In this episode of Art + Ideas, curator Scott Allan discusses two artist biographies: one of Édouard Manet by author and art critic Émile Zola and the other of Vincent van Gogh written by his sister in law Jo van Gogh-Bonger. Both artists proved controversial or difficult during their lifetimes, and these accounts, written by people who knew them well, provide insight into their lives and their art. These texts have recently been published as short books as part of the Getty Publications Lives of the Artists series. Scott Allan is curator of paintings at the J. Paul Getty Museum.

More to Explore

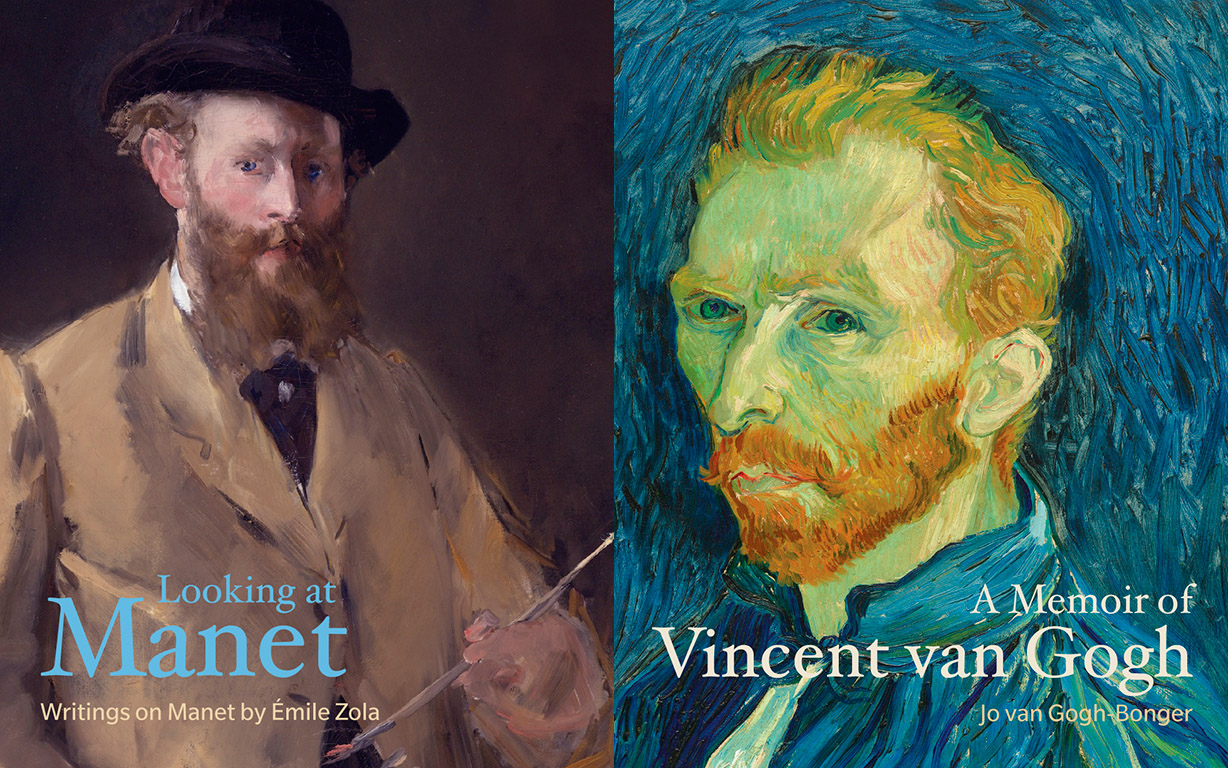

Looking at Manet publication

A Memoir of Vincent van Gogh publication

Transcript

JAMES CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, President of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art & Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

SCOTT ALLAN: Manet, for Zola, represents the most individual, the most original of his time. And so he sees Manet as adding a new note to this unfolding epic of human creation.

CUNO: In this episode I speak with Getty Museum paintings curator Scott Allan about the lives of artists Édouard Manet and Vincent van Gogh.

