Discover how scholars learn to decode the strokes, jots, tittles, and marks of historical penmanship

The 2014 class of the Mellon Summer Institute in Italian Paleography at the Getty Center at sunset

For three weeks in July, I spent my mornings with sixteen other scholars craning over documents, squinting at centuries-old squiggles in the hope that the written forms would become comprehensible letters. At first, it seemed like the parchment or paper held a secret message in an unknown alphabet—certainly not the Italian we expected to find.

Slowly, with many mistakes and false starts, one symbol would begin to make sense. Next, another would fall into place. Amid a torrent of antiquated abbreviations and seemingly meaningless marks, letters, words, and sentences would literally come into focus before our eyes, leaving us shocked that we had not understood the message in the first place.

Many students of the humanities in Europe receive training in how to decipher the handwriting of the past, but here in the States many of us are woefully distant from all things old. The Mellon Summer Institutes at the Getty Research Institute and the Newberry Library Center of Renaissance Studies in Chicago are helping to bridge this gap. Offering training in paleography in Italian, Spanish, English, and French, these programs provide keys to unlock the treasure chest of the past, unleashing meaning from long forgotten documents. This year’s focus was Italian, and we explored a range of documents from Dante’s Divine Comedy to inventories of extravagant art collections.

Learning to Read, Again…

Paleography is the study of old handwriting. (You can learn more about the subject in Eloise Lemay’s informative post from last year’s Institute, What Do Paleographers Do?). Little makes a researcher feel more like an adventurer than successfully deciphering an old and complicated document. Gandalf used paleography to decode the map to the Lonely Mountain; Indiana Jones needed it to read the tablet that would lead him to Holy Grail. Indeed, handwritten materials are history in its rawest, and perhaps purest, form. In them we have the most direct access possible to the minds of people in the past.

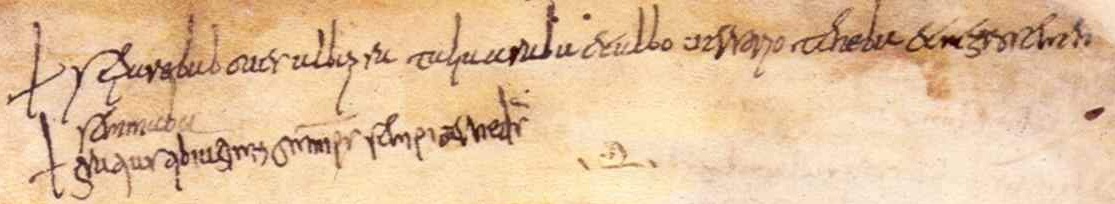

![Indovinello Veronese, about 900 AD, ink on parchment. Biblioteca Capitolare, Verona [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Indovinello_veronese.jpg]](http://blogs.getty.edu/iris/files/2014/09/Indovinello.jpg?x45884)

Indovinello Veronese, about A.D. 900. Ink on parchment. Biblioteca Capitolare, Verona

Using your own paleography skills, you might decipher the following in the first line below:

se pareba boves / alba pratalia araba / alba versorio teneba / negro semen seminaba.

In English this means:

In front of him (he) led oxen / White fields (he) plowed / A white plow (he) held / A black seed (he) sowed.

Indovinello Veronese (detail), about A.D. 900. Ink on parchment. Biblioteca Capitolare, Verona

It’s both humbling and astounding to realize that history is written from the documentary shards of a past now long gone. Paleographic skills are necessary to piece together and make sense of the remnants.

Beautiful writing was cultural capital, too. Even in the 16th century, when print books were flowing rapidly from presses across Europe, writing well proved one’s good breeding and meant that one could always find employment as a scribe. Printing presses stamped out books that described the ins and outs of a cursive script known as cancellaresca, and contemporaries would buy such guidebooks and practice their own handwriting in the margins.

Paleography at the Getty

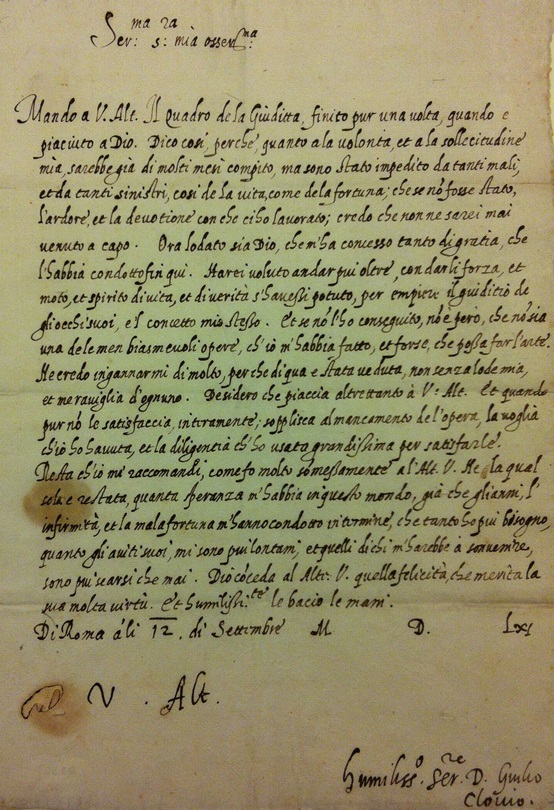

The Getty Research Institute has a diverse array of sources written in Italian, including many concerning art and collecting. In an inventory drawn up in 1733, we find ourselves drooling over the art owned by Carlo Strozzi in his palace and villas in Florence. Other documents allow us to peer over the shoulders of an artist as he makes excuses to his patron. In a letter from 1561, the famous manuscript illuminator Guilio Clovio apologized to the Duchess of Parma for his procrastination in delivering the painting of “Giuditta” (Judith). “Sinister things,” he complained, delayed him from finishing this work, which lacked some of the “spirit of life” he had wished to put into it.

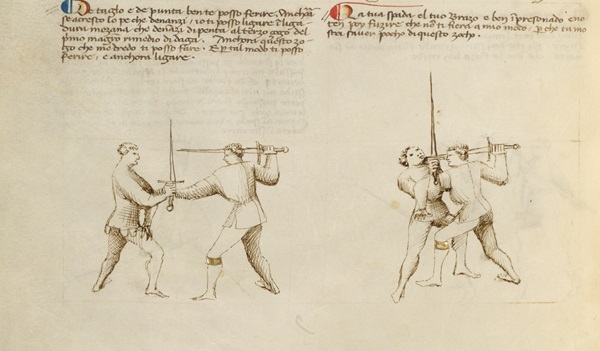

The Mellon Summer Institute in Italian Paleography was a thrilling experience, if at times greatly challenging. Together with scholars of literature, art, library science, and architecture, I took a journey through Italian history by way of handwriting. Many of us had come to the Summer Institute to acquire proficiency in reading the specific documents for our research, from the archaic abbreviations in medieval Arthurian manuscripts to the wild twists of Palermitan scribal hands to the instructions of an accomplished swordsmith. We came away from the workshop with a toolkit to crack open both our own documents and others, emerging with a rich sense of the parallel histories of handwriting and of Italy.

Combat with Swords (detail), from Fiore dei Liberi, Fior di Battaglia, possibly Venice or Padua, ca. 1410. Tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, 11 x 8 1/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XV 13, fol. 20v

Text of this post © Mackenzie Cooley. All rights reserved.

A fascinating article that brings the subject matter to life.

And I spent a few weeks in August pouring over family letters and inventories wondering in many cases what was she saying? As it is the Aunts in the prior generations that did the writing that was saved. It was interesting “history” – not much of which was told to us as children.