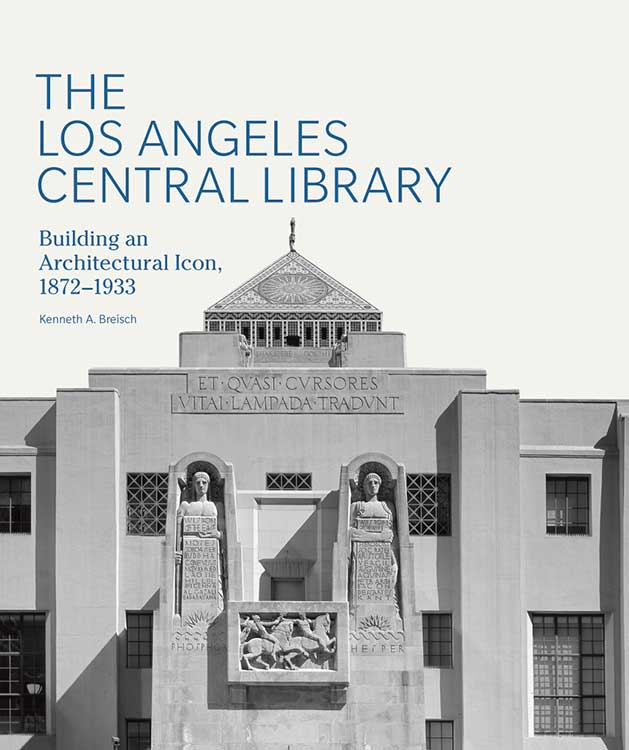

The Central Library in downtown Los Angeles is an iconic architectural landmark with high open ceilings, remarkable murals, and a striking façade. Kenneth Breisch, author of The Los Angeles Central Library: Building an Architectural Icon, 1872–1933, discusses the extensive development of the library over the course of several decades, from its founding as a private library association to the construction and design of the beloved building that still stands today. Breisch is associate professor in the School of Architecture at the University of Southern California.

More to Explore

The Los Angeles Central Library: Building an Architectural Icon, 1872–1933 book information

Los Angeles Central Library library information

Transcript

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

KENNETH BREISCH: I didn’t want to just write a history of the building that Bertram Goodhue designed in the 1920s. I really wanted to look at the whole history of the institution, building towards that moment when they could move into it.

CUNO: In this episode, I speak with Kenneth Breisch, associate professor in the School of Architecture at the University of Southern California, about his recent book titled The Los Angeles Central Library: Building an Architectural Icon.

The Central Library in downtown Los Angeles is a beloved landmark among Angelenos far and wide. If you’ve ever visited it in person or seen photographs of it, you know why. It is an extraordinary structure with domed celestial ceilings, expansive murals, and figurative sculptures that appear to emerge from the architecture itself. The building is the largest public research library west of the Mississippi and it functions as the headquarters for the Los Angeles Public Library system, which serves the largest population of any public library system in the United States.

In his recent book on the Los Angeles Public Library, published by the Getty in June 2016, Kenneth Breisch chronicles the institution’s first six decades, from its founding as a private library association in 1872 through the design, construction, and completion of the iconic Central Library building in 1933. This story reveals the complexities in the development of a civic institution—a public library in particular—alongside a civic plan in a rapidly growing city. The building of a building, we learn, is more than just its materials and design, it’s also its people and politics. I met with Ken one afternoon at the Getty to talk about his book.

I want to begin with the title of the book, Ken, because it turns on the verb “building.” And by turning on the verb “building,” the book’s title seems to tell us that its subject is not only the construction of one of the most handsome public buildings in any US city, but also the political drama behind its construction and the philosophical and aesthetic justification of its iconographic program—that is, what made it look the way it does. So how conscious were you about the significance of the term “building” for the library?

BREISCH: I think I’m very conscious of it from the very beginning; in fact, probably thinking about the idea of building more in terms of building a library.

CUNO: You mean the concept of a library?

BREISCH: [over Cuno] As opposed to—the concept and building a collection.

CUNO: Yeah. Oh, I see.

BREISCH: Which evolved slowly over time in Los Angeles, certainly. But you know, people talk about building a book collection. And so that probably, being a lover of books, was in the back of my mind, to some extent. But then I was—I didn’t want to just write a history of the building that Bertram Goodhue designed in the 1920s. I really wanted to look at the whole history of the institution, building towards that moment when they could move into it, I suppose you could say.

