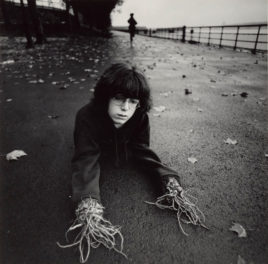

Partition 31, 2015, Christiane Feser. Pigment print, cut, folded, and layered, 55 1/4 × 39 1/2 in. Collection of Trish and Jan de Bont. © Christiane Feser

Within a world of digital photography, the artists in the exhibition Cut! Paper Play in Contemporary Photography have turned to paper as a source of inspiration. All appreciate the physicality of paper, and each brings his or her own sense of wonder, precision, and playfulness to its transformation into something more complex.

In these brief slices of conversation, excerpted from interviews I conducted for the audio tour that accompanies the exhibition, they share what they love about working with paper.

Christiane Feser

Christiane Feser makes photographs of paper she has folded. Then she makes photographs of those photographs, and so on, until it becomes impossible to distinguish the photograph from the photographed.

Christiane Feser: I got more interested in the piece of paper you can touch because digital images don’t alter or age with time. They cannot be torn, they cannot be bent, they cannot be cut, so they are kind of a distant. I’m more interested now in dealing with the materiality and really touching this thing. There’s a German word, begreifen. This word means understand, but to touch something means to understand it.

Laura Hubber: How do you want your photographs to be received by the viewer?

Christiane Feser: When I was still shooting flat, normal photographs, I was always kind of disappointed when I saw how fast people were looking at these works. They look at them and after a few seconds they decide, “Okay, it’s a house, it’s a street,” next picture.

But if you really look closely at something, you get lost in the picture. It is important that people are a little bit like detectives, trying to find out, “What is the thing? What is the representation?” and this is very satisfying for me to see. But I am most happy if they can’t find out in the end all the secrets that are in this.

Hear more from Feser about her relationship with paper in the audio stop below.

(piano music with a sense of uncertainty)

Female narrator: Christiane Feser’s photographs are like visual puzzles that invite the viewer to try to solve them. What is the photograph? What is the shadow? Each invites the viewer to look and look some more.

Christiane Feser: I was thinking about how photography could be more complicated. I wanted to have an image that’s not so much related to the outer world anymore, so I started with paper constructions that I photographed. Then I took this print of the photograph and cut it up again. And then I re-photographed this second construction. And then I print it out again and returned to the first step, so it’s a photograph of a photograph of a photograph and this direct relationship got lost so people could no longer find an easy answer on this question. What is this photograph showing?

Female narrator: Feser began making images this way when she became frustrated by how people consume images.

(music ends)

Christiane Feser: When I was still shooting flat, normal photographs, I was always kind of disappointed when I saw how fast people were looking at these works, and after a few seconds, they decide to continue with the next picture.

Female narrator: She was also tired of experiencing images through the distance of screens and displays and smartphones.

(music resumes)

Christiane Feser: I got more interested in the piece of paper because, digital images, they don’t alter or age with time. They cannot be torn, they cannot be bent, they cannot be cut, so they are kind of distant. I’m more interested now in dealing with the materiality. There’s a German word, “begreifen”: to touch something means to understand it.

We tend to take the photograph for the thing itself. It is important that people are a little bit like detectives to try to find out, “What is the thing? What is the representation?” They spend often a very long time in front of the pieces and they start to talk and they go closer and far away and they look from the side and they speak with each other about what it is, and so this is very satisfying for me to see. But I am most happy if they can’t find out in the end all the secrets that are in this.

(music ends)

Matt Lipps

Models, 2016, from the series Looking Through Pictures, Matt Lipps. Pigment print, 72 × 54 in. Promised Gift of Sharyn and Bruce Charnas to the J. Paul Getty Museum. © Matt Lipps

Matt Lipps began cutting out photographs from Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar and pasting them onto cardboard when he was in high school.

Matt Lipps: That I’m still here twenty years later making paper doll cutouts is a crazy, fortunate thing.

Laura Hubber: Why do you love paper?

Matt Lipps: It doesn’t go away. You can always keep it and hold on to it. Digital pictures get deleted and they are just gone. They go back into the World Wide Web, wherever they go. There is something about that piece of paper that you can rely on, that will be with you, that you need to take care of. Especially if you think about an actual photograph, which has a surface that will expand and contract with heat and moisture, and needs to be protected from light. You need to care for it, like a body almost. The nurturing of that sort of appeals to me.

