In September 2017 the Getty launched Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA, a regional exploration of Latin American and Latino art in dialogue with Los Angeles. In a three-part series, we hear about the development of one of the Getty exhibitions that is part of this initiative, Making Art Concrete: Works from Argentina and Brazil in the Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros.

The exhibition is now open! In this final conversation, we meet the curatorial and conservation teams in the galleries to visit the show they’ve been working on for the past several years. We hear from the Getty Conservation Institute’s Tom Learner and Pia Gottschaller, the Getty Research Institute’s Andrew Perchuk and Zanna Gilbert, as well as the University of California, Riverside’s Aleca Le Blanc.

More to Explore

Making Art Concrete: Works from Argentina and Brazil in the Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros exhibition information

Concrete Art in Argentina and Brazil GCI project

Modern Abstract Art in Argentina and Brazil GCI article

Art + Ideas: The Making of an Exhibition, Part 1

Art + Ideas: The Making of an Exhibition, Part 2

Transcript

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

ANDREW PERCHUK: I think what we’re doing here by bringing conservation science and art history together is trying to tell the story of art in a different way.

CUNO: In this episode, I speak with the curators and conservators who worked on the exhibition Making Art Concrete: Works from Argentina and Brazil in the Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros, one of the Getty’s contributions to Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA, Latin American and Latino Art in dialogue with Los Angeles. This is the third part of the series titled The Making of an Exhibition.

Making Art Concrete is an exhibition that has been long in the making. Over three years ago, the Colección Cisernos, founded to support the scholarship and material culture of the Ibero-American world, generously lent forty-seven paintings and sculptures to the Getty for research and study. Our team of scientists and art historians carefully examined the works, combining art historical and scientific analysis to discover more about the material choices and working methods of these avant-garde artists. Their work culminated in an exhibition and accompanying catalogue, both of which were made available to the public this September.

Over a year ago, I began checking in with the exhibition’s curatorial and conservation team to see how their research was progressing, what it was they’d learned, and what they envisioned for the exhibition’s galleries. Today’s episode is the third and final part of The Making of an Exhibition series. The first and second parts of the series, from October and November 2016, are still available if you missed them.

[installation sounds]

That sound that you’re hearing is the actual installation of the exhibition.

The exhibition is now finally up and is a celebrated part of the Getty initiative Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA. PST, as it’s called, is an ambitious exploration of Latin American and Latino art in dialogue with Los Angeles, taking place from September 2017 through January 2018 at more than 70 cultural institutions across Southern California.

Just after the show opened, I met the team in the galleries to look at the results of their work. Tom Learner is head of science and Pia Gottschaller is senior research specialist at the Getty Conservation Institute. Andrew Perchuk is deputy director and Zanna Gilbert is research specialist at the Getty Research Institute. And Aleca Le Blanc is assistant professor of Latin American art at the University of California, Riverside.

If you’ve listened to parts one and two, you’ll recall that the title of the exhibition has changed several times. I started by asking Andrew about the final name they selected for the show.

PERCHUK: The title is Making Art Concrete: Works from Argentina and Brazil in the Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros, which for those of you who’ve been listening from before, is a change from Límites Concretos, which was the title that we had as a working title coming into the exhibition, which had a lovely ring in Spanish that both the limits of Concrete art, but also the concrete as a limit. But really, the exhibition has to be completely bilingual and work just as well in English as it does in Spanish. And the English translation, Concrete Limits, really didn’t work.

CUNO: So it was more a linguistic issue. It wasn’t an intellectual issue that made the change, drove the change.

PERCHUK: But then we came upon Making Art Concrete, which was what we thought both a reference to Concrete art, which is the kind of art in the exhibition; but also to the idea of what the kind of technical analysis, the kind of art history, an exhibition that we’re bringing together, which is to make art concrete. To take something that is sometimes abstract or intellectual and show the material and concrete nature of it.

CUNO: So if my memory’s correct, this is the third title. You mentioned a second title, but there was one even before that one.

PERCHUK: That’s correct. [they laugh] [The] Material [of] Form.

CUNO: [over Perchuk] What was that title? [The] Material [of] Form?

PERCHUK: Yes.

CUNO: I want to give our listeners a chance to understand how you worked on this exhibition, because they may not have listened to the first or second podcast. You’ve had the luxury of having these works of art for some three years. Tom, tell us what is it like to have the luxury to spend three years working with a few paintings?

