While working in Chandigarh, Le Corbusier also developed projects in Ahmedabad, the former capital of Gujarat, 740 miles southeast of Chandigarh. In the second of a two-part series on modern architecture in India, we hear from B. V. Doshi, Le Corbusier’s “man on the job” for his projects in Ahmedabad. Doshi shares his experiences as a young architect working with Le Corbusier in Paris and recounts various projects he managed in Ahmedabad and Chandigarh.

Le Corbusier and Balkrishna Doshi. Photo courtesy of Balkrishna Doshi.

More to Explore

Art + Ideas: Maristella Casciato – Modern Architecture in India, Part 1

Sangath Doshi’s firm

Transcript

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

B. V. DOSHI: Everybody who came here, they were reborn again here. For that transitory period, they were not themselves. That is why that architecture here is of great significance.

CUNO: In this episode, I speak with B. V. Doshi, architect and close colleague of Le Corbusier, in the second of a two-part series on modern architecture in India.

In the last episode, I spoke with Maristella Casciato, senior curator of architectural collections at the Getty Research Institute, about Le Corbusier’s work in Chandigarh, India. In this episode, I speak with the architect Balkrishna Vithaldas Doshi, known by everyone as Doshi, about his time working with Le Corbusier, first in Le Corbusier’s office in Paris, and then in India, supervising projects in Ahmedabad. At nearly ninety, Doshi now heads an architecture studio called Sangath, which is located off a major road in western Ahmedabad. We met in his office where Doshi’s colleagues were coming in and out, stopping at times to listen to our conversation and joining us for tea.

I started by asking about how he came to work with Le Corbusier.

DOSHI: Well, my life has been full of chances. So I left J.J. [School of Architecture] college from Bombay, which I did three years and left halfway. Went to London for ARE [Architect Registration Examination] exam. And there, I by chance, heard about the CIAM [Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne] Congress in Hoddesdon. That was in 1951. And there, somehow I managed to get into the congress, because I was neither a student nor a registered architect.

But then I met there [German] Samper, who was then—Corbusier was doing Chandigarh. So Semper and I started talking about it, and then I asked him whether I can work with Corbusier. So he said, “You write a letter in handwriting.” So I wrote. And then I got a job there. So it was like stage. You know, I was there as a trainee or assistant or whatever you call it. And so I went there in ’51. I did not know French, neither I knew anything about Corbusier. [laughter]

Neither I was a graduate. [laughter] And so I worked there with him for three and a half, four years.

CUNO: On what projects? On Chandigarh projects?

DOSHI: On the—I worked on the Chandigarh Governor’s Place, toward the last phase. And before that, I worked on the Shodhan Villa, which is very well known.

CUNO: Yeah, here in Ahmedabad.

DOSHI: Yes. Then Villa Sarabhai, and the Mill Owners’ building, which you must see, called ATMA. And then I worked on the Governor’s Palace in Paris.

CUNO: Yeah. And all of these projects you were working on, at this point, in Paris. You weren’t here in India.

DOSHI: [over Cuno] In fact, Corbusier only stayed, yes. So it was my learning. Then I came to Chandigarh, and then I came here to supervise the buildings.

CUNO: We went in Chandigarh yesterday, we were at the Capitol Complex. So we saw the great buildings that were built, but we also saw the space that was left, where the Governor’s Palace was meant to be.

DOSHI: Yes. Yes, that’s—

CUNO: So you worked in Paris on the Governor’s Palace project.

DOSHI: Yes.

CUNO: Were you in Chandigarh at some point working on the buildings as they were being built?

DOSHI: I was appointed, and I went there and spent three weeks with Corbusier, and I worked with him on the Governor’s Palace elevations and what. But I did not like that bureaucracy. So I said, “I don’t want to stay here. I want to go.” So he said, “You go and look at the buildings which you have designed.” So I came here to supervise the buildings and complete the buildings…

CUNO: In Ahmedabad.

DOSHI: …in Ahmedabad. There are four buildings of them. One is the Sarabhai house, other one here was the old Shodhan house, that is the Hutheesing house. Then the Mill Owners’ Building, and the museum.