CUNO: Well, let’s get started then. What was the city like in the 1880s, at the beginning of the process of [Breisch: Yeah] the conceiving of a library and the building of a library and the role a library would play in the life of the city. This was about the time the railways come to Los Angeles…

BREISCH: [over Cuno] It is, it is. Yeah. Well, the first—actually, there were some aborted attempts to fund a library earlier, but the—there was a private subscription library that was founded in 1872, when the city actually had a population of just a little less than 6,000 people. But that was related probably to the anticipation of the arrival of the first rail line into Los Angeles, but that was from San Francisco. In the mid 1880s, the first transcontinental railroads across the Southern United States arrive in LA, and the population explodes. First in anticipation of arrival of the railroads, the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe, the Southern Pacific, and then once they arrive, it transforms the city in many ways. And it’s at that point in time, in the late 1880s, as the population is moving towards 100,000 people in, you know, a little more than a decade, that the city decides to build a new city hall. And that was designed to accommodate the public library on the third floor.

CUNO: Okay. That’s the building that Caulkin and Haas designed?

BREISCH: Yes, [Cuno: Yeah] right.

CUNO: I didn’t actually know that building, and this is quite an impressive looking building.

BREISCH: It’s actually a very good example of, you know, Richardsonian Romanesque or Romanesque Revival. And there was quite a bit of that in Southern California. Unfortunately, the earthquakes erased a lot of that if not directly, indirectly, because, you know, they were loadbearing masonry structures and subject to damage in any kind of major earthquake.

CUNO: Does that explain the brief life span of that city hall? Because a new city hall comes just fifty years later or so.

BREISCH: Yeah, probably that. But also just the growing population. Both the city hall and the library in the city hall were probably outmoded within a decade of when they were constructed in 1899 because the population just continued to grow.

CUNO: Well, tell us about the early years of the library itself and about Tessa Kelso.

BREISCH: Well, she was very headstrong, a strong feminist. Hasn’t been given the kind of attention maybe that she deserves, although there have been some articles on her, so I have to give a nod to that. [Cuno: Mm-hm] But she really transformed the library into a modern institution. It had been—

CUNO: [over Breisch] Was she a first-generation Angelino, or did she come to Los Angeles?

BREISCH: She came to Los Angeles, but we don’t know a whole lot about her background, I don’t think. She was an editor and writer, I think. She wasn’t really trained as a librarian. But once she was appointed as librarian, she dove into the profession. She started attending the meetings of the American Library Association and actually caused a rumble there, sort of fighting for women’s rights, when the profession was really being dominated by men, although the vast majority of librarians were women. Typical of the nineteenth century, I guess.

She really helped to transform the library. She and the board convinced the city council, shortly after they moved in, to allocate $10,000 for new books. And that really began to build the collection. Under her watch, also, they eliminated what was a rather modest but an annual dues that patrons had to pay. So it really became fully a public library.

CUNO: How did people access the library at that time? Where did they live in this—what we now think of as Los Angeles, and how did they get into the library? There are these wonderful pictures in the book of all these suited gentlemen sitting at the tables reading these books, reading newspapers and things. Were they coming from their workplace? Were they coming from home?

BREISCH: Well, there were probably two different types of patrons initially, who were shortly joined by children. But the library, you know, historically in the United States, had been sort of schizophrenic. You had the gentlemen’s reading rooms, and they catered really to the business community, sometimes to the working class. But they would be coming from work. And then you had the women readers, who often had their own room, so that they wouldn’t have to mix with the coarser male population, maybe. And that was true at the LA Public Library initially as well. There was a women’s reading room, and then the general reading room. And then very quickly, that was followed with the children’s reading room.

CUNO: You make reference in the book to the role that John Cotton Dana played in the development of the library as a cultural institution. Not the LA Public Library, but [Breisch clears throat] the library as a cultural institution. I only knew of him as a founder of the Newark Museum; and perhaps the two were linked, the museum and the library.

BREISCH: Yeah, I think they were linked when he first arrived in Newark in—

CUNO: New Jersey, yeah.

