For more than a year I have been working on preparing the archive of Barbara T. Smith to be opened to researchers. Smith was a highly influential figure in the development of performance and feminist art in Southern California. Her artistic practice has unfolded over more than 50 years in the varied forms of painting, drawing, installation, performance, video, and artists’ books. The concepts her work explores strike at the core of human nature, such as sexuality, physical and spiritual sustenance, ecology, and death.

The Getty Research Institute (GRI) acquired her papers in 2014. The archive contains 160 diaries, more than 50 sketchbooks with hundreds of drawings, about 850 vintage prints, thousands of negatives and contact sheets, about 90 films, and nearly 1,100 audio and video tapes, in addition to all the notes, plans, and archival records related to her projects from her student days to today.

Now that her archive is ready to be accessed by researchers, I asked Barbara a few questions about her thoughts on the process of the records of her personal life and work becoming a public archive.

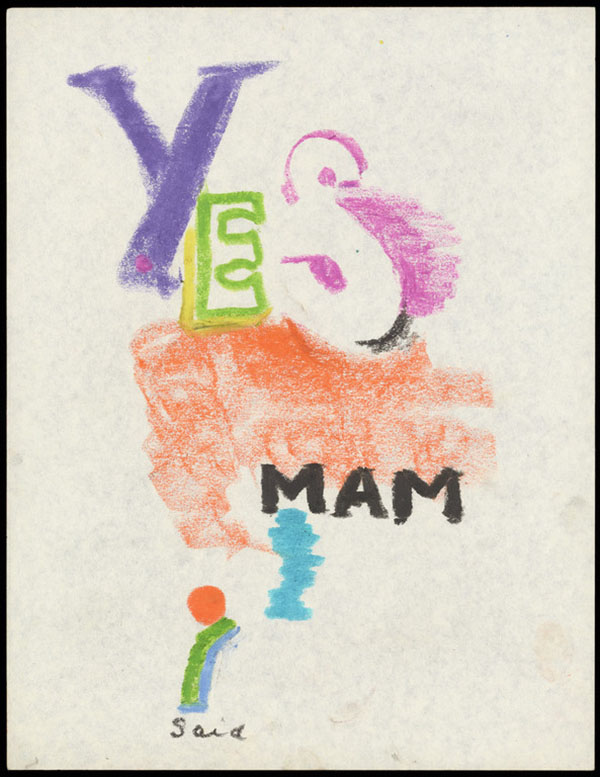

Untitled (Yes Mam I Said), 1965, Barbara T. Smith. The Getty Research Institute, Barbara T. Smith papers, 1927–2012

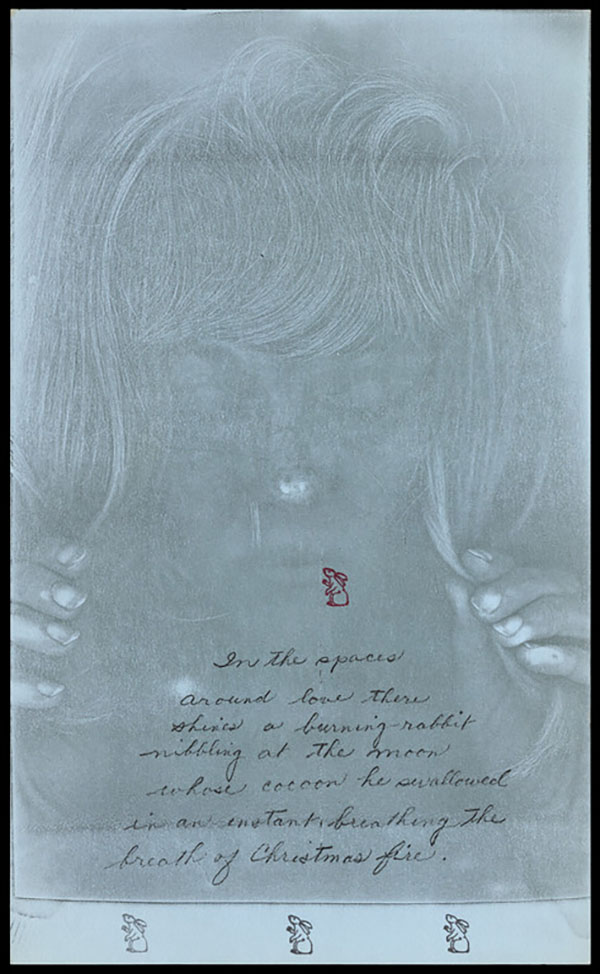

In the Spaces around Love, 1966, Barbara T. Smith. The Getty Research Institute, Barbara T. Smith papers, 1927–2012

Pietro Rigolo: Has creating an archive been something you consciously worked towards?