CUNO: What was the ethos like? What was it like to work in the office of Corbusier in Paris?

DOSHI: Well, it was an international office, and also, Corbusier, at this point of time, was of a different world, you know. He was thinking about the other world, which I don’t think he was talking [about] before.

CUNO: What do you mean by that?

DOSHI: Well, a country with great civilization, country with economic stress, you know, independent, like a mandate to do something new here. Let people know what you can do. So challenges of creating for a post-independent country of a great history. So how does one do that here, and then work out the kind of life that is required here? That’s how he came to idea of the béton brut. So concrete, cement, steel—low technology, but a lot of skill and a lot of talent—you know, engineering and others.

So he had a total freedom to do what he wanted to do. And I think he saw the traditional architecture and he saw those buildings which were without doors and windows, verandas, mostly open spaces—the old historical buildings. And I think it must have got him the idea that here is a place which has beauty, great aesthetics—the clothing, the kind of animals, birds—we live in a complete ecosystem. For us, there is no distinction between an animal or a bird flying into the house and ourselves. It may make the thing dirty, but you love them for what they are. I think that whole connection for him must have affected a great deal. And then the way lifestyles were, very frugal lifestyle.

CUNO: What was it like when Nehru embraced the project? How exciting was it for you as a young architect to know that the—

DOSHI: I had no idea at all. It was excitement only. Because neither I had any background of modern architecture. Because I studied in Bombay for three and a half years. And that was, you know, not a very serious study. So from there, I am landed into London to appear for the ARE examination. So that was the first time I see a country where there is quality schools, libraries, and architecture. And then I jump into Corbusier’s office, where I see [inaudible], Columbian, Chinese, Chilean—all kind of people were there working.

So you found multinational cultural people but who had graduation and an experience. And I was completely raw. But I had a deep-rooted Indian ethos, so my dialogue was about the Indian projects, other projects. I’m looking at it from an Indian understanding of life.

CUNO: And did Corbusier talk with you a lot about that?

DOSHI: Yes. He was with me almost every day, for a couple of hours, sitting with me, drawing on the Mill Owner’s and the Shodhan house and the other buildings. So we talked about life, lifestyle, India, his way of staying in India, how he found India. I think somehow I managed to pick up things, you know, because I was raw. My advantage was that I knew nothing.

CUNO: Can you tell us about the process by which Corbusier was chosen to be the architect for the city planning of Chandigarh?

DOSHI: That was Prime Minister Nehru’s idea, because Punjab was being carved out as a new country with the separation, and therefore, they had to build a new capital. So three or four people from the government office went to London and Europe, and they wanted to find out architects, you know, who can be doing this. And in that interview, they met Maxwell Fry and Jeanneret. And I think they mentioned to them that, “Why don’t you go to Corbusier?”

And initially, Corbusier was reluctant but finally agreed. And that is how then he landed in India. But my feeling is that when he came to India, and before, he had some inclinations about what really India is. For example, like, you know, if you look at Robert Delaunay and others’ paintings, and then you see Rousseau’s paintings. So Delaunay came here to India. His wife— because I met Sonia. And so when they were talking, they said, “We were talking to Rousseau about the [inaudible] [read: Indian wilderness], that how India is.” So he was thinking about the snakes and tigers and wild things and all that. And he says that it was influenced them. But that was really the kind of life that people talked.

I also talked to [Iannis] Xenakis. Xenakis was my very close friend in Corbusier’s office.

CUNO: [over Doshi] The composer Xenakis?

DOSHI: Yes. We became absolutely close.

CUNO: Yeah.

DOSHI: So we stayed in an hotel together before he got married. And I used to stay with him; he came here to stay. So he was the one who spoke English in the office. And an engineer of a very high sensitivity. But then I learned about the Greek and the music and other things. So my exposure there was of a different kind. When you have no idea, you are fresh to interpret your way. And I think when I had no idea about modern architecture—For example, I met [Berthold] Lubetkin. During Corbusier’s time, he did the Highpoint. And then he also did the zoo and whatnot. So I met him because another architect from India had gone to Harvard and he had gone on his way to [inaudible] [read: London, Cambridge], he was from Delhi.