TOM LEARNER: It was a luxury, Jim, a complete luxury. And it was an extraordinary opportunity where we had both the Getty programs wanting to do this work, So the Conservation Institute, who had done a lot of work understanding how to identify paint and support and how works of art are put together. A huge interest on the GRI’s part, in terms of looking at what that technical information can mean and how it can be used for art historical thinking. A collection that was willing to lend up to almost fifty of its key works for three years, take them off the, you know, exhibition circuit. They were willing to transport the pieces to a facility downtown LA, where we actually did our first podcast.

The one other really important part of this, which I know appealed to all of us curating the show, was the role that the Getty Foundation played, too, who gave grants to two very, very important research centers, both universities, one in Brazil, one in Argentina, the main conservation training programs, with their exceptional analytical and art historical facilities. And they were able, with this money, to do concurrent projects on very similar works of art from similar collections. Some of the major private and institutional collections in both Argentina and Brazil.

So as a package, this was really quite extraordinary.

CUNO: Yeah. You mention the importance of the Cisneros Collection. Aleca, can you tell us why it’s so important?

ALECA LE BLANC: Well, the obvious answer is because Patty Cisneros was one of the very first collectors in the United States who began looking at Latin American abstraction in depth. And quite honestly, the quality of the works are superb. However, I think that’s only piece of what makes this collection so important. She’s been committed from the very beginning to circulating this collection and rather than kind of keeping it in her residence or in storage, lending it to every institution or university that would be interested in showing this work. And it’s basically been on permanent tour since in the 2000s, as many of know, ’cause we’ve all seen this in lots of different places, in lots of different iterations.

And in fact, Tom alluded to this a few minutes ago, but borrowing this many works for three years made me feel a little bit guilty, quite honestly, because I knew I was kind of taking them off the market for other curators to include in their exhibitions. But, you know, I think her kind of unflagging support for circulating this work, making it available to as many students and scholars and researchers, through exhibitions and publications, and sponsoring professorships and seminars and events and all sorts of different things, has really—you know, this collection, she has kind of singlehandedly shifted the narrative of Latin America art as it’s taught in the United States.

CUNO: Prior to the work that she did in amassing this collection and sponsoring the kind of research that you’ve undertaken on the collection, what did we in the North America think of the art of Latin America?

LE BLANC: It was about Mexican muralism, and by extension, Frida Kahlo. And that was largely what people thought of in the United States when there was any mention of Latin American art. And I actually remember my very first time of meeting Patty in 1996. She said she was starting an anti-Frida Kahlo organization, precisely—not for any reason against Frida Kahlo’s work—but precisely to try and make people aware that it was a much larger—you know, there’s a much larger landscape of artwork being made across Latin America. It’s a huge region, obviously. Mexico is even part of North America. This doesn’t even touch on South America. I’ve been thrilled to kind of watch it happen and see how successful she’s been.

CUNO: Yeah. Patty and her husband Gustavo are from Caracas, Venezuela, [Le Blanc: Mm-hm] although they live now in New York. And of course, they had examples in Venezuela of the kind of art that they would then collect, and must’ve influenced them to think of Latin American art very differently than it had been thought of before. What were those examples?

LE BLANC: Primarily, I would say the work of Jesús Soto was most important. He was from Venezuela. He lived in Paris in the fifties, and he made some of the earliest kind of abstract compositions that also had kind of an optical effect to them. And from that, some of his other colleagues who came from Europe and worked there, they began kind of looking at certain kind of kinetic and optically, you know, reverberations in works of art that were completely abstract and divorced from any kind of reality. And I think from that, that there was a very kind of logical kind of extension to Concrete movements in other parts of Latin America.

CUNO: I know that one of the important things that you have studied in the course of this exhibition is the relationship between the materials of the works of art and the industry, and the politics associated with the industry, of the cities from which the works were painted or made. And you’re concentrated on Buenos Aires and São Paulo and Rio. But the collection began in Caracas, Venezuela.

LE BLANC: Yeah.

CUNO: And you just described some of the artists and identified some of the artists, [Le Blanc: Mm-hm] who worked on it. Why were they not included in the exhibition?

LE BLANC: Well, it’s an interesting question. And how we even came to this collection to begin with was not through the lens of an exhibition, but through the approach of a research project. We were interested in kind of the ramifications of industrialization across Latin America.

And so in the very earliest iterations, we were interested in Venezuela. We were also interested in Mexico, considering how these kind of industrial movements played out postwar. And then through, you know, a very careful kind of process of research—I mean, we knew we couldn’t do four countries. I mean, that was a ridiculously large research project. It would’ve had to be divvied up into more than one kind of iteration. And so we really carefully and intentionally narrowed it down to Brazil and Argentina for a number of reasons. And from a very pragmatic perspective, the political situation in Venezuela right now makes it impossible to actually go there and do any research.