BREISCH: Yeah, in Newark, New Jersey, exactly. But he was a very influential voice for the library profession, and was really, in the middle 1890s, a great advocate for the democratization of the institution. He advocated for open shelves. Previous to the 1890s, books were kept locked away in their own shelving rooms, their own stack rooms. And librarians had to get the books and bring them to the public. He felt that it was important that the public could browse the shelves. He was also a major advocate for the development of independent children’s departments and children’s reading rooms.

CUNO: And how did those ideas, his ideas, come to Los Angeles? By way of Tessa Kelso and her meetings of the Library Association, with—in Mackinac, Michigan, [Breisch laughs] I remember one such meeting. Seemed like a strange place to go for a great international meeting.

BREISCH: Well, that, and through the Library Journal, which was, you know, published monthly after 1876. Dana also published some books on library management, as well. But he published in the Library Journal and there were a series of sessions at the annual meetings, certainly, of the American Library association, where all of these ideas were [Cuno: Yeah] not only being put forth, but hotly debated. [Cuno: Right] If you can think of librarians [Cuno laughs] as hotly debating open shelves and children’s reading rooms. But there were a lot of librarians who just didn’t feel that the public should be allowed access to their books. [Cuno: Yeah] They felt like the keepers of the treasures.

CUNO: Yeah. So this kind of a library, coming from the ideas of John Cotton Dana embraced by Tessa Kelso and the ambitions of Tessa Kelso, was when the library was, as you mentioned, in City Hall.

BREISCH: Right.

CUNO: When does it leave City Hall and goes into manufacturing buildings and various other kind of commercial spaces?

BREISCH: Well, that’s after 1905, after Charles Lummis arrives. [Cuno: Uh-huh] The board hires Charles Lummis, who was a real strong supporter of Los Angeles at the time, but really had—he was the editor of magazines and a writer, but had no library experience. But they turned to him, hoping that, I think, a male could finally get them out of City Hall and into more appropriate kinds of quarters.

CUNO: And why was it more appropriate to go from City Hall to a commercial building, for example?

BREISCH: I think that was supposed to just be a transitional move.

CUNO: Before the building of a real independent city hall?

BREISCH: [over Cuno] Yeah, they had—they had completely outgrown their quarters in City Hall. They were just on the third floor of, you know, a relatively small building. And the number of patrons and the circulation had grown exponentially under the three women that we’ve been talking about.

CUNO: It would seem like a waste of time—and I kept thinking about that in reading the books—as they were [Breisch: Yeah] moving from one property to another property, as if they had to redo that property, make it into a library. So there’s a cost associated with that, and then you didn’t stay there very long and you had to do it yet again for another space. It seems like someone would’ve said, look, this is a waste of public resources; we can find a better way to do this.

BREISCH: Well, a lot of people did. [he laughs] Especially the board. It was really inefficient to do that. But on the other hand, they had been trying to find funds to built a purpose-built library building, really, since the early 1890s. There had been a number of bond issues presented to the electorate that had failed. And then by the late 1890s, they were turning to Andrew Carnegie, at least in part, to—in the hope that he would be able to fund a new building.

CUNO: Yeah, now, that seems to be—it’s an incredibly important point and a very interesting part of the narrative of your book. And Lummis plays a role this. And is he hired in part because he would be someone they thought could convince Carnegie of supporting the project?

BREISCH: Well, I think first of all, he was hired because he was a male. [he chuckles] And I think the board had run through a number of women, as they saw it, I should say. The women actually were, I think, much more professional, and even familiar, much more familiar with how a library operates than Lummis was. But I think they felt that a male voice could convince the city to allocate money for a new building or could convince either a local patron or Andrew Carnegie to donate money for—

CUNO: [over Breisch] And there was no local patron identified.

BREISCH: No. Actually not.

CUNO: LA didn’t have that culture, the way they have the culture back East, with maybe long generations, multiple generations of patrons or something, who might want to bestow their generosity upon a public library.

BREISCH: Yeah, LA was a very different culture—I think it still is, maybe [he laughs]—than the East Coast at that time in particular where you had, you know, the old families, some of which went back to the original settlement of the colonies who were well respected within the communities. By the middle of the nineteenth century, in some cases even a little earlier, but the Civil War certainly spurred industrialization, and some of those families became the major industrialists in New England or up and down the East Coast.