Barbara T. Smith: I never thought of having a formal archive. I am just someone who saves things. I began to gather the material formally when John Tain [GRI assistant curator] indicated that he was interested in my archive! This was around Pacific Standard Time [a Getty initiative begun in 2011]. At the time I did not even know really what an archive was and given the nature of my work, it proved to be very challenging to figure what items were archival and what was part of my actual art. Performance art has basically no objects and so ephemera from the actual performances and vintage images constitute the extant “art.” So it took about 4 years for us to methodically go through each performance pile and sort it out, “archive” versus “art.” This has made me way more organized, for which I am grateful.

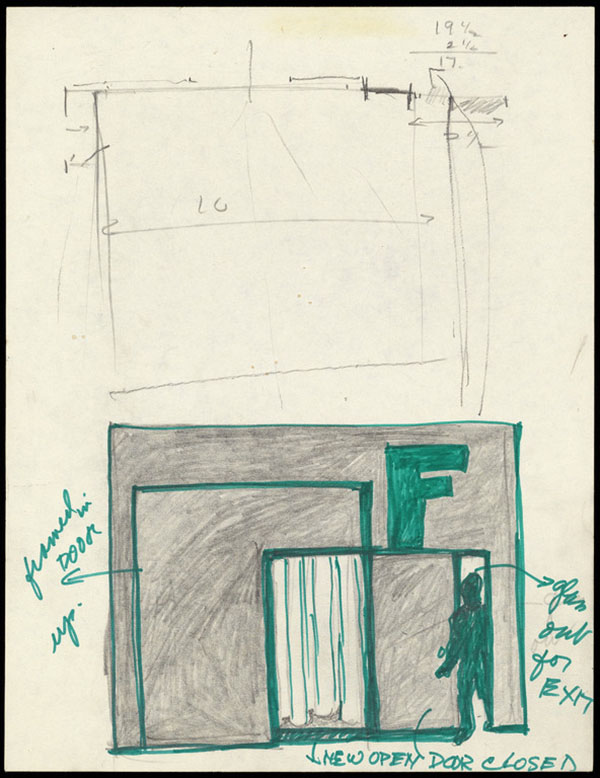

Untitled (drawing for the installation of Field Piece in F Space, Santa Ana), 1971, Barbara T. Smith. The Getty Research Institute, Barbara T. Smith papers, 1927–2012

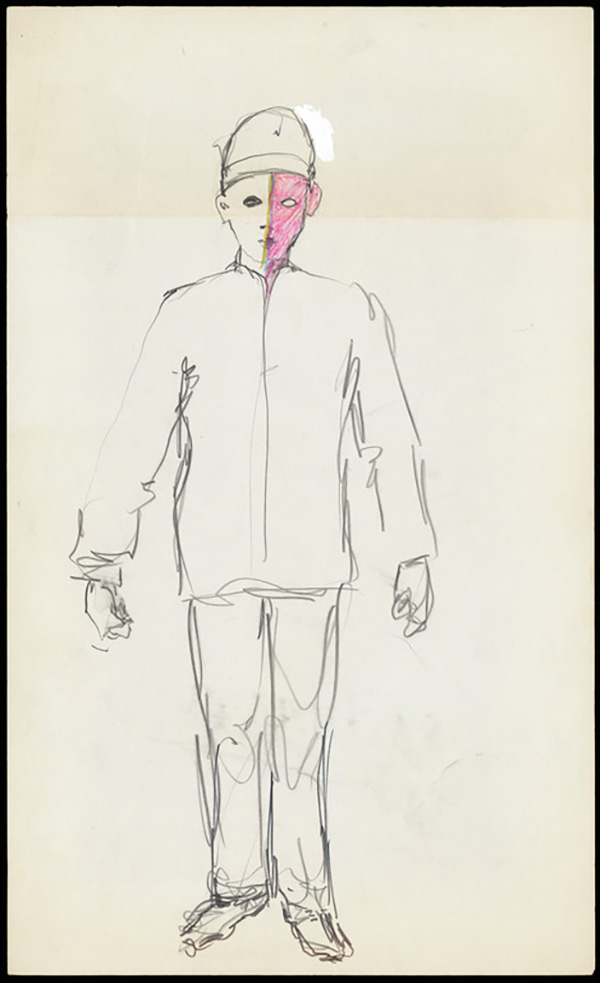

Untitled (drawing of the costume for the performance The Way to Be), 1972, Barbara T. Smith. The Getty Research Institute, Barbara T. Smith papers, 1927–2012