So when I left from here, he told me, “Why don’t you meet Lubetkin?” It was the first time I saw in his office and then with his partner, those high-rise buildings, you know, made for workers, proletariats. So he was really the man talking about something else.

CUNO: But what role did Gautam and Gira Sarabhai play in bringing Corbusier to India?

DOSHI: They were the primary—basic role was to really talk to Kasturbhai Larbi and others to say that why don’t we invite Corbusier here? And so when he came here, Corbusier got four jobs in one day.

CUNO: In Ahmedabad?

DOSHI: Yes.

CUNO: In one day.

DOSHI: Yeah, with the same family.

CUNO: Those were two houses and the Mill Association—Owner’s Association?

DOSHI: [over Cuno] The first was the museum. So the museum was for the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation. The chairman, the president of the corporation was Kasturbhai’s nephew. So he said, “Yes, we will like to have Corbusier do the museum,” called Sanskar Kendra. Only the front part is built, and that is why this Chinese [inaudible] [read: Japanese Juichi] have written you little for the grant for that museum. We have restored that building once about twenty, thirty years ago, now the building is in shambles, absolutely in horrible condition. But it’s one of the most beautiful buildings, because when Rogers came to Corbusier’s office—Ernesto Rogers from Milan—he said, “This is like Leonardo da Vinci’s proportions.” So I used to overhear these things. So then you understand what proportions are, what buildings are.

CUNO: So I know that Corbusier designed three museums that are quite similar, in Chandigarh, Ahmedabad, and in Tokyo—

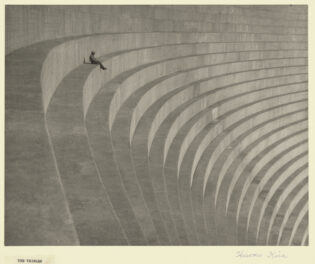

DOSHI: [over Cuno] Chandigarh was the last. The first museum was in Ahmedabad. This growing museum. Only one part is built. Then there was a amphitheater and there was a theater. So I made a Tagore Theater there.

CUNO: Yeah, it’s very beautiful, your theater.

DOSHI: That—the one which is the other side, you know? It’s now mutilated, because it’s not the same from inside. It’s completely changed. But otherwise, that was the building I designed. But Corbusier’s building was there. That is how I came, and I was here for that. Then the same president’s cousin was president of the Mill Owners’ Association. So he says, “I will—we would like to have an office.” And he also wanted to have a house for himself, which was the Surottan Hutheesing house, which—Shodhan’s house.

CUNO: Yeah.

DOSHI: And so that is how he gave him the house, the office, the museum. And then his cousin Sarabhai, she says, “I also want to have one house for myself.” So in one day, Corbusier got all these commissions. And then I wrote an article on it. There I have written how Corbusier of 1929, in his book when he writes about four principles of architecture, the meandering and the cube, and the cube and the white, and the cube which is completely changed. So I wrote on that, of how that was reinterpreted by him in Ahmedabad. And then how it has affected the things, buildings in Chandigarh. So I gave a talk in Chandigarh about this.

CUNO: So the first museum Corbusier built was here in Ahmedabad.

DOSHI: Yes.

CUNO: And then he reprised that design in Chandigarh and Tokyo. What was he thinking of? And what was the basic principle, for him, of a good museum?

DOSHI: Actually, the best thing about the museum here was it was, I think for the first time a what you can call an indigenous but highly sophisticated technology, which was totally sustainable. For example, the cavity lifted the building from the ground. So the air could move through and go to the court. Second, the periphery’s all covered with a cavity wall. So there is an insulation, but there’s a trough, which is now broken. And that trough had creepers, had planted creepers there.

So it was a green box, what we talk today. On top—there is a service floor, and on top was the hydroponics. So you had tomatoes and everything else to be planted there. And this is how that building was conceived.

CUNO: And it was going to catch its own rainwater.

DOSHI: Yes.

CUNO: And that rainwater would then feed the plants, and the plants would grow on the building.