They, because of their family roots, I think, felt a stronger obligation to return some money to the community. Although it often was self-interested, in that the libraries they built were named for the family [Cuno: Right] and became memorials to their industrial wealth and their family history, in some way. And—

CUNO: [over Breisch] Yeah, so it doesn’t happen in LA, but—

BREISCH: We didn’t have that here.

CUNO: But there was this idea that Mr. Carnegie, who had already announced his program for [Breisch: Right] supporting libraries, and had already begun to support the building of a library in San Francisco or Denver or did that come afterwards?

BREISCH: That came a little bit after that. Carnegie started to build libraries in the communities in and around Pittsburgh, where he had his industrial base, his steel plants. And so he was building libraries for his workers, beginning in the 1880s. But he developed this idea of kind of self-help, that libraries could help raise people by their own bootstraps and educate them. So he began really locally in the 1880s. By the late 1890s, he had spread his largesse nationally, really. And right at the end of the nineteenth century, it was announced that he had given money for a new library building in San Diego, and another in Oakland. [Cuno: Oh] And I think with San Diego, that really [Cuno: Yeah, sure] tipped the balance because although LA had far outstripped San Diego by that time in population, they were still rivals [Cuno: Yeah] because San Diego had the great port that LA never had [Cuno: Yeah, yeah] until they built one artificially.

CUNO: Yeah.

BREISCH: So there was a rivalry there, and so they said, well, if Carnegie can give money to San Diego, why can’t he give money to us for a new building?

CUNO: And their idea was that he would give money for the central library.

BREISCH: For a central library and that—

CUNO: [over Breisch] And at some point, he turns from doing that to providing branch libraries, support for branch libraries. And they missed the boat, as it were, on that.

BREISCH: Yeah, they really did. Although also, there were a number of editorials in Los Angeles papers, the Herald and the LA Times, which really presented Carnegie’s gifts in a—in a negative way. Sort of implying that, you know, LA was better than a city that needed to go begging to an eastern industrialist. And we know that James Bertram, Carnegie’s secretary, his personal secretary, had a clipping service. So he knew everything that was being published about Carnegie all across the country. [Cuno chuckles] And I have a feeling that, you know, they were a little bit more disinclined to give money to LA because they were saying not such nice [Cuno: I see] things about Carnegie. [Cuno: Yeah] But you’re right. About the same time as LA really began to look to Andrew Carnegie, he had shifted his focus from building large central libraries to giving money to build branch libraries, and also libraries in small communities all across the country. Ultimately, you know, building more than 1500 libraries in the United States.

CUNO: I thought it was very clever of whoever—I can’t now remember who among the sort of characters that was involved in this—came up with the idea that, well, if we get money from him for branch libraries, we could just enhance one of the branch libraries and make it into a central library. It’d be a cunning way to use his money for purposes he didn’t intend it to be used. [Breisch: Mm-hm] But that didn’t work.

BREISCH: No, it didn’t work. Carnegie eventually did allocate $210,000 to Los Angeles for six branch libraries. And they were all to be equally funded by that money.

CUNO: 30 to 40,000 each or so, yeah.

BREISCH: [over Cuno] Yeah, 30 to 40,000 each, which was exactly what Carnegie envisioned. We still didn’t have a central library at the time, [Cuno: Yeah] which is what we wanted. So the suggestion was made to James Bertram that perhaps one of the buildings could be built for something in the range of $60 or 65,000 and be used as a temporary kind of central library. And they got a very curt answer immediately from Bertram saying, “Take the money as it’s offered to you or not at all.”

CUNO: Yeah, yeah. Alright, so now we’re close to the building of the building itself—that is, to the architecture aspect of the building. This involved a site for the library, which hadn’t yet been determined at the time. It was moving about the City of Los Angeles or the cent—what we now think of downtown Los Angeles. But there were a few sites under discussion, including the site of the normal school, the teachers school, and Central Park, which is now Pershing Park (read: Square). How did the library’s site selection fit in with this City Beautiful plan that was being developed across the country and embraced by the country, and never seemingly embraced fully by Los Angeles?

BREISCH: Well, I think, you know, probably the primary sentiment early on was to place the library in Central Park, now Pershing Square. But there was a lot of resistance to that, as there still is to building institutions in parks. Think the Met in Central Park. You know, people—

CUNO: [over Breisch] The fight in Chicago.

