Spared two centuries ago from being lost at sea, a Greek vase makes the crosstown trip from the Miracle Mile to Malibu

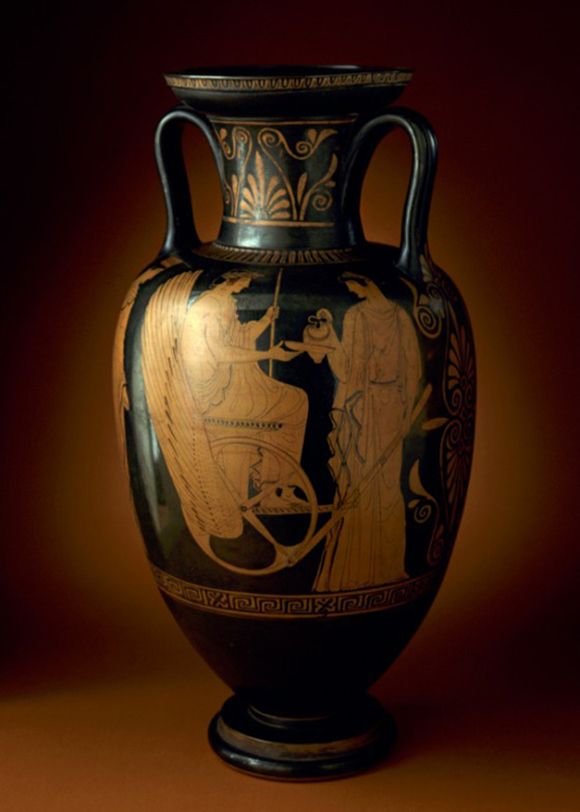

Red-Figure Neck-Amphora with Triptolemos Attended by Demeter and Persephone, about 440–430 B.C., attributed to the Hector Painter. Greek, made in Attica. Terracotta, 19 1/4 in. high. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art, William Randolph Hearst Collection (50.8.23). Photograph © Museum Associates/LACMA

The exhibition Sicily: Art and Invention between Greece and Rome opens at the Cleveland Museum of Art this Sunday. Those of you who were able to see the exhibition at the Getty Villa—or who have enjoyed the accompanying publication—will know that it includes a stellar array of sculpture, metalwork and vase-painting from sites and museums throughout Sicily. The exhibition also features a number of objects from the Getty’s collection, such as the Athenian red-figure footed dinos normally on display in our Gods and Goddesses gallery.

Mixing Vessel with Triptolemos, about 470 B.C., attributed to the Syleus Painter. Greek, made in Athens. Terracotta, 14 1/2 x 14 1/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 89.AE.73

Through the generosity of our colleagues at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), we’ve temporarily replaced it during the run of the Sicily exhibition with another vase that shows a similar scene: the young Triptolemos seated in his winged chariot, ready to share the secrets of agriculture with the world, and the goddesses Persephone and Demeter preparing him for the journey.

Display case at the Getty Villa featuring, at center, Red-Figure Neck-Amphora with Triptolemos Attended by Demeter and Persephone, about 440–430 B.C., attributed to the Hector Painter. Greek, made in Attica. Terracotta, 19 1/4 in. high. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art, William Randolph Hearst Collection (50.8.23)

If Triptolemos was famous in antiquity for his travels, the story of how this particular vase reached Los Angeles is also worth describing. For it first belonged to Sir William Hamilton, one of the most important figures in the history of collecting Greek vases. As British envoy in Naples from 1764, he was witness to an effusion of archaeological discoveries and built up a stunning collection of Greek vases. He published these between 1767 and 1776, and sold the collection to the British Museum. Increasing prices, along with a Neapolitan decree preventing landowners from excavating on their estates, brought a pause to Hamilton’s collecting, but after the ban was lifted in 1789, he resumed with eagerness. He rapidly assembled a second collection, which included the neck-amphora with Triptolemos now at LACMA, and these were published with illustrations by the German artist Wilhelm Tischbein (1751–1828).