DOSHI: Plants would grow on the building and something will grow on the top, which can be used, you know, as a nourishment to people around. And it was only the light was coming from the skylights. But the service floor was something else which he talked about as a servicing of the museum with lighting and other equipment, et cetera. And eventually, you can put your own air conditioning.

CUNO: We were there just earlier today, and there wasn’t much light coming into the museum. It was quite dark inside. And it seemed to us that the original light scheme that would’ve brought natural light into the building was compromised by recent additions to the building. What was his thought about light?

DOSHI: [over Cuno] I don’t think there is any addition, but the skylight was from the side. And mostly they were elliptical illumination light. And then there is that light where the double light is. And you have a mezzanine floor. So there were the windows which are open.

CUNO: So he was developing his thoughts about how to bring in controlled light, natural light, into the museum. And he was changing his mind from Ahmedabad to Chandigarh.

DOSHI: [over Cuno] I don’t know whether he was thinking or developed or not, because he was always doing things differently. Here, he thought about the hot climate and hot temperature, which was his priority. So I think if one looks at it, that what is the priority that haunts you? Then that is what affects, you know, the design decisions, the main decisions. Like Tokyo has a very different lighting system.

CUNO: And the setting of the museum Ahmedabad within a park, a garden, so you’d have to walk through the garden.

DOSHI: [over Cuno] But it was supposed to be the cultural center of Ahmedabad. It is called Sanskar Kendra Cultural Center, on the riverbank, with a huge area where he had an amphitheater, he had another magic box, that he had workshops, he had a crafts center, and then he had places for people to come and gather. So it was not just a building of one building; it was a complex.

CUNO: But only the museum was built?

DOSHI: Only the first part of the museum was built. [Cuno: Yeah] Even the extensions of anthropology and of science and others, the buildings which were never done.

CUNO: And was the building built with a particular collection in mind? Did the collection precede the building?

DOSHI: There was no collection at that time. And the collection that you see today, the Sarabhai Museum and others, that is a private collection. But the people were involved the same. Actually, the important thing is at that time, Ahmedabad had the leadership almost like the Medicis of Florence.

CUNO: And those were the Sarabhais and the [inaudible]—

DOSHI: No, no, there was Sarabhai, there was Kasturbhai, there were other families. And the city was being managed because, you know, one of them was also the what you call mayor of the city. And the city had this kind of an idea. So it was like the period of Enlightenment. That’s how I was given that job of the IM.

CUNO: IM, the Institute of Management.

DOSHI: [over Cuno] Yeah, I was supposed to be the architect.

CUNO: Instead of Kahn, Louis Kahn.

DOSHI: So I was teaching at Penn. And I said I would like to have Kahn come there and do it and I will assist him. So I became his associate only because I wanted to see that his buildings are realized. And the only way he could come, because I temped him to say that Corbusier is also here. So you come and do the building.

CUNO: So that building is built, that complex is built, the Indian Institute of Management, in the 1970s, correct?

DOSHI: [over Cuno] 1962, we started.

CUNO: You started building in ’2 or designing in ’2?

DOSHI: Designing. Yes, that was the time it was commissioned, and work started maybe ’63, ’64.

CUNO: So the Corbusier projects were just ten years old at that time.

DOSHI: Yes.

CUNO: And when Louis Kahn came, did he spend a lot of time looking at the Corbusier projects?

DOSHI: Yes.

CUNO: And—

DOSHI: I think one doesn’t have to look intensely if you are highly intuitive and talented. So I don’t think, you know, that Kahn had to see so much in detail, like a student. I think the whole idea, that this was a free space. I mean, Mill Owners’ Building is one of the most remarkable buildings, even today, because there are no windows, no doors, nothing. I even did not do the main door.

CUNO: This is the Mill Owners’ Association.

DOSHI: [over Cuno] If you go there, you don’t know where the building is. I mean, a non-building or a building. Sarabhai House is the most important architectural masterpiece because it is non-architectural. Simple walls and a barrel vault. And the façade is completely closed. You don’t even express what is inside.

CUNO: Did the Sarabhai House succeed or precede the Mill Owners—

DOSHI: [over Cuno] Same time.

CUNO: The very same time, yeah? Because they’re very different looking structures.