BREISCH: [chuckles] Yeah. You know, people wanna preserve open space. And even back in the early part of the twentieth century, that still was a very strong sentiment. So there was a debate as to whether the library might be placed there or they might find another location for it. At the same time, there was an embrace of the City Beautiful movement in Los Angeles. And there were a whole series of schemes to build centralized civic centers, but also cultural centers, or perhaps combining both. This was something that happened in Cleveland, in Denver, in particular, Pasadena, with its civic center a little bit later, as part of the City Beautiful movement. And so there were a number of schemes set forth for this idea. And one of the main focal points for an ensemble of buildings was what was called Normal Hill where the state normal school was located, the forerunner of UCLA, actually, because of its sort of raised location, its prominent location. And—

CUNO: At the sort of base of Bunker Hill, or the down side of Bunker Hill.

BREISCH: It’s—yeah, it’s sort of the lower southern or southwestern edge of Bunker Hill, which then rose up kind of precipitously above that. There were proposals to put everything up on top of Bunker Hill, as well, at one point. All of them probably too grandiose for what LA could afford or accomplish at the time. And that really held up, you know, the building of a new central library, because it got caught up in all of those kinds of politics.

CUNO: Yeah. There were two important people at this time that you write about, Everett Robbins Perry being one of them, and Orra Monette being another. Tell us about those two.

BREISCH: Well, Perry was an interesting individual, certainly. He had been trained as a librarian and had worked in St. Louis for a short period of time, and then moved to New York and worked for the New York Public Library. He was young and ambitious. In 1911, LA was looking for a new librarian, and he applied, and got a lot of support, I guess. Came out and was offered the job almost immediately. Probably because of his association with the New York Public Library which had just completed their great new central building on 42nd Street but also had built some sixty branch libraries using Carnegie money. Perry arrived in 1911, just when Carnegie had offered the $210,000 to Los Angeles. And so I think the board felt, well, here’s our man, he can actually get these branch libraries built. He brought a great deal of professionalism to the job. But again, they were looking for a male, [Cuno: Right, right, right. Yeah] I think, at this time.

CUNO: He seemed to have a great ally in this Orra Monette, who was a board chairman or something.

BREISCH: [over Cuno] Yeah, they seemed to really bond. It’s hard to find—well, I think there is more information out there on Mr. Monette. But he had come from Ohio. He was a banker and a lawyer. He was very well-connected in the community, and apparently was quite charismatic and was able to convince the city council to, you know, move forward with new ideas for the library.

CUNO: Yeah, and I gather on June 7th, 1921, funding for the library is finally approved by the— [Breisch: Right] by the city council. And that was forty-nine years after the Library Association itself was started, so [Breisch: Right] that was a long trajectory of [Breisch laughs] attempts, and success and failing along the way. Is that typical of public institutions?

BREISCH: [over Cuno] No, I think it may hold the Guinness Book of Records for [he chuckles] a large central library actually being accomplished. Cleveland had a great deal of trouble, as well. You know, it was always difficult to raise a lot of money. But LA in particular couldn’t convince Carnegie to donate the money; they didn’t have a local philanthropist; and they couldn’t convince the electorate to pass a bond issue to build the library. In part, in the teens, that was because they were in competition with the growth of the city which needed water. So the Owens Valley aqueduct was being constructed. Actually a little bit earlier, but completed in the teens. And they were beginning, just after the nineteenth century, even a little bit earlier, with that, too, to build the harbor. [Cuno: Yeah] And the city was expanding exponentially and annexing huge swaths of land.

That meant that they needed to build a new infrastructure of roads, of electrical connections, water mains, sewer mains. They were all competing with the library, which fell, you know, down the list because they needed the necessities first.

CUNO: And I guess there was the First World War and the kind of anxieties about the First World War, yeah.

BREISCH: [over Cuno] That got in the way, as well. It, in a way, got in the way. There was a bond issue. It looked like it was gonna be placed before the electorate, just before the war. And at the last minute, the mayor said, “No, nothing until after the war is over. This is where we’re focusing our attention.” Actually, Everett Perry got very involved in supplying books to army bases or military bases in Southern California. And the library really jumped into the war effort. They collected books, they collected money—books in particular—that they crated up and sent overseas or to other military bases. And that got quite a lot of attention. So in a way, the war stalled, you know, the building of a new central library; but I think the passage of the bond issue in 1921 was premised on a lot of the good will that was raised by the efforts of the library to support the war.