CUNO: Now, you’ve described the work in the show as Concrete art. We’ve talked about this in parts one and two of this podcast, but let’s just close the loop in this episode. Zanna, tell us again why it’s referred to as Concrete art?

GILBERT: Well, I think maybe it’s important to say that the loop can probably never be closed on, you know, what Concretism is or means in different places at different times. But for Argentina and then later, Brazil, they’re sort of taking up the idea of Concrete art, which was coined in 1930 by Theo van Doesburg. He was Dutch, but he was active in Parisian abstract circles. And so then artists in Argentina, postwar, sort of took up this idea of Concrete art once again, which would be an art that focused on its materiality, on surfaces. And we kind of understand it as a form of geometric abstraction, but in fact, those artists didn’t like to be considered abstract because they were creating not images that were abstracted from reality, but actually concrete images, which were to be a kind of reality unto themselves. When we talk about the concrete, we’re talking about a sort of real material entity.

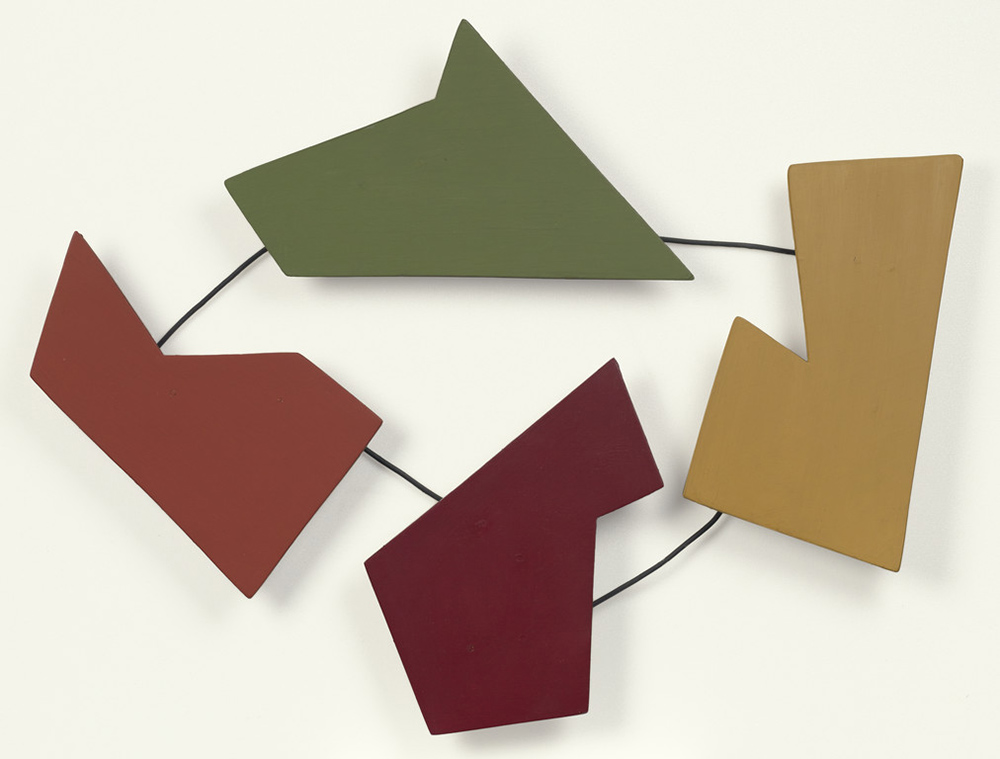

CUNO: What work of art here in this gallery might best illustrate that?

GILBERT: This is a work by Raúl Lozza, from 1946, called Relief No. 30. It’s a series of four independent planes. There’re four elements, which are differently colored—green, yellow, a sort of dark burgundy, and a brick-like red—that are joined together by a piece of wire. And so there’s no surface support for these works; they’re intended to sort of be floating on the wall and supported just by a wire. And Lozza paid very, very careful attention to the surface of the work, the paint that he was using, and he carefully polished, to create exactly the kind of matte surface that he was able to achieve.

PERCHUK: And I think one of the ways that the Lozza that Zanna was talking about really defines the Concrete is that if you have a canvas and you are making brushstrokes on it, to some degree, whatever forms you’re making are representations on a shape. In the case of Lozza’s, these are objects that inhabit your space. They are real things, not representations of things on a support. And when he calls them coplanar, they are physically on the same plane. Meaning that the wire that connects—

CUNO: [over Perchuk] And they’re parallel to the wall.