Paper also crumbles, is torn. I like the wear and tear and wrinkles that happen at the corners of the cutouts when they fall over and get bent. I appreciate the history that is embedded in that object. I’m left cold with a digital image.

Hear Matt Lipps say more about his cutouts:

Female narrator: Artist Matt Lipps has been collecting images since high school. Some of them he saved in binders. Others he cut out and stood up on cardboard stands.

Matt Lipps: That I am still here twenty years later making paper doll cutouts is a crazy, fortunate thing.

(piano music evoking technology)

This picture is from the book called The Great Photographers. It goes through about 30 different photographers and profiles the greats. Each one of those cutouts represents a different idea of what a great photographer looks like, or how they practice. They’re all standing up on these glass shelves and then behind that is a poster print from my own personal archive of negatives from my high school and undergrad.

Female narrator: Even though his photographs aren’t digitally manipulated, Lipps says his practice is informed by the world of technology that encourages quick looking.

(music ends)

Matt Lipps: We absorb images so quickly we think that we know them, but it’s when you really slow down, really examine what’s happening in the foreground, the background and it all starts to come together. I think being an active viewer, it’s something that’s kind of lost in the digital swiping. Swipe left, swipe right.

When I sit at my desk with my cutting mat and my x-acto blade and I’m really sort of tracing the contours and peeling apart the foreground, background, or whatever it is that I’m doing to get to the object, I’m seeing it for the first time in such a different way, a very slow, analog way, where I discover things constantly.

Female narrator: Lipps says his work is inspired by collage, but is more flexible.

Matt Lipps: I have thousands of cutouts in boxes in my studio. I like the idea that I can remix these parts up and I could make a new picture out of it, if I ever wanted to.

Female narrator: For Lipps, paper is an integral part of his photographic process.

(music resumes)

Matt Lipps: Paper doesn’t go away. You can always keep it and hold onto it. Digital pictures get deleted and they are just gone. There is something about that piece of paper you can rely on that will be with you. You need to care for it, like a body almost. The nurturing of that, sort of appeals to me. I actually like the wear and tear and wrinkles that happen at the corners of the cutouts when they fall over and they get bent. I appreciate the history that is embedded in that object.

(music ends)

Thomas Demand

Thomas Demand is a sculptor who makes large models of cardboard and paper and then photographs them. After he takes the photograph, he discards the model itself.

Thomas Demand: I decided at some point that I wanted to be able to make sculpture[s], but not live with them. A cheap material, which wouldn’t bind me financially and space-wise, is paper and cardboard, which is also quite good because everybody knows it very well. The cup of coffee, the dollar note, maybe the newspaper. People have a feeling for paper.

The artificiality of the paper is important to me. It’s a different way to render the world, and it’s nearly as good as the real one. This “nearly as good,” this little gap between what you see there looks a little bit artificial, but is obviously a plant, makes you hopefully think about what we see, and how we see, and how we recognize, and how we communicate about what we recognize.

Hear Thomas Demand discuss his process and his work Landscape:

Thomas Demand: Trust your eyes, and try to figure out how it’s made.

(ambient enigmatic music)

If you look at it long enough you just realize that it’s actually nothing else than a cardboard model. It’s just a stand-in. It stands for our idea of reality.

My name is Thomas Demand, and I am a sculptor, predominantly. I make life-size models of cardboard and paper, which I then photograph, and after the photograph is done, I discard the model itself.

(music ends)

I wanted to make sculptures which are cheap and don’t get into my way. As an artist, you always have a space problem, especially when you do sculptures. I decided at some point that I want to be able to make sculptures, but not live with them.

Female narrator: Demand also likes the way paper is a common medium.

Thomas Demand: Everybody knows it very well. The cup of coffee, the dollar note, maybe the newspaper.

Female narrator: In his photographs, however, the paper almost becomes invisible as it masquerades as what it represents.

Thomas Demand: Landscape is basically the greenery, the cactuses you see when you go up the street. This is actually at the entrance hall of a UCLA building. I always liked the fact that it’s just so banal, but also it’s so beautiful and so complex.