CUNO: Yeah. So it’s 1921. A good decade for building great, big public ventures, because there seemed to be a lot of money in the twenties, until the end of the twenties. But nevertheless, that was 1921. And there was a guy, Perry, and there was Monette on the board, so there was a team that was there, able to sort of pull of this great big venture. The first thing they had to do—and they had a site. [Breisch: Mm-hm] So the first thing they had to do after that was to get an architect. [Breisch: Right] So how’d they get the architect?

BREISCH: [he chuckles] That’s still a little bit of a mystery. There was a lot of discussion about whether or not the board could just hire an architect. But the city attorney said that they really needed to hold a competition. That would be the only fair way to do it. Everybody who entered the competition was local except for Bertram Goodhue. Goodhue kind of came out of nowhere, although he would’ve known about the competition, probably through his formal colleague Carleton Winslow, Sr. who had worked with Goodhue on the construction of the Panama-California Exposition in San Diego in 1915.

CUNO: [over Breisch] Yeah, tell us about that, because that was extremely influential in the selection of Goodhue, I think.

BREISCH: Well, the exposition itself was envisioned to celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal. And San Diego, being the closest American port to the Panama Canal, felt that this held great fortune for their economic future, so they wanted to celebrate this. They initially were working with Irving Gill, a local architect, but then decided that they needed somebody more prominent; but also seemed to have decided that Gill’s work was a little too modernist and austere for an exposition, which should be more theatrical and ornate as opposed to the type of things that Gill was designing at the time. So they turned to Bertram Goodhue.

CUNO: Now, Goodhue was identified with a kind of integrative approach where he integrated sculpture with architecture and then ultimately it would be mosaic and painting, too. Was that part of his initial plan, and was he chosen to do that, to design a building that was going to include the sculpture and mosaics and paintings, as well as the architecture?

BREISCH: Well, it would’ve included a sculptural program of some sort in the Spanish sort of Baroque tradition, or Spanish Colonial Revival tradition. The sculptor hadn’t been chosen, but Goodhue certainly would have insisted that his long-time colleague, Lee Oskar Lawrie, be chosen as the sculptor for the building. But in terms of how it was originally envisioned, it probably would’ve been more—a more traditional kind of Baroque sculptural program, with statues of various figures placed on and around the building. But at the same time, Lee Lawrie and Goodhue were developing, really evolving, a new type of form in Nebraska.

CUNO: Yeah, right.

BREISCH: Which had really won him the competition in Nebraska. And this really revolved around an integration of architecture and sculpture, so that the sculpture, as it does in Los Angeles, appears to grow sort of organically out of the architectural forms.

CUNO: [over Breisch] Yeah, it’s not just attached to the architecture, yeah.

BREISCH: [over Cuno] As opposed to attached. And Lawrie talks a great deal about that, how important that was to both him and Goodhue that the architecture and the sculpture be one, essentially. Lawrie and Goodhue actually had been working together since the late nineteenth century. And Lawrie carved a lot of the sculpture, or designed a lot of the sculpture, for Goodhue’s Gothic Revival churches. So they had a long and close partnership.

CUNO: By the time we get to the LA Central [Breisch: Yeah] Library building, that Neo-Gothic style has become a kind of almost expressionist style or even an Art Deco kind of style, in which there’s a kind of crispness to the design, a kind of rectilinear crispness to it. Is this something that Lawrie’s work evolved into over the course of the design of the building, or did it start that way with the—

BREISCH: Well, I think you’d have to say both Goodhue and Lawrie, because by this date, they were working very closely together. If you look at some of the drawings in the book, you’ll see that the sculptural program is very vague. There are just sort of generalized sculptural figures in Goodhue’s drawings. And Lawrie actually, at one point, says that Goodhue had come to trust him so much that he would call him over to his office—they were both in New York. Goodhue would call Lawrie to his office, point at the drawings, point to the places where sculpture was needed, and say, “Here’s where we need sculpture; you know what to do.”

CUNO: Right, yeah.

BREISCH: So he wasn’t even designing the sculpture. So he trusted Lawrie implicitly to develop this.