There is a large amount of private information in the archive, such as your diaries, some personal correspondence, and audio recordings of your therapy sessions. How do you draw the line between documents, art works, and personal matter? In other words, what is art and what is life for you? Is there a difference?

Oh gosh! I really didn’t realize that you had some of my therapy recordings. It is all very painful and difficult. The diaries—I call them journals—are included because they connect so directly with the performances, which themselves derive from my life, and also contain, often, drawings and diagrams, etc., that Glenn [Phillips, GRI curator] really wanted. The correspondence is included, much of which is ordinary and mundane, but also sometimes shows the connections I had between other artists, etc. It also gives a glimpse of the end of snail mail and that era. But as I say, it is excruciatingly painful to realize as a result I have very little privacy. It has been surrendered by the nature of my work itself and the acquisition of this archive.

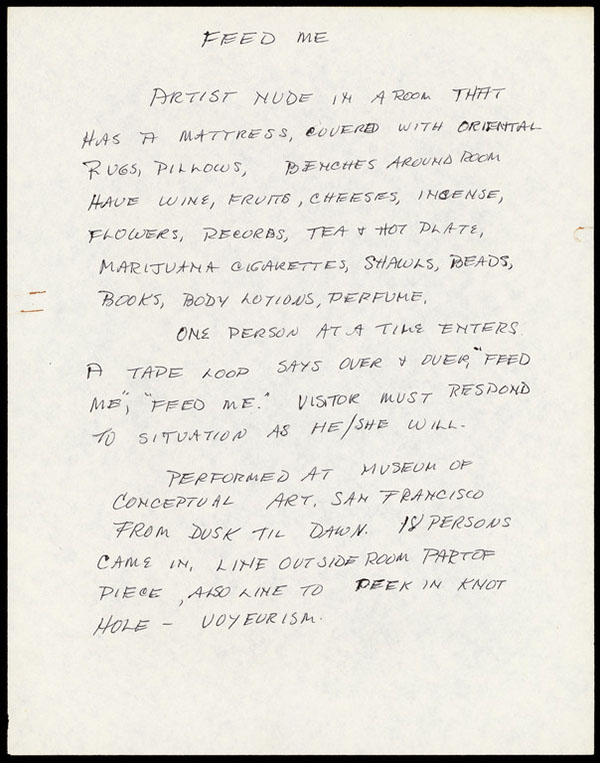

Unpublished note on the performance Feed Me, Museum of Conceptual Art, San Francisco, April 20–21, 1973, Barbara T. Smith. The Getty Research Institute, Barbara T. Smith papers, 1927–2012

The relevance of your papers lies not only in your significance as an artist, but also in its documentation of your deep involvement in the Southern California art scene, for example your participation in F Space with Chris Burden and Nancy Buchanan and your activities with the Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art, the Woman’s Building, and the 18th Street Arts Complex. Would you agree that your papers offer also a specific image of a time, and of a city?

As I said above, this is absolutely true. I was also involved at the Pasadena Art Museum in those days when it was the best avant-garde museum in the country. I worked there as a volunteer for about four, five years (1960–1965). When I was married we [Barbara and her husband] also collected the art of that time. In all this time, Los Angeles has defined itself uniquely as versus any other mega city in the world.

Photo documentation of the performance Pure Food, Costa Mesa, May 1973, Barbara T. Smith. Photograph by Tom Horowitz. The Getty Research Institute, Barbara T. Smith papers, 1927–2012

How does it feel to see your archive down here in the vaults, re-housed and ready to be accessed by scholars and students?

On the one hand I believe it is important for this work to be understood and known because it was indeed very innovative. We all knew we were changing the face of art making. The fact that it is so ephemeral makes it all the more important. However it has been a wrenching experience much like being flayed, if this isn’t too dramatic. By now I think I am over it. The material is gone and it is not me, and I am here a somewhat different person.

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.