With the publication of this collection underway during the 1790s, Hamilton then set about to sell his vases, but the French invasion of Italy in 1798 prompted him to ship his belongings for safety back to England. His vases were packed into 24 cases, and eight of these were loaded onto the HMS Colossus. But as the boat took shelter near the Scilly Isles (off the southwest coast of England) toward the end of its journey, it was struck by gale-force winds and sank. Desperate attempts were made to salvage the cases, but without success. One contemporary report of the wreck noted that the locals, making keen efforts to rescue what they could, saw fragments of vases—but to no avail. The news was grim for Hamilton, and he despaired. For the eight cases that had been loaded on to the Colossus were, he presumed, those that contained the finest of his vases. Still in Naples, he wrote:

“All the cream of my collection were in those eight cases on board the Colossus and I can’t bear to look at some of the remaining cases here in which I know there are only black vases without figures.”

—William Hamilton to his nephew Charles Greville, January 25, 1800. Quoted in Valerie Smallwood & Woodford (see references at end of post)

But after returning to England with the rest of his collection, Hamilton’s despondency turned to delight. For there had been a mixup at the docks. The eight crates that had been put aboard the Colossus had in fact contained undecorated and plainer vessels (they were finally recovered almost two hundred years later, and have been intensively sorted and studied by curators and conservators at the British Museum). Through sheer chance and good fortune, Hamilton’s finest wares—including the LACMA Triptolemos vase—had remained intact and were safely with him in London.

In need of money, Hamilton resumed plans to sell his vases, and they were purchased in bulk by Thomas Hope, another key tastemaker and collector based in England. They remained in the Hope family until 1917, whereupon they were sold at auction. Nearly 30 years later, a number of these vases—again, including the LACMA Triptolemos—came up for sale and were purchased by William Randolph Hearst. As with Hamilton and Hope, Greek pottery was one of Hearst’s many passions, and today vases can still be seen in situ in the magnificent library at Hearst Castle at San Simeon. The collapse of Hearst’s finances in the 1930s brought about the dispersal of much of his wide-ranging collection, but he (like Hamilton) resumed his purchases after a forced hiatus. Toward the end of his life, he decided to donate certain objects in his collection to the Los Angeles County Museum of History, Science and Art (part of which would later become LACMA), and soon became the museum’s most important benefactor, donating some 900 objects. The Triptolemos vase was one of 42 figure-decorated Athenian vessels that he gave to LACMA in 1950, a year before his death.

We are delighted that Triptolemos has been given the opportunity to continue his westward travels and temporarily grace our galleries, where he will remain on view for the rest of this year.

Suggestions for further reading

- Ian Jenkins and Kim Sloan (eds.), Vases and Volcanoes. Sir William Hamilton and His Collection (1996)

- Mary Levkoff, Hearst the Collector (2008)

- Roland Morris, HMS Colossus: The Story of the Salvage of the Hamilton Treasures (1979)

- Nancy H. Ramage, “Sir William Hamilton as Collector, Exporter, and Dealer: The Acquisition and Dispersal of His Collections,” American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 94, No. 3 (Jul., 1990), pp. 469-480

- Valerie Smallwood and Susan Woodford, CVA, British Museum 10 (Fragments from Sir William Hamilton’s second collection of vases recovered from the wreck of HMS Colossus) (2003)

- David Watkin and Philip Hewat-Jaboor (eds.), Thomas Hope: Regency Designer (2008)

Will there be a chance to see the two Triptolemos vases side-by-side once the Getty dinos returns? It would be terrific to explore how two different vase painters depicted the same scene.

Alas not—the LACMA vase will return once our vase is back on display. But if you want to compare different treatments of the same scene, we do have two depictions of Herakles’ battle with the Hydra on view: one on a Caeretan hydria, and this earlier Corinthian oil jar. If it’s Triptolemos that you’re specifically interested in, I’d recommend searching within the Beazley Archive’s database.