Daniel Kelm is a book artist, sculptor, book binder, and teacher. His intricate, detailed works invite unconventional ways of reading—which can resemble unearthing a mystifying treasure or solving a 3-D puzzle—and they condense wondrous topics that have laid between book covers for centuries—like alchemy, mathematics, science, metaphysics, maps, and illustrations—within visually astonishing bindings.

He invented the widely-used “wire-edge binding” and is the founder and proprietor of Wide Awake Garage studio in Easthampton, Massachusetts, where he designs and produces artist’s books and innovative sculptural bindings. His work has been shown nationally for over thirty years, and he has taught and lectured at universities and libraries in the U.S. and Europe.

Kelm comes to the Getty Center on October 26 to give a lecture, along with book artist Timothy C. Ely (see my interview with him in this blog post), on the role of alchemy in their work. In advance of his visit, I asked him a few questions about his extraordinary work.

Lyra Kilston: Your work expands the form of what most people think of as a book: your works don’t need words, or images, or to open in an arc. In your view, what is the outer limit of having something remain a ‘book’?

Daniel Kelm: Books are a wonderful vehicle for telling stories. Most often the book artist constructs the book around their or an author’s story. Many of my books contain no recognizable words, but are made of shapes that allow wide-ranging flexibility and movement. They are actually quite toylike, and if successful engage the “reader” in the same physical and interactive way as do toys. During that play, these wordless books can inspire someone to discover their own voice and story. I love watching someone interact with one of my sculptural books, then suddenly stop to tell one of their own stories.

Do you have a favorite rare or ancient book? Have you been able to see it in person?

My library is bulging with rare books that tell the story of someone’s exploration of the physical world. One of the books that I visit in a local college rare book room, though, is remarkable for its wealth of evocative language—the 1689 English edition of Johann Rudolph Glauber’s Complete Works. Glauber (1604–1670) considered himself a chymist (an archaic term similar to chemist), but his language is alchemical, mythological, and poetic.

What are some of your favorite materials to work with?

I love working with vegetable-tanned goat skin, a material commonly used in traditional fine bookbinding. For non-traditional work I tend towards metal, glass, and plastic. I’ve not found any material to be too rare or impossible to find and work with; there is always a way to invite it to play. In all cases, whatever the material used, it is important to discover its voice and to let that voice support the story being told.