CUNO: And Lawrie produced—I mean, the library is famous for its sculpture, he was producing maquettes, which were then carved onsite. And there was one celebrated incident, in which the carving didn’t quite meet the expectations of either the architect or the sculptor. What kind of talent was local in Los Angeles for the kind of sophisticated carving that the building represented?

BREISCH: Not much. There was not much local talent. They actually imported several sculptors from New York who then worked with local sculptors as well to produce the sculpture. But you’re right, Lawrie would produce one-third scale plaster maquettes in New York. They would be shipped to Los Angeles, hoisted up onto the scaffolding, where then the sculptors would take measurements from the maquettes and carve in situ. It’s a really interesting process that I don’t think has really been given any attention previously, or much attention, in that the building itself is reinforced concrete construction. But as the concrete was being poured, they embedded limestone blocks into the concrete, and then the sculpture was carved, as you say, in situ, in place, which is a very Medieval kind of idea that really wasn’t being used elsewhere in the United States, as far as I know, at all.

CUNO: But did they work together on the program for the sculpture in the building?

BREISCH: No. Actually, that’s an interesting story in itself, because the general program, which revolved around this notion of the light of learning, was proposed by Bertram Goodhue in a letter that he wrote to a Nebraska philosopher down at the University of Nebraska named Hartley Burr Alexander. Goodhue had come to know Alexander through the community for the Nebraska State Capitol building. Goodhue and Lawrie had been developing a complex iconographic program for that building. The state legislature, I think, maybe didn’t trust them because the were Easterners, but also weren’t really satisfied with the program, so they imposed Hartley Burr Alexander on Goodhue and Lawrie, to complete was is a really interesting program in Nebraska. Apparently—I mean, it’s very clear—Alexander and Goodhue really hit it off. They were really widely read and had a kind of romantic streak, I think, about history and mythology that they apparently shared, although there isn’t a lot of correspondence that survives between them to that particular point.

But to get back to the story, Goodhue wrote a three-page letter to Alexander just before the final designs were completed and before Goodhue died, outlining a generalized idea for the iconographic program. But he was going to leave it to Alexander to develop completely. He sent Alexander copies of all of the final drawings, but the inscriptions weren’t complete. They were just generalized inscriptions that he wanted Alexander to complete. And in fact, he told him how many letters he could fit in a particular [Cuno: Yeah] surface, or on a particular surface.

CUNO: So Goodhue was aware of the kind of visual aspect of the sculptural program and the generalized content of it, if not the particularized aspects of it.

BREISCH: Yeah, there were some things that he kind of sketched in, but most of it not. So that all of the Classical figures—you know, Herodotus, Virgil, Copernicus—those all came out of the mind of Hartley Burr Alexander completely. He had actually developed a pretty complete iconographic program, just as the final designs were being completed and being presented to the board in Los Angeles early in 1924.

The board actually approved the whole iconographic program. Goodhue obviously, although it’s not implicitly stated, was very happy with it. Goodhue went back to New York and died of a massive heart attack. And then really, Alexander and Lee Lawrie took over.

CUNO: Oh, right. Was a building underway at that point, 1924?

BREISCH: No, it would be months before even they started excavating the building.

CUNO: [over Breisch] Oh, wow. So who oversaw the building of it and the execution of the designs and—

BREISCH: [over Cuno] Carleton Winslow, Sr. oversaw that, as well as the Goodhue Associates. Actually, just after Goodhue died, there was a bit of a turmoil because the drawings had been approved, but Goodhue was no longer with us. And so there was a question placed by the city attorney, as to whether or not they needed to look for a new architect, because now the architect was gone. And the city attorney ruled that if his successor firm, Goodhue’s successor firm, which initially was called Goodhue Associates, would follow very closely the wishes of Goodhue, and if Carleton Winslow, Sr., who had worked with him, also would make sure that the final design didn’t veer very far from Goodhue’s conception, that they could go forward with that.

CUNO: So he gets the commission in 1921. He works on the design of the building for three years. He dies in 1924. The building begins construction shortly thereafter. And it’s under construction until it’s deemed completed in 1933. So he did not see any of it rising from the ground, as we said. Are you surprised by the sort of quality of the coherence of the design and execution, that it was executed without the architect seeing any of it developing?