My work is much about filling the frame. Usually, if you make a photograph of your uncle, you also photograph the fence behind him, the sky, the bird which happens to fly through so you get so much more than you actually focus on. My work, I always try to control everything on the picture. Much more like a painter does, because a painter has to paint every corner of his canvas. I don’t have anything coincidental on the photograph. Everything you look at is intentional and is done to be looked at by the viewer, and that kind of connects me a little bit more to a painter in the painting tradition than a photographer.

(ambient enigmatic music)

The artificiality of the paper is important to me. It is a different way of rendering the world and it’s nearly as good as the real one. This little gap between what you see there looks a little bit artificial but is obviously a plant, makes you hopefully think about what we’ll see and how we see and how we recognize and how we communicate about what we recognize.

Soo Kim

Midnight Reykjavík #5, negatives 2005; prints 2007, Soo Kim. Chromogenic print, 39 3/8 × 39 3/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2009.36. © Soo Kim

Soo Kim’s photographs are an exercise of subtraction. She layers two photographs she has made, and takes away volume with a knife to create a more subjective portrait of what she has photographed.

Soo Kim: When I make a piece like the Reykjavik series, it’s showing me a picture of Reykjavik, but I’m subtracting parts of the picture plane away in order to make a depiction of Reykjavik that I’m interested in seeing.

They look less like buildings, less like houses, less like architecture, and more like sketches or an idea of a house, or an idea of a built environment, an idea of a city, rather than what you might picture as Reykjavik or a capital city of the world.

My practice comes from collage; it’s just a subtractive method rather than an additive method. It’s something that the viewer doesn’t see, but in a way, is just as meaningful and important to the photograph itself as what remains intact.

I am interested in the objecthood of photography. There is a certain kind of materiality, a certain kind of objecthood that is in the work. It comes from the paper itself.

Soo Kim talks more about her process and the Reykyavik series:

(ambient enigmatic music)

Female narrator: Soo Kim’s photographs are as much about what she has cut out of them as what they depict.

Soo Kim: I would define my work as photographs that I cut into to remove parts of the picture plane in order to reinterpret the photographic image and change the reading of the photograph itself.

Female narrator: In her series Midnight Reykjavik, she pictured the northern capital city during the summer solstice. Each piece in the series is made up of two photographs that she has cut into and layered.

(music ends)

Soo Kim: They become almost like drawings on the landscape rather than the kind of houses full of volume and space in the way that we would understand an urban panorama, less like buildings, less like houses, less like architecture, and more like sketches or an idea of a house, or an idea of a city.

Female narrator: In these personal portraits of the city, glimpses of the photograph underneath peep out: the sea, or a green spray of bushes. To Kim, a straight photograph is almost too full.

Soo Kim: One of the things that I love about photography is that it’s so generous. It just gives so much information. It’s almost too much information for me to understand. When I make a piece like the Reykyavik series, it is a real photograph and it’s a truthful document of what Reykjavik looked like, but I’m subtracting parts of the picture plane away in order to make a depiction of Reykjavik that I’m interested in seeing, that’s informed by, for example, ’60s architects who were exploring ideas of the Utopic City. I was trying to kind of picture a different version of what I might understand as a picture of a capital city.

(music resumes)

People tend to look at photographs very quickly, and I think we might have the idea that we understand how to read photographs. And so, I think that I try to make photographs that you have to kind of take pause to understand what is happening.

(music ends)

Daniel Gordon

Clementines, 2011, Daniel Gordon. Chromogenic print, 29 3/4 × 37 1/2 in. Collection of Allison Bryant Crowell. Image courtesy Daniel Gordon and M+B Gallery, Los Angeles. © Daniel Gordon

Artist Daniel Gordon makes still lifes from photographs he’s printed on his inkjet printer and crumpled into balls and other shapes.

Daniel Gordon: I was interested in making a hybrid digital/analog image based on a traditional still life. The clementines are made of crumpled up pieces of paper with photographs of clementines glued on top of balls. The materials that I’m using to make these photographs are glue, paper and scissors.

I’m interested in inkjet printing, and the mistakes a printer could make when one color is jammed, and I get streaky lines, or there’s an ink splotch, or certain technical issues come up. I try to embrace those imperfections as a way to signal the tools that I’m using.

My training is as a photographer, but there’s a sculptural element, a collage element, a photographic element, and then more and more a painterly element that has come into my photographs.

