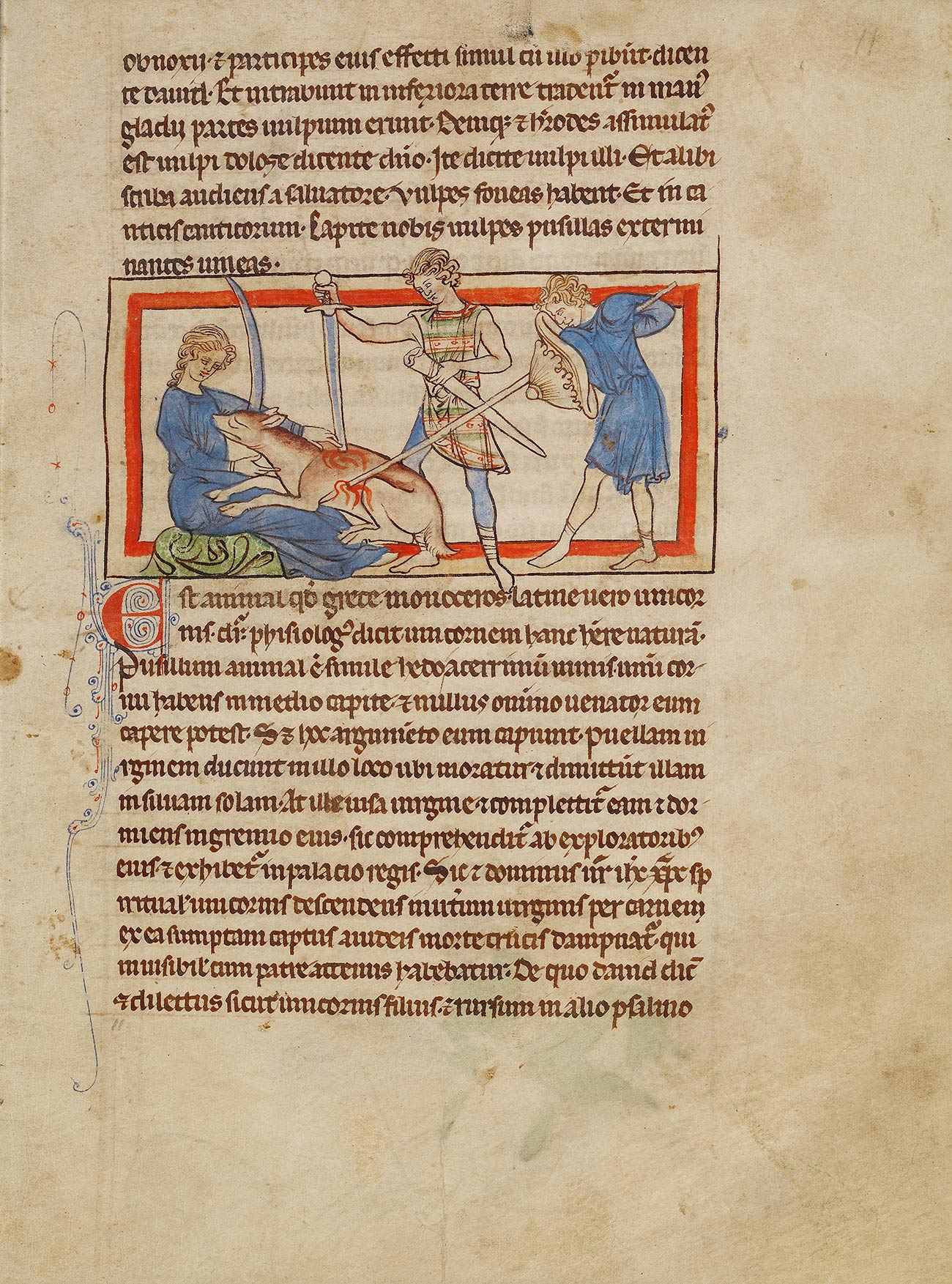

A Unicorn (detail) in the Northumberland Bestiary, about 1250–60, unknown illuminator, made in England. Pen-and-ink drawing tinted with with body color and translucent washes on parchment, 8 1/4 × 6 3/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 100, fol. 11. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Meet 19 animals of the medieval bestiary in Book of Beasts, a blog series created by art history students at UCLA with guidance from professor Meredith Cohen and curator Larisa Grollemond. The posts complement the exhibition Book of Beasts at the Getty Center from May 14 to August 18, 2019. —Ed

