Heraldry is a fascinating and complex system by which coats of arms are devised and decoded. My familial arms—yes, my family has a coat of arms, and yours may have too—are composed of an intricate grouping of objects, including a horse, a salmon, lizards, and the cross of Calvary, among others.

(In heraldic language, the Keene family coat of arms is described as follows: Azure on a fess per pale gule and argent between in chief out-of the horns of a crescent, a dexter hand couped at the wrist and apumée, surmounted by an estoile, between on the dexter a horse counter-saliant and on the sinister a lion ramp, each also surmounted by an estoile; and in base a salmon naiant all argent; on the dexter side three lizards passant bend sinisterways gule; and on the sinister an oak tree eradicated vert; over all an escutcheon argent charged with a cross Calvary on three grieces purpure.)

Understanding how to decipher a set of arms is at times useful in identifying the individual(s) responsible for commissioning a particular work of art. Let’s take a look at a few objects in the exhibition Florence at the Dawn of the Renaissance to see what we can glean from the presence, or absence, of coats of arms.

The Virgin and Child Surrounded by Saints, between 1350 and 1365, Follower of Bernardo Daddi (possibly Pietro Nelli). Tempera and gold leaf on panel, 37 ½ x 26 in. (95.3 x 66 cm). Portland Art Museum, 61.51

A triptych by a follower of Bernardo Daddi (possibly Pietro Nelli), on loan from the Portland Art Museum, bears two coats of arms along the base. The Aldobrandini arms, on the right side, were identified in 1949 by an Austrian heraldry specialist, who at the time was unable to locate a match for the arms at left. The Aldobrandini crest comprises the following elements in heraldic terms: azure, a bend counter-embattled pointed stars in bend three and three or (basically, a blue background with a line crenellated on both sides like the walls of a medieval castle, with three gold stars on either side).

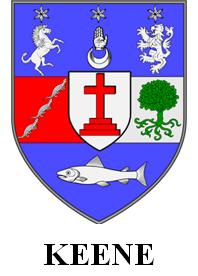

When writing the catalogue entry for the Aldobrandini Triptych, I was determined to find a match for the missing set of arms on the left side of the base. After days researching Florentine families connected with the Aldobrandini, I stumbled upon an exact match for the arms in an online database available containing heraldry for 8,000 Tuscan families. The Ceramelli Papiani, as this resource from the Archivio di Stato in Florence is called, led me to the Coppini family, whose arms contain an escutcheon of azure, with a rose in chief position above a golden chalice, accompanied on either side by a gold pointed star (see the two sets of arms from the Ceramelli Papiani below). Thus, the painting formerly known as the Aldobrandini Triptych can now more accurately be called the Coppini-Aldobrandini Triptych, since the arms of the Coppini family are in the position of authority at left.

The Virgin and Child Surrounded by Saints (detail), between 1350 and 1365, Follower of Bernardo Daddi (possibly Pietro Nelli). Tempera and gold leaf on panel, 37 ½ x 26 in. Portland Art Museum, 61.51

Coppini and Aldobrandini arms from the Ceramelli Papiani

An illustrious copy of Dante’s Divine Comedy on loan from The Morgan Library & Museum bears the arms of Dante’s own family, the Alighieri (you can see the manuscript here). Francesca Pasut, a specialist on 14th-century Dante manuscripts, wrote in the exhibition catalogue that the Morgan manuscript is one of six copies of the Divine Comedy illuminated by Pacino di Bonaguida in Florence for the Alighieri family. The Divine Comedy’s popularity is astounding considering that it was written and disseminated in a time long before email, let alone the printing press!

Left: Initial L: The Coronation of the Virgin in Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, about 1337, Pacino di Bonaguida. Tempera and gold leaf on parchment, 14 5/8 x 10 7/16 in. Archivio Storico Civico e Biblioteca Trivulziana, Ms. Triv. 1080, fol. 70

Right: The Crucifixion in a Missal, about 1330-40, Pacino di Bonaguida. Tempera, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, 13 9/16 x 9 5/8 in (34.5 x 24.5 cm). Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, Ms. N.A. 1168, fol. 152

A few of the objects in the exhibition—including another copy of Dante’s Divine Comedy and a Missal (containing the prayers said by the priest at Mass)—once had coats of arms, which appear to have been removed in a later period, perhaps due to a change in ownership. Elsewhere in the Missal, there is a remnant of a cardinal’s cap, or galero, above another effaced escutcheon, suggesting that the manuscript was originally made for an ecclesiastical patron. In the Divine Comedy, which is the earliest illuminated and dated copy of Dante’s text (from 1337), the arms have been completely scraped away, leaving no clues for determining the book’s earliest owner. The scribe, however, included his name in a colophon at the end of the manuscript: Francesco di Ser Nardo da Barberino, who was renowned for his elegant penmanship.

