Cover and illustration from the copy of Bulwer-Lytton’s The Last Days of Pompeii in the special collections of the Getty Research Institute (London, William Nicholson, ca. 1883)

Mount Vesuvius erupted on August 24, A.D. 79, burying Pompeii and neighboring towns under tons of ash and volcanic debris. Rediscovered by accident some 1,650 years later, the Vesuvian ruins captured the imagination of artists and writers, who vied to depict the catastrophe as vividly as possible.

In the 19th century, no figure mined Pompeii for more O!’s and Alas!’s than novelist Edward Bulwer-Lytton (of bad writing contest fame), whose 1834 potboiler The Last Days of Pompeii was hands-down the most popular novel of the age. The book had such a dramatic impact on how we think about Pompeii that we’ve borrowed its title for the upcoming exhibition The Last Days of Pompeii: Decadence, Apocalypse, Resurrection, opening September 12, which examines how our contemporary concerns shape the ways we view the past.

Being a (mostly) proper Victorian Englishman, Bulwer-Lytton’s concerns in The Last Days of Pompeii were morality, sin, and religion. He paints a picture of Pompeii on the eve of its doom as a cesspool of vice, greed, gluttony, indolence, sexual debauchery, idolatry, and, worst of all, bad taste. His Romans come in three breeds: dissipated patricians, venal plebeians, and uncouth rabble. His heroes are all Greeks, plus a few early Christians who provide a patch of light.

In brief, the novel follows two interlocking love triangles. At the center is the romance of two well-born Greeks, Glaucus and Ione, who must escape the grips of evil Egyptian priest Arbaces, who lusts after Ione. A delicious foe, Arbaces combines infinite wealth with magical powers and political acumen. The most complex, and therefore the most engaging, character is the Thessalian slave Nydia, a blind tweenage flower-seller. Alternately peevish and noble, childish and wise, she pines hopelessly for Glaucus. Nydia was a favorite subject of artists, and the exhibition includes no fewer than three versions of Randolph Rogers’s statue of her. His Nydia was one of the most popular sculptures of the 19th century, with over 160 carved. This tender canvas by Lawrence Alma-Tadema from the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art, which co-organized the show, pictures a tender moment between Nydia and Glaucus before the fiery end.

Glaucus and Nydia, 1867, Lawrence Alma-Tadema. Oil on wood panel, 15 3/8 x 25 5/16 in. (39 x 64.3 cm). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Noah L. Butkin, 1977.128

Vesuvius casts its long shadow over every page of The Last Days. The Romans’ frettings about money, status, and dinner parties seem all the more decadent and perverse since their doom is nigh. We, civilized modern peoples, would never worry about such things! And Arbaces is so unkillable that only a lightning strike, which cinematically topples a massive column, can end him. I admit it: at times, I longed for the eruption. The blinding ash, hurtling rock, and choking vapors are a long-awaited Last Judgment that immolates the sinners and lifts the virtuous to paradise (read: Athens). Bulwer-Lytton makes you stop worrying and love the volcano.

As he reveals in his preface, Bulwer-Lytton was moved to pen his novel by a visit to Pompeii’s eerily well-preserved ruins, which cried out to be made alive once again:

On visiting those disinterred remains of an ancient City, which, more perhaps than either the delicious breeze or the cloud-less sun, the violet valleys and orange-groves of the South, attract the traveller to Naples; on viewing, still fresh and vivid, the houses, the streets, the temples, the theatres of a place existing in the haughtiest age of the Roman empire it was not unnatural, perhaps, that a writer who had before laboured, however unworthily, in the art to revive and create, should feel a keen desire to people once more those deserted streets, to repair those graceful ruins, to reanimate the bones which were yet spared to his survey; to traverse the gulf of eighteen centuries, and to wake to a second existence the City of the Dead! Pompeii!

It’s impossible to imagine Pompeii without thinking about the cataclysmic eruption of Vesuvius, which means it’s also impossible to see the city and its inhabitants as they really were. Pompeii is a canvas for the imagination, and this distortion of memory is one of the themes explored by the exhibition through books, photographs, paintings, sculptures, prints, and even a reliquary-style cabinet.

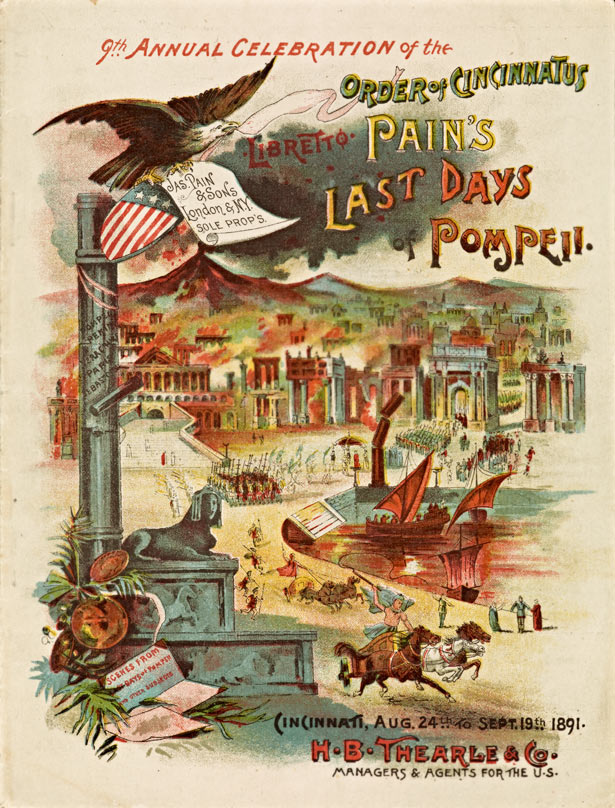

Of course, The Last Days also includes a variety of Bulwer-Lyttoniana, including a copy of the novel from the Research Library at the Getty Research Institute (which you can download or read online here), and numerous objects inspired by its story. My favorite is memorabilia from a late 19th-century traveling “pyrodrama” adapted from The Last Days. The cover of the program from its 1891 stop in Cincinnati, complete with U.S. flag and protective eagle, suggests a particularly American confidence: It could never happen here.

Pain’s Last Days of Pompeii, Libretto cover, 1891, The Thompson Company, Cincinnati. The Getty Research Institute, 2850-629

This is super! Thank you.

Thanks Victoria! I’m really looking forward to the exhibition.

What are the dates of the exhibition?

Hi, The Last Days of Pompeii: Decadence, Apocalypse, Resurrection opens September 12, 2012, at the J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Villa and runs through January 7, 2013.

The exhibition will then travel to the Cleveland Museum of Art (February 24, 2013–May 19, 2013) and to the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec (June 13–November 8, 2013).

I have been researching Pompeii lore through the ages for a novel I am publishing with Harper in 2013, set in contemporary Pompeii. I hope you keep posting the wonderful examples of Pompeii cultural and literary artifacts — and greatly anticipate getting to LA for the show.