DOSHI: No, no, no, they were all different, you know, four buildings going on. Jaoul house was going on, and then Ronchamp came. So you can imagine that all these buildings came a little later and after, but during the same time. The whole idea is that, does an architecture has a form which is defined by theory?

CUNO: By theory, yeah.

DOSHI: [over Cuno] Or not. Is it defined by theory or it is convention, or it is something which is rooted in the place? And I think that question is not asked today, even.

CUNO: So you were in charge of Corbusier’s office here in Ahmedabad during those building projects?

DOSHI: Yes.

CUNO: Yeah. How did you communicate with him?

DOSHI: He came twice a year only.

CUNO: How much time, then, did it take for you to send a letter off to Paris, to get an answer back from Corbusier?

DOSHI: Maybe three weeks. Total, three weeks.

CUNO: Were you free to—

DOSHI: [over Cuno] But the work was slow. Yes, yes. I was free, because all the furniture there and the building, Mill Owners’ and others, I designed many things. I was in charge of the building in Paris, so I took a lot of decisions. And the furniture that I designed, he approved.

CUNO: When I see that building, I think of the Carpenter Center in Cambridge. Was that about the same time?

DOSHI: This is before.

CUNO: Mill Owners’ is first. Yeah.

DOSHI: Yes.

CUNO: And it was an idea that this ramp that would proceed up through the building and— up to the building, through it, and down the other side.

DOSHI: [over Cuno] The reason is very simple, that if you’re on the road and the road has a big plateau, and then the river is something like three, five meters down below, you don’t see the river. The only way you can do it is by going up. And then suddenly the whole vista is open.

CUNO: Yeah, yeah.

DOSHI: That was his sketch only. He gave me a file folder like this with that sketch, ramp. And he says, “Now you design.” There was no program.

CUNO: Did you and Jeanneret talk to each other often?

DOSHI: Jeanneret, whenever I went to Chandigarh, I talked to him.

CUNO: But he was working just hours away from you in Chandigarh.

DOSHI: But it was very difficult to reach there unless you go by train.

CUNO: How long did it take?

DOSHI: Over a night, I would go from here to Delhi, and then Delhi to Chandigarh. So five hours from Delhi to Chandigarh.

CUNO: Did you spend a lot of time with Jeanneret in Chandigarh? Was it helpful to you?

DOSHI: I only went there when Corbusier was there.

CUNO: And when he was there, did he always come to Ahmedabad?

DOSHI: No, no. He came only few times.

CUNO: Were you pleased with the quality of craftsmanship on the buildings here at Ahmedabad when you were building them?

DOSHI: Yes, yes, yes.

CUNO: Were they all local craftsmen and local designers and engineers, yeah?

DOSHI: Yes. Absolutely.

CUNO: What—

DOSHI: Actually, the whole thing is very rough. But the wood and other things are detailed, yes. So you can see the contrast.

CUNO: But what about the National Institute of Design?

DOSHI: That is done by Gautam Sarabhai, and he looked after it and he supervised, also, yes.

CUNO: Tell us about Charles and Ray Eames coming to Ahmedabad.

DOSHI: They came around the same time. See, all this is between ’62 and’65.

CUNO: And did they come at the request of the Sarabhai or the government?

DOSHI: [over Cuno] Well, I think the government of India and the Sarabhais for that, but it was government of India. And even IM was not supposed to be Ahmedabad. So that is actually the period when India was talking about setting up institutions.

CUNO: Did you have conversations with the Eameses when they were here and they were talking about the—

DOSHI: [over Cuno] Yes, yes, very well, very much. Because I also met them before. Charles Eames I met before, in Chicago, when I had received the Graham Fellowship. That was in 1958. I got $10,000 to do nothing. [they laugh] Just to spend, to go, whatever you want to do.

CUNO: But when they were here, were they talking with you about the kind of architectural curriculum you thought might be helpful to future architects? Or were they importing to India their own ideas about—

DOSHI: No, I think you must see that suppose you or we go now to Africa or some other island, you know, and do something there. I think we would not think about what we know. I think it’s a chance to discover yourself again. So I think everybody who came here, they were reborn again here. For that transitory period, they were not themselves. That is why that architecture here is of great significance. Because sustainability becomes extremely important, climate becomes very important, lifestyle becomes very important.