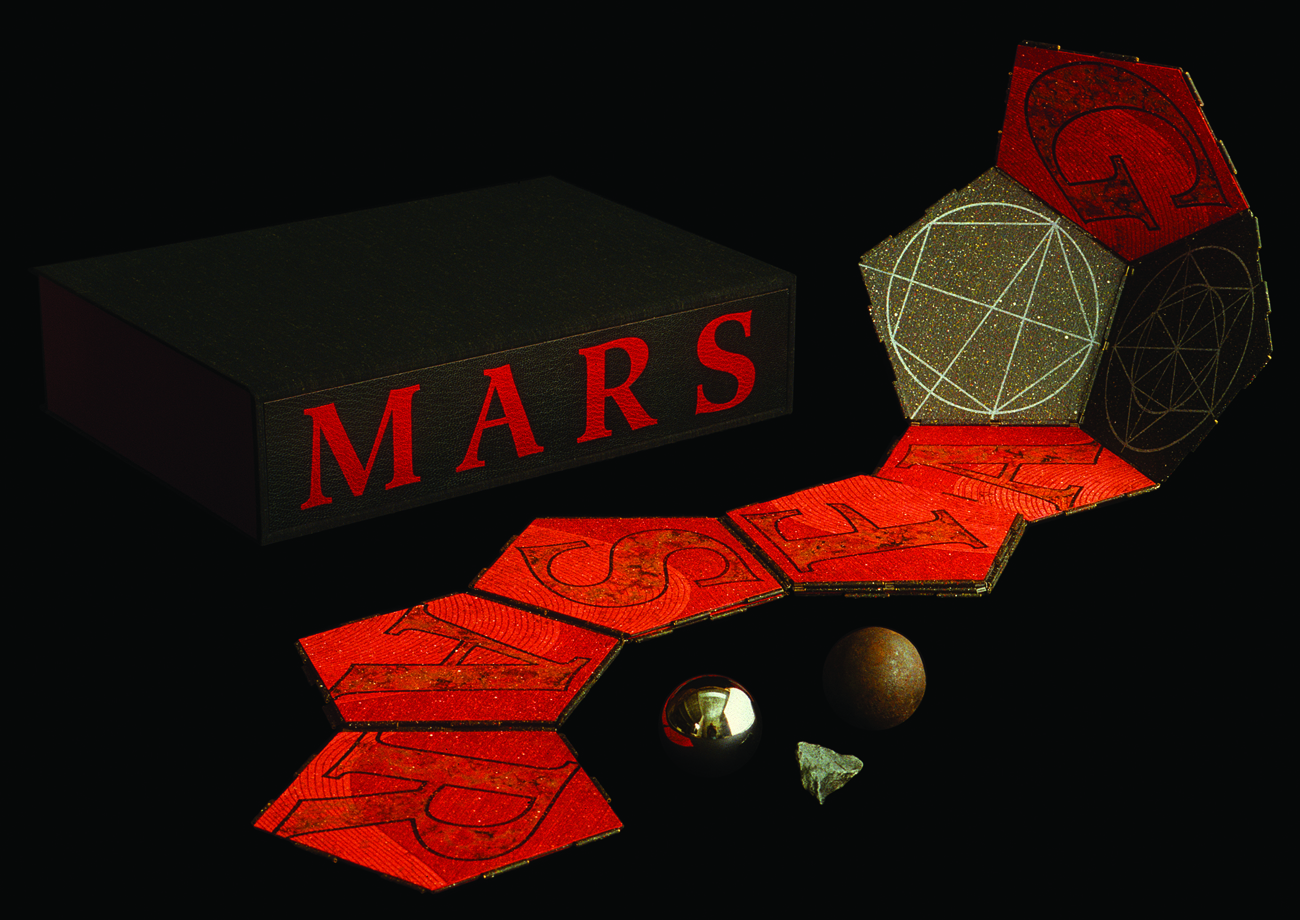

Mars, 1991–2005, Daniel Kelm. 11.5 x 8 x 3 in. (closed). Contents: box, accordion book partially pinned together, and three objects representing various aspects of Mars. Materials: paper board, paper, acrylic paint, thread, stainless steel wire, dry-mount adhesive, iron nickel meteorite, chrome steel ball bearing, Civil War iron canister ball, felt, fiber board, cloth. Techniques: wire edge binding, painting, photo copy transfer, airbrush, paste paper, silk screen printing, letterpress printing. Voice of Mars text by Taz Sibley. Letterpress printing by Art Larson.

What themes have you been working with recently?

After 20 years immersed in chemistry, I began a thirty-year study of alchemical processes that has inspired many of my artist’s books and sculpture. Experimentation with plant alchemy (spagyric alchemy) led me to an appreciation of pharmacy. In my latest work I’m exploring chemical and pharmaceutical processes through installations combining laboratory apparatus with antiquarian books describing the process.

I look at the installations as functional sculpture. The animating voice of each piece is that of the chemist, pharmacist, researcher, or lab worker who developed and explained the particular approach, so their name is usually intimately associated with it.

What is your research process like?

I often start with a description of a process or an image of the associated apparatus and then find out everything that I can about it, including details about the life of the person who developed it. My work always tries to integrate the personal connection (through the life of the individual associated with the science involved), the historical (by choosing a process that has been proven through its historical record to be significant to our lives), the aesthetic (as seen in its sculptural quality), and the technical (the details of the process and materials themselves).