Édouard Manet was the leading French painter of his day. His father was a high official in the French Ministry of Culture and his mother, the daughter of a French diplomat. There was nothing in his background that would have prepared Manet for the scandal that erupted in 1863, when his painting, Le déjeuner sur l’herbe, or Luncheon on the Grass, was refused by the official Salon and put on view in the alternative exhibition, Le Salon Des Refusés, or the Salon of the Refused works. The painting, of a frankly naked, not nude, young woman in a landscape seated between two fully dressed young men with a second woman in the background dressed only in a chemise, dipping her hand in a stream, attracted howles of outrage from critics.

One critic wrote, “M. Manet plans to achieve celebrity by outraging the bourgeois…His taste is corrupted by infatuation with the bizarre.” Another wrote, “A common breda (a low prostitute from the Bréda quarter]. Stark naked at that, lounges brazenly between warders properly draped and cravatted…these two seem like students on holiday misbehaving to prove themselves men; I seek in vain for the meaning of this uncouth riddle.”

Only Manet’s friend, Zacharie Astruc supported him, and then only with a brief notice in a newsletter issued on the final day of the exhibition, praising the depiction of the landscape in the painting as having “such a youthful and living character that [the Renaissance painter] Giorgione seems to have inspired it.”

It wasn’t until three years later, that the young, aspiring writer, Émile Zola, came to Manet’s defense with an extended article published in 1866 and then republished a year later as a pamphlet accompanying Manet’s large, privately organized one-man exhibition. (Manet was so touched by Zola’s offer to make his pamphlet available at the exhibition that he suggested to Zola that he include an etched portrait of Manet by the artist Félix Bracquemond, opposite the title page, which he did.)

I begin this podcast episode by discussing Zola’s defense of Manet with Getty Museum curator Scott Allan, who is currently organizing an exhibition on the late work of Manet. Scott and I then discuss the life of Vincent Van Gogh, as written by Vincent’s sister-in-law, Jo van Gogh-Bonger, and published in 1914, twenty-four years after the death of the artist.

As is well known, Vincent and his art-dealer brother, Theo, were very close. When they were apart, Vincent wrote hundreds of letters to Theo. The first was written in 1872, when Vincent was 19 and Theo but 15. The last letter, the 901st letter collected in the Van Gogh Musuem’s letter project, was written on July 23, 1890, six days before Vincent took his own life and six months before Theo died of dementia paralytica caused, it was said at the time, by “heredity, chronic disease, overwork, and sadness.”

At Theo’s death, his widow, Jo, inherited 364 paintings and many drawings and letters by Vincent. She took it as her personal mission to memorialize the two brothers by selling and organizing exhibitions of Vincent’s paintings and by publishing his letters. With the appearance of the first volume of the drawings in 1914, she also published an intimate memoir of Vincent’s life. It’s that memoir, together with Vincent’s letters to Theo that have shaped our understanding of the artst’s life.

Both Lives, Manet’s and Van Gogh’s, are featured in the new Getty Publications series Lives of the Artists.

CUNO: Over the past few weeks, I’ve been talking with Getty Museum curators about a series of critical accounts of the lives of artists published by the Getty Publications. These biographies were written, generally, in the lifetime of the artists, and have included Bellini, Raphael and Michelangelo in the sixteenth century, Rembrandt in the seventeenth, and Rodin at the turn of the twentieth century. Today I’m speaking with Getty Museum paintings curator Scott Allan about the lives of Édouard Manet and Vincent van Gogh, written respectively by the novelist Émile Zola and Jo van Gogh-Bonger, van Gogh’s sister-in-law and devoted champion.

Scott, thanks for joining me on this podcast. And let’s start with Manet and the account of his life written by the novelist and contemporary of Manet, Émile Zola. By 1861, Zola was living in Paris. He comes from the South of France, where he was close friends, childhood friends, with Paul Cézanne. And in Paris, he saw Manet’s paintings for the first time. Over the next five years, he witnessed the volatile public reaction against Manet’s paintings, and particularly the famous ones, the Déjeuner sur l’herbe and Olympia, two paintings that depict nudity and sexuality in manners unprecedented at the time.