PERCHUK: And parallel to the wall, exactly.

CUNO: Tom and Pia, you’ve spent just as much time looking at these works of art and examining them through scientific analyses and your own auricular analysis. And to come up to some conclusions about how they were made and how they’ve aged over the course of time. And that kind of knowledge conjoined with that art historical knowledge that we’ve just heard described, the paintings, how did that change for you over the course of time that you’ve been dealing with these? And have you learned things you didn’t know about them, didn’t anticipate about the paintings? Did it change your view of them over the course of time?

PIA GOTTSCHALLER: Well, I would say I didn’t really have a lot of preconceptions about what we would find. I had seen the collection or parts of the collection once or twice earlier, in some of the exhibitions Aleca mentioned. So I had some vague idea of what to expect, in terms of construction. But then I think whenever you have this incredible luxury of studying something in great depth and over a long period of time, I think that’s where the three years come in. [she chuckles] The beautiful thing about that is that you start out with a number of questions, very simple, like how is it made? What did the artist uses? Perhaps why did the artist choose something specific over something else? But then as you keep going, other questions come up. And then in this particular case because we have had them for such a long time, you can go back and then, for example, take another sample, if that’s what’s necessary for answering your question. Or you can think of a different way of maybe finding a solution to a problem, with the help of a colleague who is a specialist in something else.

So I think that’s the special thing about this project, that we’ve been able to start out by answering very basic questions, and then being able to drill down for each single work, and maybe sometimes also see that an artist wasn’t necessarily always doing the same thing on every work, even though it’s from the same period, but maybe tried out different things on different works.

CUNO: Yeah. I think it’s one of the things that probably surprises visitors to exhibitions, when they come and they see works of art, they think they’ve always looked the way they look now. But your study must have found that things looked differently, and over the course of some fifty to sixty years that they’ve been in the world, they’ve changed over the course of time. Are there examples of that?

LEARNER: There are examples of that. It’s actually very, very hard to answer that. And I think probably one of the most common discussions we had amongst ourselves was just that. How much has this changed since it came out of the artist’s studio? And the sort things we know are happening, it’s just very hard to know to what degree. But paints often become discolored, they become more transparent. You see the whole time in lighter colors, and white paints in particular. Looking around the galleries, we have whites that that appear very yellow and somewhat discolored. But the sort of normal way of looking at a work of art and trying to estimate how much it’s changed is when you have a painting in a frame and the frame’s protected behind the frame rebate from the light, and you have an immediate comparison. Of course, none of these works of art are framed at all, so it’s really hard to precisely say exactly what shade of white or how opaque a painting would have been. But changes have actually happened. And it does impact on your perception.

I think the other change that’s undoubtedly happened is on some of these solid supports, which would’ve been very kind of flat and completely parallel to the wall. Some of the largest square pieces have definitely warped a little bit. It’s just a natural consequence of these materials, especially when they’re being exposed to climates and aren’t kept completely flat and stable. That said, these works of art are getting quite old now in terms of modern and contemporary art, and they’re in amazing condition, most of them.

CUNO: I would imagine if the visitor to the exhibition things that the works of art have always looked the way they look now, artists might have thought that they would always look the way they looked when they were first painted. And especially in the concept of “the modern” and “the contemporary” and “the concrete,” in which these things are made of new and modern materials. Do we have evidence of artists being unhappy with the way things have changed, and wishing to go back in and restore them to an earlier stage?

LEARNER: I’ll let someone else answer that specific question, but I would just answer with a very general comment on that, Jim, ’cause it’s actually a constant area of interest, when you start to look at the conservation aspect of modern and contemporary art. I think with very contemporary artists, when artists are still alive, it’s very, very typical—not always, but very typical—that an artist has a huge amount of influence in how a work of art not only looks, but how it changes or not. There’s often an enormous pressure to keep things looking exactly as they were when they were created. Sometimes it’s just impossible. Things do age. Everything ages, and sometimes the concept an artist is trying to portray is so important that almost the materiality gets pushed way down the list of importance. When you go back through the twentieth century—and I’m going to arbitrarily pick a figure of about fifty years back; this is a completely kind of random number—but it seems to be when you go back beyond fifty years, that pressure becomes much less important, much less apparent, and the historic value, the actual material value, there’s a much more interest in understanding what you’re looking at is the original material that has then aged. And I think with this group of work, we’re just beyond that fifty year boundary, so I think in general, now, we haven’t had much discussion at all about trying to recreate some of the differences that would’ve been in the past.