Daniel Gordon discusses his photograph Clementines:

(ambient music evoking wonder)

Female narrator: As they cut, layer, fold, and shape paper in different ways, the artists in this exhibition explore how paper can be transformed into something more complex. Each artist brings his or her own sense of wonder, precision and playfulness that is an essential part of the photograph and a medium in and of itself.

In this vibrant still life, the three-dimensional clementines that artist Daniel Gordon has printed in his studio almost roll off the table.

(music ends)

Daniel Gordon: The inspiration was a bowl of clementines…in real life… I was interested in making a hybrid digital/analog image based on a traditional still life. The clementines are made of just crumpled up pieces of paper with photographs of clementines glued on top of those balls. Generally, the materials that I’m using are glue, paper and scissors to make these photographs, and film, of course.

My training is as a photographer. But I was always interested in other mediums, painting, sculpture, even design. There’s a sculptural element, a collage element, a photographic element, and then more and more a painterly element that has come into my photographs.

Female narrator: After photographing his sculptures, he scans the negatives, and creates prints that introduce imperfections.

Daniel Gordon: I’m more interested in photographs that live on paper. I’m interested in the mistakes that a printer could make when one color is jammed, and I get streaky lines, or there’s an ink splotch, or certain technical issues come up. I try to embrace those imperfections as a way to signal the tools that I’m using.

(music resumes)

I think it always comes back to the idea of transformation. There is a kind of magic that happens when you snap the shutter, and the photograph is something entirely different than what was in front of the lens. That’s true for every photograph always. There’s just something kind of magical about it.

(music ends)

Christopher Russell

Explosion #31, 2014, Christopher Russell. Pigment print and Plexiglas, 39 × 57 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Gift of The Mark & Hilarie Moore Collection in memory of the Orlando shooting victims of 6/12/2016, 2016.84. © Christopher Russell

Christopher Russell often cuts into his photographs. Sometimes, he uses a meat cleaver to hack at an image; in Explosion, he uses a razor blade to delicately carve into the surface of the photographic paper.

Christopher Russell: I think beauty is a lure. I’m interested in subversion and if you can sort of infiltrate, find a way into somebody’s space, then they’re more likely to understand what you have to say. So, I think beauty is sort of the hook that gets people in to think more about other issues in the work.

Laura Hubber: What’s your relationship between paper and the photographic process?

Christopher Russell: I mean, if we’re doing it SAT style, “Paper is to photo what spirituality is to daily life.” I mean, you’re releasing this bright white from within. It’s like ghost pictures of the visions of Mary with the glowing heart. That’s kind of what paper is to me.

Christopher Russell says more about his series Budget Decadence:

Female narrator: Artist Christopher Russell says his work is about dark places, but he is careful not to repel the viewer.

Christopher Russell: I think beauty is a lure. I’m interested in subversion, and if you can sort of infiltrate, find a way into somebody’s space, then they’re more likely to understand what you have to say. So, I think beauty is sort of the hook that gets people in to think more about other issues in the work.

(poignant piano music)

This image was from the house that I lived in when I was in L.A. I made five copies of that image and tried to manipulate each one differently. That house, it was the saddest place in the world.

Female narrator: Russell says the owner’s son had lived his whole life in this room.

(music ends)

Christopher Russell: I was only the second person to live there. When I got it, the walls hadn’t been painted. They were dyed plaster and had never been touched and there were marks on the wall, where his wall hangings had been. The child’s bed that he lived in, into his 40s, and so there were just these ghost imprints of his life.

Female narrator: In one of the images, Russell hacks into the image with a butcher knife.

Christopher Russell: It’s just this violent release on the physical space of the home. It gets this sort of bright light, illuminating from the interior of the photo.

Female narrator: In another image, he delicately scratches into the image creating the illusion of wallpaper on the walls and an intricately patterned rug on the floor.

Christopher Russell: The one with the wallpaper is definitely more about sort of wanting something better.

Female narrator: For Russell, paper is paramount to his practice.

Christopher Russell: If we’re doing it SAT style, “paper is to photo what spirituality is to daily life.” I mean, you’re releasing this bright white from within. It’s like those pictures of the visions of Mary with the glowing heart. I mean, that’s kind of what paper is to me.

Comments on this post are now closed.