In 1866, Zola wrote a defense of Manet, writing in part, “Since no one is saying it, I will say it myself. I will shout it from the rooftops. I am so sure that Monsieur Manet will be accounted one of the masters of tomorrow that I think it would be a sound investment, if I were a wealthy man, to buy all of his canvases today. Monsieur Manet’s place is marked for him in the Louvre, like Courbet’s, like that of any artist of strong and uncompromising temperament.” Zola was twenty-six years old at the time and Manet was thirty-three. So Scott, tell us about Manet’s standing as an artist at the time in the mid-1860s, when Zola comes to know him.

ALLAN: Well, by 1865, ’66, Manet had really become very quickly the most controversial painter in Paris, for sure. He had made his debut at the Paris salon, the big official exhibition, state-sponsored exhibition, in 1861. And that year, he actually did quite well and won an honorable mention, on account of a somewhat sober portrait of his parents, and quite a lively picture of a Spanish guitar player, which prompted a rousing ay caramba by the famous French critic Théophile Gautier.

And so Manet had come to some public attention and, you know, shown some promise. But that was quickly derailed in 1863, the year of the next salon, when he had submitted the Déjeuner sur l’herbe, as you mentioned. And that year, there were quite a large number of refusals, and in a—

CUNO: Why was that? Why was that such a conservative salon year, 1863?

ALLAN: You know, I’m not entirely sure. It may have been a function of stricter regulations that year or the number of submissions. But you know, this was a kind of recurring problems and artists were disgruntled. And that year, in a kind of conciliatory, even reform-minded gesture, the emperor and the administration allowed for an exhibition of the refused works, which was quickly dubbed the Salon des Refusés.

And because it was dubbed that, you know, people came flocking to this exhibition, as if they were going to, like, a freak show. And Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe kind of reigned over that sort of unruly, beyond-the-pale display. And so it was not just the picture itself and its seeming violation of artistic decorum and flaunting of public morals, by showing very frankly a contemporary nude woman kind of picnicking with a couple of gentleman in bourgeois dress, in a kind of a fake, artificial landscape environment; it was also the context in which it was seen.

And that instantly made Manet this kind of notorious figure. And in the next two years, his submissions only kind of reinforced the sort of popular opinion of him as a provocateur and trouble maker. In 1864, for instance, he showed a picture of the Dead Christ with Angels, and that was seen to be a kind of a profanation of a sacrosanct subject. A lot of critics, you know, thought he treated Christ like it was just a body at the morgue. And then that was followed up by Olympia, in 1865, which was, to contemporary eyes, a shockingly vulgar kind of modern updating of the tradition of the nude, in a way that kind of violated all conventions of sort of idealizing beauty and that sort of thing.

There was so much public and critical outrage around that that Manet was kind of blackballed the next year. And so in 1866 his submissions were refused outright, and I think that was one of the things that prompted Zola’s initial defense of Manet. So it was sort of a moment of kind of maximum controversy in Manet’s career.

CUNO: And talk for a minute, if you can, about how this outrage was expressed. This critical reaction to Manet’s work wasn’t expressed only in word—that is, in the printed form in a newspaper—but also in image, by way of caricatures. And give us a sense of just how vitriolic the reaction was.

ALLAN: Oh, gosh. Some of the language that comes up in the criticism is really remarkable. You know, the Olympia was compared to, like, a gorilla, for instance. There was this cat with an arched back and tail upraised, and that was seen as a sign of kind of a displaced aggressive sexuality. There was this bouquet of flowers, which in some of the caricatures was implicitly identified with the woman’s genitalia. And there was this language of decay and putrescence and that kind of thing in the criticism.

You know, Manet famously sort of does away with halftones and he presents fairly strong juxtapositions of light and dark, with minimal indications of shadow. And some of the sort of indications of shadow were described as streaks of dirt and that kind of thing. So it was seen to be like a putrescent, dirty, kind of defiled, deeply sexually unwholesome kind of picture that offended both artistic decorum and public morals.

CUNO: And this wasn’t unique to Manet. I mean, there had been this long tradition—or at least decades long tradition—of caricatures of paintings and caricatures of people in galleries looking at paintings, and caricatures of artists, Daumier being one of the premier exponents of such caricature. But it was ratcheted up to such a degree in the 1860s with Manet.

