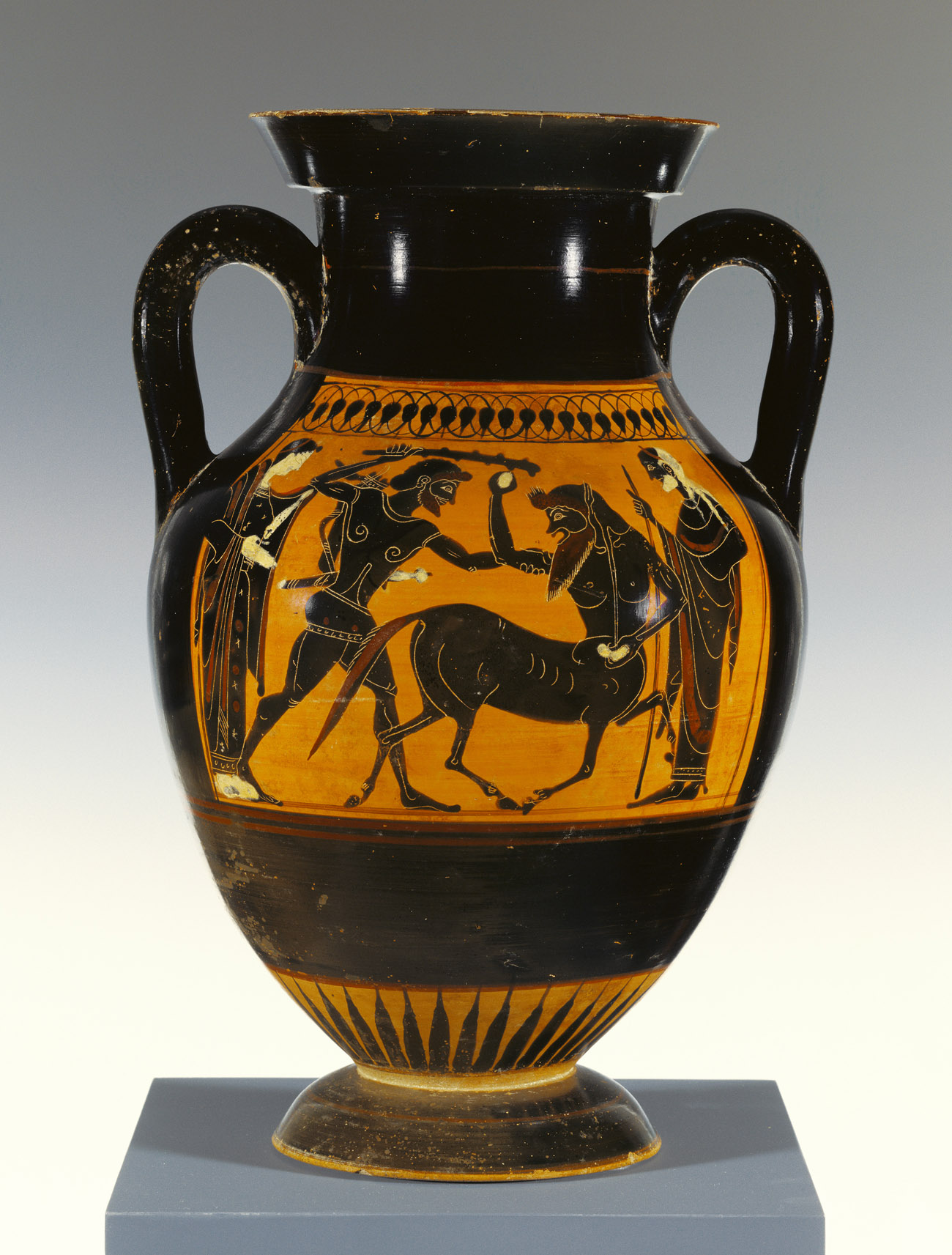

Storage Jar with Herakles Attacking a Centaur; Attributed to the Medea Group (Greek (Attic), active 530 – 510 B.C.); Athens, Greece; 530 – 520 B.C.; Terracotta; 34 × 22.1 cm (13 3/8 × 8 11/16 in.); 88.AE.24

Attic pottery, the iconic red- and black-figure vessels produced in ancient Greece from the 6th to the 4th centuries B.C., like this storage jar at the J. Paul Getty Museum, and this mixing vessel in the collection of the Met, required immense precision to produce, and the means by which craftsman created it is still not completely understood.

Now, thanks to a National Science Foundation SCIART grant, a collaborative group of California scientists from the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI), The Aerospace Corporation, and the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory (SLAC) at Stanford is investigating the ancient technology used to create these works of art, and will use their research into the makeup of this beautiful pottery to further current conservation practice and future space travel.

It’s hard to imagine a more dissimilar-sounding pairing, but the technology is actually quite transferable.

