Nancy Yocco in the Drawings Conservation Studio at the Getty Museum

The intriguing exhibition The Secret Life of Drawings—closing this Sunday at the Getty Center—unveils hidden clues to unfinished works on paper, undiscovered sketches, and details of the artist’s craft. It also reveals that making damaged art look presentable can be a perilous undertaking.

Many Old Master drawings, those created in Europe between the 1300s and the 1800s, have been repeatedly handled by artists and collectors, and stored and displayed in poor conditions. Over time, many of these delicate sheets have acquired unsightly blemishes, which distract from their images of kings, gods, heroes, soldiers—or skulls, bugs, and goats.

Enter the conservator, a master make-up artist whose mission is to repair precious images so the focus is on the beauty of the original design, not the damage. There has long been a tension between eliminating distractions and disfigurements such as stains and tears, and taking artistic license, said Nancy Yocco, associate conservator of drawings.

“In conservation, you want to strike a balance so you can let the viewer enjoy the design without the noise of the damage being the overriding visual takeaway,” she said.

Turning off that background noise requires steady hands and a very particular repair kit. On top of ultraviolet light and microscopes, conservators swear by Japanese paper, which has super-strong fiber, and is chemically neutral and easily removed. Paste is handy to mend tears, and glass blocks, weights, and blotters hold the rare pieces in place on the laboratory table.

Sometimes, a gem is revealed in the process—such as the “B-side” of a sketch or a watermark that helps determine the date of the paper. As paper was very expensive before the industrial era, artists often used every inch of it, sketching on both sides.

One of the exhibition’s 30 drawings in need of remedy was a rare 16th-century image of a mercenary soldier by Wolf Huber. The charming drawing was dotted with brown spots, known as “foxing,” caused by mold. Wielding a small brush with an ammonia solution, the conservator gave the piece a makeover without leaving a mark. You can see how Nancy approached its conservation in the video below.

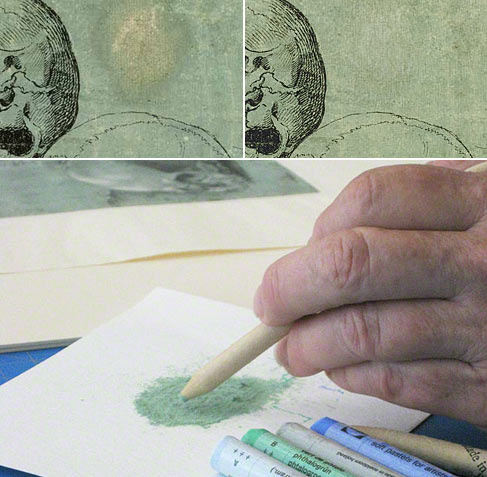

The beautiful Study of Three Skulls had different condition issues. The 500-year-old pen-and-ink drawing on green paper had a disfiguring oil stain adjacent to one of the heads. The fix? A trio of different colors of pastel mixed together and applied to the sheet with a stump, or tool made of soft, rolled-up paper. Employing pastels is tricky, as they can disturb the particles clinging to the paper’s surface.

Working on Study of Three Skulls. At top left, the disfiguring oil stain; at top right, the same area of the sheet after the application of pastel.

Some repair missions are challenging for yet other reasons. Take the case of Maurice-Quentin de La Tour’s 18th-century Portrait of Louis de Silvestre. Some of the original chalk lines containing lead white had changed over time to black, rendering the jovial figure a bit off color. Nancy applied hydrogen peroxide suspended in ether to return the pigment around the nose and collar to its original white pastel.

Portrait of Louis de Silvestre before and after conservation. At left, black discoloration is visible under the sitter's right eye, as well as on the bridge of the nose and the rim of the collar.

What’s interesting—and unusual—about this intervention is that it’s irreversible, and reversibility is one of the conservation profession’s mainstays. Nancy, however, is confident the changes conformed to the artist’s intent. An examination of the chemical compounds proved that the lines were originally white. “I can sleep at night,’’ she said. But, she continued, if a restorer drew, say, a figure on a drawing, that would be an improper impersonation of the artist.

Cue Nicolas Poussin. An 18th-century restoration of Poussin’s Apollo and the Muses on Mount Parnassus is a key example of stepping over the line. A figure of a muse was lost from the drawing during its history, and the space was replaced with antique paper. The restorer boldly redrew a figure, mimicking the artist’s style.

Detail of Apollo and the Muses on Mount Parnassus showing the figure sketched in by a restorer.

Paintings conservators traditionally have more leeway to conform to the artist’s original intent. Reversibility is safely retained with invisible protective layers that are applied between the original and the conserved touches. But drawings on paper don’t have the layers of paint and varnish that would allow for ethical in-painting and protection of the design.

The bottom line is that each drawing is an individual, requiring a tailored approach. Thanks to Nancy and her colleagues, all of the delicate drawings in the Museum’s collection will be safely shielded from excessive handling and environmental assaults for posterity. The artists would no doubt have been pleased to see their work so well cared for in their old age.

I just showed my children (6 and 8) the conservation video…. they were fascinated by the combination of art and science.

That should be “(six and eight)” by the way… no way to edit the smiley after I sent the comment!