ALLAN: Yeah. And I think there was a lot of crowd agitation at the salon, where I think, you know, they had to, like, have guards posted in front of the paintings. So there was a degree of sort of hysterical reaction around this picture, which was unusual and to some extent, unprecedented, I think.

CUNO: So in 1866, when Zola writes this defense of Manet, it is in a publication. But a year later, he publishes it as a standalone brochure, an independant brochure, a kind of book-length defense of Manet. In that defense of Manet, he imagines a scene where he comes across Manet in the street. And he sees ruffians throwing rocks at him, and then he says this. He says, “The art critics—I mean the police—are not doing their job well. They encourage the row, instead of calming it down, and even—may God forgive me—it looks as though the policemen themselves have enormous brickbats in their hands. Already it seems to me there is something decidedly unpleasant about this scene which saddens me. Me, a disinterested passerby, calm and unbiased.”

What was Zola’s career at this time? Because clearly, he’s got his own literary ambitions, and this is a vehicle for him to express those ambitions.

ALLAN: Well, I think that’s exactly right. And a lot of men of letters at the time in France do venture into art criticism as one way to sort of kickstart their careers. I mean, this is a— this is a moment where art criticism is a sort of a major journalistic genre. There’s many newspapers running big, long, serial reviews of the salon, with, you know, big readership. So it was an important public platform for a lot of aspiring writers.

Zola, as you mentioned, is just sort of beginning. He and his widowed mother had moved to Paris, I think in the late 1850s. And there were a couple years of sort of extreme poverty, and he needed to sort of find gainful employment. And he started out very modestly, as a clerk with the publisher Hachette. And as a kind of a sideline, he began freelancing as a journalist and working on fiction, as well.

And you know, since his childhood, he had, you know, written poetry and, you know, and some literature, so it wasn’t a new thing for him. And in 1865, the year of Manet’s Olympia, he published his first novel, which is a sort of slightly veiled, semi-autobiographical novel called The Confession of Claude. I haven’t read it, but apparently it was quite sordid and controversial, and drew police attention. So I think, you know, he was coming into conflict with the authorities and, you know, sees Manet coming into conflict with the authorities, and so there’s some affinity as this sort of more republican-minded, anti-establishment, anti-police state feeling there.

And in 1867, the year of his sort of reissue as pamphlet of his essay on Manet, he publishes Thérèse Raquin, which is his first really big novel, super controversial, a very sordid tale of a couple that, you know, perpetuates the murder. And then it’s the— how the relationship just sort of disintegrates in the aftermath of the murder. It was a hugely scandalous tale. And so, you know, he’s just kind of stepping out into the limelight as he’s writing these articles on Manet. And to some extent, I think it’s certainly disingenuous for him to pretend to be the calm, unbiased, neutral observer.

He’s really trying to capitalize on Manet’s notoriety, you know, to launch himself, to some extent. And it’s interesting, in the 1870s, when he’s well established as a novelist, you know, he’s not engaging in art criticism in the same way.

CUNO: Yeah. Well, in— with this defense of Manet in 1866 and then published as a pamphlet in 1867, Manet is very appreciative of this def— rising to the defense of his work, and he offers to paint Zola’s portrait. The painting that’s now in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. It’s a masterful portrait of a cultivated, scholarly young man. I mean, you wouldn’t know him to be an aspiring critic at the time. It looks as if he has made it fully and he’s a master in his craft. Describe the painting to us. And also, how Manet uses this portrait, not just as a favor for the young man, but as a kind of an aesthetic treatise on his own inspiration as an artist, with the Japanese prints in the background, the Spanish prints in the background, his own Olympia in the background.

ALLAN: Dissertations have been written on narrower subjects, but—[he laughs] It’s really interesting, this portrait. You know, just on the surface, I’ll describe it. And so we have Zola, a rather dandyish, elegantly-dressed Zola, in a black jacket and gray pants, seated in profile on a sort of plush embroidered chair. He’s seated at a desk, which is sort of littered with books, a big inkwell, a feather quill, an array of pamphlets.

CUNO: [over Allan] And even [inaudible] brochure. Yeah.

ALLAN: Yeah, exactly. And the foremost pamphlet has— You can read Manet. So that’s doubling his Manet signature for the painting, but it’s also an allusion to the pamphlet that Zola devoted to him. Zola’s sort of got one large volume open, which art historians have identified, or at least speculated, as a volume in a series on the history of European art.

