et Côte-Quiloa-Dar es Salam-Tanga-Somalis, plate 56. Mount: 9 x 11 1/4 in. The Getty Research Institute,

93.R.114.1.4

Women from Zanzibar, 1893, Edouard Foà. Albumen print in Views of Africa: Zanzibar et Côte-Quiloa-Dar es Salam-Tanga-Somalis, plate 45. Mount: 11 3/16 x 9 in. The Getty Research Institute, 93.R.114.1.3

Women from Kilwa, 1893, Edouard Foà. Albumen print in Views of Africa: Zanzibar et Côte-Quiloa-Dar es Salam-Tanga-Somalis, plate 2. Mount: 9 x 11 1/8 in. The Getty Research Institute, 93.R.114.1.1

Kanga, the name of this cloth, derives from the Swahili term for the guinea hen, referencing its bold polka-dot feathering. Originating in the mid-19th century, the textiles’ bold dark-on-light motifs are said to have their origins in printed kerchiefs introduced by the Portuguese that were sewn together to form a cloth. Indian traders living in Zanzibar copied the cloth forms for wider distribution, making them even more popular. Kanga patterns changed with great rapidity since the cloth was popular as both gift and fashionable attire. Often kanga patterns carried specific meanings, each motif (a bird, boat, flower, or animal) being used by the wearer to send a message to others in one’s larger family and circle of friends.

Two of Foà’s seven photographic albums, housed in the Getty Research Institute’s special collections, are featured in the exhibition Connecting Seas: A Visual History of Discoveries and Encounters. They provide insight into Africa in the late 1800s and the explorers who sought to document the vast continent and its varied peoples.

With regard to the photograph “Family of a Merchant, 1886–90” see http://africaphotography.org/media-gallery/detail/25/127

Thank you Jürg Schneider for posting this image. Foa was acquiring his images from various sources including local African studios, among these, perhaps, that of John Parkes Decker. So indeed it is possible that both the Foa album (now at the Getty) and the Museum der Kulturen Basel have a print from the same studio.

probably should be ‘négociant’

Indeed, the French word for trader is négociant with an accent aigu over the e. However, it is hand-written without an accent on the mount around the photograph. —Annelisa / Iris editor