But Pia, I mean, the only two artists that are still alive in this exhibition are Judith Lauand and Maldonado. And do we have any correspondence with them about how they feel about the works now?

GOTTSCHALLER: I don’t think—well, I know for certain that I didn’t ask Maldonado that specific question, because he felt that all of this was done so long ago, when he was in his early twenties. And he probably also hasn’t seen some of them for a while. But the one artist I can think of who has talked about seeing his works age, and grappling with the changes in color specifically, is an artist who’s not represented in this exhibition, but was an important member of the Argentine group. And he was called Martin Blaszko. At one point, he made sculptures that he painted white. And he used a house paint, which is tendentially yellowing more quickly or more strongly, depending on the formulation, than other paints would. And he, in the eighties, really disliked how aged they looked. And he also owned a work which we studied as part of this project by another artist called [Gregorio] Vardanega. And he at one point felt that the background had yellowed to a degree that wasn’t acceptable. And he decided to repaint the background with a whiter white. But then the interesting thing is that when a Swiss dealer, Miklos von Bartha, came to Argentina in the late eighties, early nineties, who bought a lot of the works that we also see here in this exhibition, he had conversations with all of the artists about the aging of their works and what great value lies in the original surface. And a number of them had then said in later interviews, how much this conversation changed their thinking about what, you know, aging is and how, as they themselves get older, they’ve developed a different relationship to aging. So I think it’s very often that, you know, your relationship to the aging of an artwork also reflects your relationship with your own aging.

CUNO: Yeah, yeah. Well, I’m sure that’s true. In my case, very true. So as a team, you represent different perspectives on the subject, art historians and conservation scientists or conservators. And the exhibition is about both the art history and the making of these objects that comprise the exhibition. How do you hope the visitor will access the kind of information that you’re revealing from this exhibition?

GOTTSCHALLER: I’ll maybe give you the first answer from a technical point of view, and then my colleagues can talk about the other aspects. I think that we feel a beautiful takeaway for our visitor would be if they, through the information that we show them—whether it’s cross-sections that we’ve taken that allow people to, as it were, look into the artwork, or details that highlight a particular aspect, such as a surface that was manipulated in a certain way, or details that show our visitors subtle but important differences in how edges and lines were painted—that they come away with a sense of having been able to appreciate the very many steps that were involved in making each artwork, and how perhaps the information that we show them encouraged them to spend time looking at things that might have escaped their attention at first.

CUNO: Do you think that kind of scientific aspect of things takes away some of the mystery of the work of art?

GOTTSCHALLER: I actually think it often increases the mystery, because if you break down a very magical piece of art into its components, and then you go back to the, you know, greater sum that it really constitutes, I think people are amazed what you can do with really mundane materials. So I would actually personally hope that our visitors feel that they’ve—you know, that they’ve been rewarded in spending time in looking closely, because a lot of these works look like they could’ve been done very quickly, you know, sort of by myself. That, you know, that sort of attitude, I think we would love to dispel. And we can, if people are willing to spend just a little bit more time.

CUNO: What about the art historians, from your point of view how do you hope that the visitor will access the work that you’ve done?

LE BLANC: In very much the same as Pia. I want them to look closely. I think a lot of times, and I think frequently with geometric abstraction, people come into a gallery and kind of immediately register, oh, I get that; those are shapes and colors, and oh, this is a square, and kind of move quickly. And what I’m hoping, you know, with the information on the wall, in the kind of the didactic corners, but also just the restraint and the editing, in terms of how many works are in the gallery, that people will be encouraged to slow down. And there is huge rewards for close looking. You know, many of these works are painted not just on their surface, but also on their sides. And that’s not something you can get by zipping past it.

CUNO: Yeah. Andrew.

PERCHUK: I think that one of the things we wanted to be is provide information without hitting the viewer over the head. And one of the things that we set up the exhibition, is if you’re not interested in the didactic material, if you’re not interested in the science and how these were made, you can experience this exhibition purely as an art exhibition. It functions as a show of Concrete or geometric abstraction beautifully. But it’s there if you want it. And one of the many things, as both Pia and Aleca have talked about, is a lot of people have no sense of the thought and effort that goes into making what seem like relatively simple shapes. But when you see, for instance, that one of the geometric works here was made first by putting a pin in and creating the edges of the shape; then taking a needle and incising that into the canvas or the shape; then taking a draftsman’s tool, a ruling pen, and filling in the incised line; then masking it off and painting it, you really see the extraordinary level of skill and craftsmanship and forethought that goes into making what seem on the surface maybe to be relatively simple shapes.