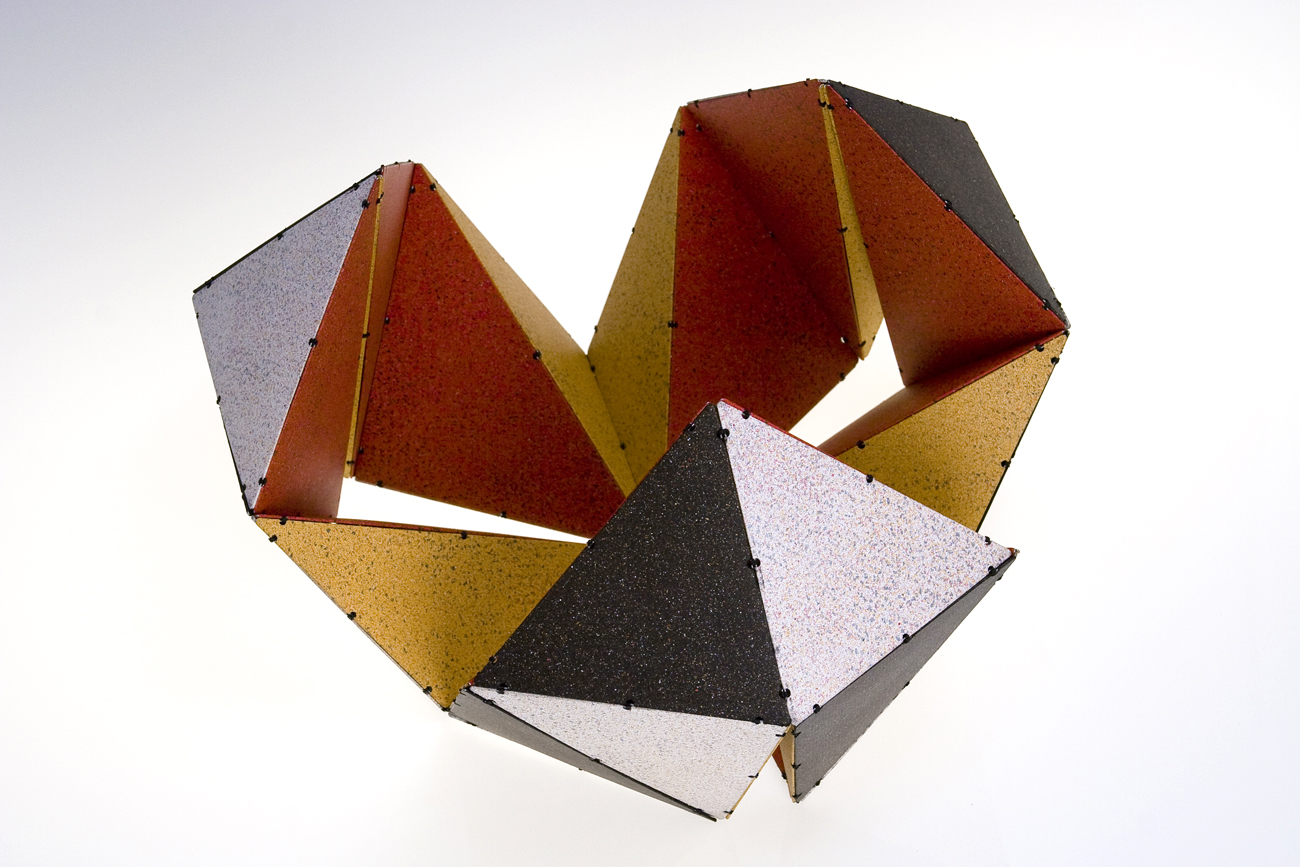

Relgio Mathmatica, 1990–2007, Daniel Kelm. 9 x 9.5 x 9.5 in. Materials: paper and paper board, stainless steel wire, thread, English yew wood, paint, leather. Techniques: wire edge binding, spattering, paste paper. Photographer: Jeff Derose, One Match Films. Binding assistance by Kylin Lee. This video of Kelm manipulating the binding shows how the “Lotus Flower” configuration closes—the red cube moves to the inside, and the black and white surfaces to the outside.

Comments on this post are now closed.