Karen Trentelman, a conservation scientist at the GCI, tells me the grant team, working with conservators and curators from the J. Paul Getty Museum, already is analyzing fragments of ancient pottery. Fragments attributed to specific artists will enable the material “signature” of known artists to be established, which should help with the attribution of unsigned works. In the process, the information the scientists discover will provide a deeper understanding of ancient pottery techniques, inform future conservation methods, and create a deeper knowledge of iron spinel chemistry—used in the advanced ceramics found in aerospace applications.

J. Paul Getty Museum associate conservator Jeffrey Maish examining an Attic black-figure kylix under a binocular stereo-microscope. Getty Conservation Institute

“Ceramic components are used all through space technology and space vehicles. We need to continue to learn about interactions of components within these materials to help us better understand any real-world issues that may arise in actual space components,” explained Mark Zurbuchen, a materials scientist with the Aerospace Corporation. Interestingly, Zurbuchen also is an amateur potter.

“I have a first-hand perspective of how clay works,” Zurbuchen told me. “Molding clay is very much about precision and craft. As a scientist and a potter, I find this project fascinating from both viewpoints.”

“By partnering with SLAC and the Aerospace Corporation, we, too, can look at the artwork in a new way,” Trentelman told me.

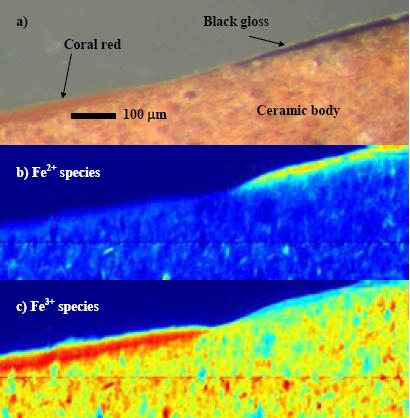

For example, she explained that, with such highly specialized equipment, the GCI’s partners can help them to investigate at a very minute level such things the iron oxidation levels in a ceramic work, which causes either the striking bright red color seen on Greek vases, or, in its reduced form, the black color, both of which are difficult to measure.

The funding from the NSF grant will in large part be used to support a postdoctoral student who will be able to work in all three labs in three very different environments. The primary scientific techniques the team is using are X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES), a spectroscopic tool used to determine iron oxidation states in the Attic pottery; X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS), which provides information on the molecular structure of the iron minerals; and high-resolution digital microscopy, to study the surface of the work.

XANES maps a) optical image showing black gloss (right) and coral red (left), b) distribution of Fe2+ species (measuring iron present in an oxidation state), and c) distribution of Fe3+ species (measuring specific minerals present). Getty Conservation Institute

Aside from these highly technical aspects of the work, all of the scientists also are keenly interested in the sociological aspects. In other words, what impact did these ancient Greek potters have on their greater community?

For GCI scientist Marc Walton, who helped Trentelman develop the grant proposal, the project is about understanding the society in which these pots were made.

“Using scientific methods, we want to look at the sociological context of ancient Greek workshops and potters and re-establish what we know about them,” said Walton from his GCI research lab at the Getty Villa.

At SLAC, which houses a high-powered X-ray source driven by a particle accelerator called a synchrotron, staff scientist Apurva Mehta is working with the team to reveal nanoscale details across large regions of ancient vessels. This work, Mehta said, will push the development of high-powered tools to probe many other materials, from biomaterials to electrodes of lithium-ion batteries. His work also will help uncover answers to some important questions.

“There were several workshops making this pottery at the same time,” said Mehta. “It’s a fairly challenging technology. How it was it invented? Did one workshop invent it and other workshops copy, modify, and perfect it? Were they collaborating or competing with each other? I want to understand how technology really works in a society. How does a technology grow, how does it transfer from place to place, how does it change, what keeps it alive, why do some technologies eventually die away? Maybe this will help us understand how technologies are growing and changing today.”

Using the information gleaned from the scientific studies of ancient vessels as a guide, the group even plans to reproduce the technology used by early artisans by firing small replicas.

The scientists ultimately hope to uncover whether works attributed to different artists used the same methods, or if techniques for creating the work differed across workshops that were producing pots at the same time. They also hope to document how the process evolved over time. The results are expected to benefit a diverse range of fields in both art and science, including materials science, chemistry, archaeology, art history, and art conservation.

“Scientific analysis gives us new insight into how and when the work was produced. In turn, our analysis can support hypotheses developed by art historians about ancient workshop practices, and also inform museum conservation efforts,” said Trentelman. “Using nothing but clay dug from the ground, ancient craftsmen were able to create magnificent vessels with amazing detail. Something doesn’t need to be complex to be sophisticated. If we can understand the technology with which these works of art were made, we can use the knowledge for a surprisingly wide variety of applications.”

Often, it seems, we have to look to the past to help inform the future. But ancient pots and space travel? Fascinating.

I remember that a German scientist published a paper on how the Greek potters achieved their red and black designs some time in the late 50s or early 60s. If I remember correctly his name was Mueller, but I am not certain.