BREISCH: [over Cuno] That’s a really good question. I would say no, [he chuckles] in that I think as I mentioned earlier, Lee Lawrie and Bertram Goodhue had been working since really the 1890s. And I think they were working as one by that time. And I think Goodhue had a real implicit trust in the ideas of Hartley Burr Alexander, which is surprising. And then a former associate of Goodhue’s, Carleton Winslow, Sr., was overseeing, you know, the actual construction of the building. Goodhue Associates kept a close eye on things, as well.

CUNO: So we think of the building in terms of its architecture and its sculpture; we haven’t talked about its mosaic or painting program. Were they determined before Goodhue dies? Or is that all after he dies?

BREISCH: All after. All of the mural programs and—they’re primarily murals, most on canvas—were decided upon after Goodhue died, although the great domed interior, which was painted by Julian Garnsey, was overseen in part by Goodhue Associates, as well as a lot of the other interior ornament and decoration. So they were following, really, sort of Goodhue’s ideas and wishes. And it needs to be remembered that they had been working closely with Goodhue on the Nebraska State Capitol, which also [Cuno: Yeah] has very elaborate ornament and murals. So it all was conceived after Goodhue. But it generally, probably conforms to the ideas that he would’ve approved of.

CUNO: Okay, so we have the building [Breisch: Yeah] at one side, on the downward slope of Bunker Hill. And then over Bunker Hill and beyond is the city hall, a great city hall rising up. [Breisch: Right] And then beyond that is Union Station. [Breisch: Right] So those three things that would be anchors to some kind of civic center development got distributed rather than [Breisch: Mm-hm] concentrated. What is the process that led to that, and why did it not develop a more concentrated sense of a civic plan?

BREISCH: Well, I try to outline that in my book, because it’s never really been closely looked at, which is interesting in itself. But there were a whole series of different plans proposed by numerous individuals for grandiose City Beautiful plans. One that would’ve extended all the way from the current location of the city library all the way beyond Olvera Street, and encompassed the entire Bunker Hill area, which actually eventually was redeveloped, beginning in the 1960s, but not as the way it was envisioned as a kind of Roman Forum in the teens and the twenties. But these included public baths and god knows what else. They go on and on. The library got caught up in that. Eventually, I think the library board just got fed up. Monette just said, “No, we’re just gonna move ahead on our own with the library. We can’t wait for a civic center any longer.”

CUNO: Waited long enough.

BREISCH: Waited long enough. So the library went forward, and then in the later twenties, a more rational kind of plan for a City Beautiful governmental center developed around the current City Hall. And that began to generate then other buildings, the county courthouses, the federal building and other things. The idea was that there would then be a park extending from City Hall all the way up Bunker Hill, to the current location of the department of water and power and a kind of second cultural center, you know, around Disney Hall and the other symphonies up there. Union Station initially was, I think, more closely aligned with City Hall, as part of a City Beautiful movement, but then was lopped off by the freeway. And so it no longer feels like part of that evolution or development. But it was located there primarily because there were already railroad yards along the LA River in that location, so it made good sense. But it ended up to be, you know, fragmented. And you know, LA has long been referred to as the fragmented metropolis, and I guess that’s what we got, in a way. It did result in some truly grand architectural monuments. The public library, of course, City Hall. And the department of water and power is one of the great modernist buildings of the post-World War II era in the United States.

CUNO: Well, you tell the story very well, Ken. Thanks for the book, thanks for letting the Getty be a part of this book. You do remind us that the building of a building is more than the building of a building, that it involves all the decision-making processes and all the economy and politics in the building of it. So we thank you so much for the book, for the time this morning on the podcast.

BREISCH: Well, and I might add that the making of a book involves [he chuckles] many, many people, and it was really wonderful working with the people at the Getty. And they produced a beautiful volume. So thank you.

CUNO: Our theme music comes from “The Dharma at Big Sur,” composed by John Adams for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003. It is licensed with permission from Hendon Music. Look for new episodes of Art and Ideas every other Wednesday. Subscribe on iTunes, Google Play, and SoundCloud or visit getty.edu/podcasts for more resources. Thanks for listening.

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

KENNETH BREISCH: I didn’t want to just write a history of the building that Bertram Goodhue de...

Music Credits

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.