Initial L: The Coronation of the Virgin (detail) in Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, about 1337, Pacino di Bonaguida. Tempera and gold leaf on parchment, 14 5/8 x 10 7/16 in. Archivio Storico Civico e Biblioteca Trivulziana, Ms. Triv. 1080, fol. 70

The Peruzzi Altarpiece, painted by Giotto di Bondone, is named after the Florentine banking family who presumably commissioned the polyptych (the only intact polyptych by Giotto outside of Italy). The painting does not bear a coat of arms, so art historians rely on other types of evidence when trying to deduce the original patrons of the piece. In 1931, Wilhelm Suida first connected the polyptych with the Peruzzi family, citing a passage from I commentarii (about 1447) by Lorenzo Ghiberti in which the 15th-century sculptor claimed to have seen four altarpieces in chapels frescoed by Giotto in the Church of Santa Croce in Florence. The Peruzzi were among the families with a private chapel in the church, and what’s more, their chapel boasted a series of frescoes by Giotto depicting scenes from the lives of Saints John the Evangelist (at far left in the polyptych) and John the Baptist (between Christ, center, and Francis). Santa Croce is the major Franciscan establishment in Florence, a fact that explains Saint Francis’s presence in the altarpiece. Taken together, this evidence has led to the general consensus that the altarpiece today housed in the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh was once part of the Peruzzi Chapel in Florence (the panels left Florence as early as 1926).

Peruzzi Altarpiece, about 1309–15, Giotto di Bondone and His Workshop. Tempera and gilded gesso on poplar panel, 41 5/8 x 98 1/2 in. North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, Gift of the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, GL.60.17.7

Now I turn to you, readers, because there is one coat of arms in the exhibition that I have been unable to decipher. On loan from the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco is a desco da parto, a tray or salver used to transport food to a new mother, with the arms of the Salviati family (left) and those of an unidentified family (right). The label gules placed at the top of the arms perhaps designate that they belonged to the eldest son of a family (gules is a designation for the color red and label is the horizontal dovetail band in chief position at the top of the coat of arms). The official heraldic designation is as follows: Paly of six, or and gules, on a bend sable (or azure?), with label gules. Do you recognize the arms? Any leads are greatly appreciated!

Childbirth Tray (desco da parto) with Justice (verso), about 1380–1400, Lorenzo di Niccolò (possibly by the Master of the Lazzaroni Madonna). Tempera and gold leaf on panel, 25 1/8 x 25 3/8 in. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, Roscoe and Margaret Oakes Income Fund, 78.78

Corsini?

Alberti (Firenze)

http://wikipedia.sapere.virgilio.it/wikipedia/wiki/Armoriale_delle_famiglie_italiane_%28Al%29

halfway down

It is certainly a wonderful thing that internet resources have made the identification of Renaissance coats of arms easier, but a note of caution: not everyone with a given surname may be entitled to use the coat of arms of a family with the same surname, and the same coat of arms (especially if it is has relatively simple elements) might be used by entirely unrelated families. Happy researching, Hugh.

I haven’t seen Justice represented with wings. It might not be justice. It might be the Archangel Michel with the balances for weighing souls.

Gavin O’Brien

The nearest I could find is the following: http://www.archiviodistato.firenze.it/ceramellipapiani2/index.php?page=Famiglia&id=6540

The use of the octagon halo is, according to information in the exhibit, characteristic of personified qualities and not actual persons such as saints. If so, St. Michael seems less likely than justice as the subject of this image. Coats of arms are open to interpretation; the one for my family is claimed to represent the naming by a king (allegedly Peter the Cruel of Castile) of the first person with the family name, for saving him in battle. The king is shown as a lion leaning against the apple tree and thence the family name. But a later argument was that the name was Sephardic and the legend a cover for its Jewish origins. I presume the idea of coats of arms was just an exercise in self promotion, a symbol easily recognized when literacy was infrequent. Who was the originator and who the designer and what was meant is the rest of the story.

Heraldry of vanzin plrase, is from my family