CUNO: We have three galleries. Each gallery, I suppose, represents a different aspect to the exhibition. Could you describe how the exhibition is laid out, one gallery to the next?

GILBERT: So we’re standing in the first gallery. And this room deals with the construction of the works and the ways in which artists in both Argentina and Brazil broke with the convention of the frame. So we have shaped paintings; paintings that bring the frame into the composition of the work; coplanars, as we discussed before, with elements parallel to the wall; and other works that protrude into the space of the viewer. So the first room is sort of organized around that concept of how artists constructed their work and how they departed from the conventions of painting. And then the second room—Pia, do you want to give the tour of the second room?

GOTTSCHALLER: The second room focuses on two subjects, paints and the kinds of surfaces you can create with different kinds of media. And one of the things that I think we mentioned in an earlier podcast is that we found this amazing variety of different paints. And different paints, whether they’re oil paints or house paints, they allow you really different surfaces. And the second subject is the different tools and methodologies that artists sort of adapted, partially invented, for creating these very sharply-delineated geometric forms.

GILBERT: And the third room. And the third room of the exhibition is mainly drawn from the Getty Research Institute’s special collections. It focuses on interdisciplinarity in the Concrete art movement. So you know, part of the project of this exhibition was to look at the artists as makers, the ways in which they went about making their work, and situating that within the broader art historical context. And so this room deals with them in a broader context, in terms of artists who worked with poetry, with design, and with other forms of interdisciplinary arts.

CUNO: And we know from projects that you guys have worked on together before—that being the Pollock project in particular—that this is the kind of exhibition the public likes very, very much, for the reasons already described—the close looking, the technical aspects, the demystifying, the mystifying of various things related to works of art. So we know it’s gonna be very crowded, so we should encourage people to come early and often, to see the exhibition. But I want to give you one last chance, each of you or any of you, to think about the exhibition and what your ambitions were when you started and how you feel now that it’s just about to open.

Tom?

LEARNER: I had, well, many ambitions, but maybe two I can point to very quickly. One was just this very kind of scientific, technical part of it. You know, could we take our existing ways of doing our investigations on paintings that have come out of Europe and North America and apply them directly to this region and get the results we did? And that was fantastic, so we achieved that very, very clearly. And then more specifically about the exhibition, it really is the struggle to get the information across in a clear and effective way. And I know that sounds very, very straightforward, and I think for myself, it’s always a learning curve. And it seems to me, it comes down to making huge numbers of cuts.

I mean, you just—you leave out so much stuff you think is essential for everybody in the world to come see. And you have to make these painful cuts. And with five voices round the table, we have to compromise sometimes. But actually, when we were hanging it last week, I think there was a real buzz, but I think we felt we had an amazing collection. The pieces are spaced beautifully. The big worry that the kind of didactic corners might impose a bit too much, I think we all feel happy; it’s all right. I’m hugely excited.

CUNO: Andrew?

PERCHUK: I think what we’re doing here, by bringing conservation science and art history together, is trying to tell the story of art in a different way. And that people can see because we’ve grouped things in a way that they’re not usually put together, because we’ve put things together by artists using certain kinds of materials or the idea of moving from two to three dimensions, rather than chronology or geography, which is usually how these things are presented. So I think that’s allowed us to do something different. And what I hope is that that also leads to people thinking more broadly about how art history could be different.

CUNO: Yeah. Well, I’ve had the great pleasure of being in your company these past three years, as you’ve been looking at and thinking about these things. And I can tell you that the results are fantastic. The exhibition is beautiful, deeply informative, and it will be exciting to all who come. So thank you very much, all of you.

Making Art Concrete is on view at the Getty Center through February 11, 2018. To learn about Pacific Standard Time and the exhibitions and events happening at more than 70 cultural institutions throughout Southern California, visit pacificstandardtime.org.

Our theme music comes from “The Dharma at Big Sur,” composed by John Adams for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003. It is licensed with permission from Hendon Music. Look for new episodes of Art and Ideas every other Wednesday. Subscribe on Apple Podcasts or Google Play Music. For photos, transcripts, and other resources, visit getty.edu/podcasts. Thanks for listening.

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

ANDREW PERCHUK: I think what we’re doing here by bringing conservation science and art history...

Music Credits

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.