With a mighty horn on a donkey’s stout body, the unicorn is an oddity in the pages of illuminated bestiaries. Today we know the unicorn as an imaginary animal and a coy and playful emoji. In the Middle Ages, however, the unicorn had a tragic tale—one quite unlike its light-hearted smartphone counterpart.

Bestiaries were illuminated manuscripts that combined stories of real and imagined animals, using them as allegories for Christian morals. Part theological and part pseudo-zoological, they were designed to reinforce faith in Christian doctrines in the Middle Ages in Europe.

In the bestiary, the unicorn’s story is an allegory for Christ’s death. As with Christ’s crucifixion for mankind’s sins, the unicorn is caught and killed. One bestiary (Bodleian Library, Bodley 764) details the unicorn’s story and follows it with the Psalm 92:10; “My horn shalt thou exalt like the horn of an unicorn.”

Victim of Man’s Violence

The unicorn is commonly described as ferocious; for example, it is said to be an opponent of the elephant, which it would spear in the abdomen with its horn. It is also quick, even impossible to catch. The unicorn becomes docile, however, in the hands of a virgin—symbolic of the mother of Christ, the Virgin Mary.

In many bestiary representations, a virgin is used to lure the unicorn. She heads to the forest until a unicorn sees her and jumps into her lap. Some representations of this moment involve the unicorn sucking on the virgin’s breast until it falls asleep. During its slumber, the unicorn is caught by hunters and ultimately taken to the king.

The unicorn was treasured for its horn, which was thought to have the ability to detect poison if placed in contaminated food or drink, and render it impotent. The horn was also believed to function as an aphrodisiac or teeth whitener when ground into a powder. (Real narwhal horns were usually used as imposters for unicorn horns.)

In bestiary illuminations, the unicorn is almost always shown as the victim of a momentous hunting scene. It is pierced in the side of the lower abdomen by a hunter, while scarlet blood falls from its wounds, recalling Christ’s sacrifice. The virgin stands next to the unicorn, embraces it, or holds it in her lap, often appearing remorseful for having colluded in the animal’s capture.

Unicorn (detail) in a bestiary, about 1250, unknown illuminator, made in England. Pigment on parchment, 30.8 x 23.2 cm. The British Library, Harley 4751, fol. 6v. Digital image: British Library

To emphasize to the unicorn’s fierceness, the hunters in some bestiaries are shown clothed in metal garb from head to toe, with a shield to avoid any damage from the unicorn’s horn.

Today we no longer believe in the unicorn’s existence, and we need not worry about protecting ourselves with armor from its mighty horn. But knowing the unicorn’s story of fierceness, trickery, and bloodshed might make us second-guess using its digital doppelgänger again.

A Unicorn in the Northumberland Bestiary, about 1250–60, unknown illuminator, made in England. Pen-and-ink drawing tinted with with body color and translucent washes on parchment, 8 1/4 × 6 3/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 100, fol. 11. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Text of this post © Christal Perez. All rights reserved.

See all posts in this series »

Cool. Is there any information on where these manuscripts were made? Unicorns of this kind remind me of chapter 23 in the Book of Matthew. It is also a bit ironic that the elephant would be seen as an enemy to the unicorn. The elephant is an animal totem which symbolizes ancient wisdom with good purpose not evil. “Narwhal’ . Who wouldnt be interested in something with a name like this. Mr. Narwhal frequents the chilled H2O of Cananda, Russia, and Greenland. It is an area of Ruough necks of the seas : ). King Babar is not an enemy children; unless , of course, you rather a chaotic confusion filled dysfunctional way of being as opposed to an ordely life. Any hoot thanks I will add this to my Medieval registry from my courses at Stanford.