And the way—then their behavior is the connection with the place around. And I think that’s how civilizations have happened. So theory and books, you know, are meant, you know, for academic world, where the world is going on in production line. But the other places, that you discover something what is relevant to you with what you have.

CUNO: I think I remember that John Cage and Merce Cunningham and Robert Rauschenberg and David Tudor all came to the National Institutes of Design.

DOSHI: [over Cuno] Yes, they came to Ahmedabad, they came through the Sarabhais. They all came here because it’s a new land, but a land of great culture, great history, great food. So you are creative person, so you design what you want to do and you try and try. Actually, it’s a big relief from going from an overpowering cultural tradition and where theories dominate. But you go here to a place which is open and there is nobody talks about theory. They talk about life. They talk about sustainability. They talk about joy and celebration.

CUNO: Tell us about Louis Kahn and his time in Ahmedabad.

DOSHI: Actually, when Louis Kahn came, very strange, I was teaching there, so he—when I first talked, you know, in Philadelphia in 1960, all the professors, after my talk, we had dinner together, in which Kahn was there also. And [Ian] McHarg was there, Kahn was there, Michel [Richard], was there, Perkins was there. Perkins was the dean. So he did not come, but they all came. And then they were curious about knowing, because McHarg was talking about landscape and Islamic architecture and Islamic landscape. And Kahn wanted to know something about what Corbusier is doing there. So they were very curious. And it was the most exciting period, because they’re asking me questions which I had not thought of. But to me, they were connected. Because I was experiencing what Corbusier was doing here. And [Cuno: inaudible] if you say that you have a building which is non-air conditioned, non-climatalized, and a building, which is open and the wind goes through and the birds go through, where is the theory?

What are we talking of architecture? I mean, this building would not happen unless I was free myself. It was the—this building and these I did, it was the first time I thought that I have now crossed that threshold of what my guru had taught me.

CUNO: And by this building, you mean the building we’re in right now, your offices.

DOSHI: Yes, because the journey itself is like what he would talk about, the meandering route. You know, you come to that. You know, the journey to arrive. And then what you talked about, the light, you get like this light. Look at the kind of quality of light you have. And it changes when the monsoon comes here, clouds—I know clouds from here. I know the day.

CUNO: By the changing of the light.

DOSHI: Yes, and this is also—you can see the way it is. It’s not made in the normal structure, it’s really biological, organic, sustainable building, in which you discover yourself anew every time. And actually, that’s India. India is a place where you become more aware when you cross the road. First time you know that you have to see with your eyes and turn your head. Normally, you would walk through. Change your legs, you know, change your speed. Here, the sounds, you don’t know what is happening for a minute. And I think that’s what this culture is.

CUNO: Did you have these kinds of conversations with Louis Kahn?

DOSHI: Yes, I used to teach in Philadelphia, for twenty-two years, I taught. So every time I would go there I would meet him the day I would arrive from airport, I would meet him, say. And then leave from his office, almost. And most of the time, we would be together in the evenings and afternoons and whatnot, dinners. We became very close family. So I was very privileged.

CUNO: One can’t help but fall under Doshi’s spell. His charm, the twinkle in his eye, his discerning taste, and his role in the history of Indian architecture make him a fascinating interview subject. For the past seventy years he has been at the center of modern architecture in India, creating forms and structures admired for their sensitivity to the needs and character of the local context. It is for this reason that his designs are said to provide one of the most important architectural models for modern India, and, it could be argued, for architecture everywhere.

Our theme music comes from “The Dharma at Big Sur,” composed by John Adams for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003. It is licensed with permission from Hendon Music. Look for new episodes of Art and Ideas every other Wednesday. Subscribe on Apple Podcasts or Google Play Music. For photos, transcripts, and other resources, visit getty.edu/podcasts. Thanks for listening.

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

B. V. DOSHI: Everybody who came here, they were reborn again here. For that transitory period, the...

Music Credits

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.