So that in itself is interesting, because— We can talk about Zola’s image of Manet a little bit later, but one of the things he’s emphasizing is how Manet, to come into his own as an artist, is really putting aside the art of the museum and kind of moving past those outside influences. And here Zola is reading a history of European art, so there may be some sly response to Zola there.

Behind him on the left there’s a Japanese screen. And then kind of clustered together in a frame in the upper right, as you mentioned, there is a reproduction of Olympia, which for Zola, was Manet’s masterpiece and really encapsulated his artistic personality. Behind that is a reproduction of a painting, a famous painting by Velázquez. And then next to those two prints are this sort of wonderful Japanese print, which Zola invokes in comparison to Manet, in his text.

So certainly, Manet’s visual world and image world, things that were important to him as an artist are invoked here. But those are things that Zola is also attempting to minimize in his text. He wants to sort of separate Manet from Spanish art and from the art of the museums. So Manet is, in some sense, saying, no, these are actually important to me, and that my dialog with these things is deeply intrinsic to my practice.

CUNO: Well, in the— this 1867 defense of Manet’s work, Zola describes Manet as if he were writing his portrait of Manet. He says that, “Édouard Manet is of average height, more short than tall. His hair and beard are more chestnut. His eyes, which are narrow and deep-set, are full of life and youthful fire. His mouth is characteristic, thin and mobile and slightly mocking in the corners. The whole of his good-looking, irregular, and intelligent features proclaim a character both subtle and courageous, and a disdain for stupidity and banality. And if we leave his face for his person, we find in Édouard Manet a man of extreme amiability and exquisite politeness, with a distinguished manner and a sympathetic appearance.” Once again, you get a sense that Zola is using this defense of Manet as a kind of exercise for his own writing skills, his own ability to characterize and describe a person. But you also may see it as a kind of— kind of fawning account of Manet to encourage this relationship between Zola and Manet.

ALLAN: No, I think that’s exactly right. And he’s also, given the highly-charged, polemical context of the time, with all of these critics painting Manet as some kind of flame-throwing revolutionary, some kind of disheveled Bohemian crackpot, some jokester, trickster, who’s kind of staging these radical interventions in the salon— You know, by emphasizing his distinguished appearance, his sort of bourgeois background, his sartorial elegance, his intelligence, it’s a counter. It’s a counter portrait of Manet, given what’s been circulating in the press at the time.

CUNO: When writing about Manet at this time, Zola seems, I think, to use the opportunity to give his views on modern art as such. It’s almost as if he’s not just promoting his own ambitions as a writer, but that he’s positioning himself as a kind of leading art critic, and defending a kind of aesthetic. He says at one time, “Here, then, is what I believe concerning art.” And then he goes on to talk about it. Did Zola see his defense of Manet, do you think, as a kind of treatise on modern art, as something that would distinguish Zola himself as a writer on art from the predecessors like Baudelaire that would precede him? Is Zola making a case for his own art criticism?

ALLAN: I think absolutely, 100%, he’s doing that, and certainly distinguishing himself from forerunners like Baudelaire. In a lot of ways, we learn more about Zola’s ideas of modern art and, you know, what he would call naturalism, and about Zola himself and his sensibilities, than we do about Manet, in many respect in this text, which is why it’s so interesting. Just like with Manet’s portrait of Zola, we learn a lot about Manet. And you know, like they’re— these things are intermixed.

Maybe I should just lay out some of these basic ideas that he propounds in this text. He talks quite a bit about beauty. And he kind of sets up as a strawman, an academic notion of ideal beauty, the standard for which is kind the sculptural tradition of ancient Greek and Rome. And he lambastes this notion that art of the present needs to subordinate to this standard, this absolute ideal rooted in the ancient past.So he caricatures a kind of classicist notion of art.

And in opposition to that, he sees art as a rich, progressive unfolding. He calls it an epic of human creation. And the standard that he posits, as opposed to some ideal beauty, is nature, external reality. And the variable is the diversity of human beings, creative human beings. And so it’s the proliferating individual viewpoints that he celebrates. And so it’s this notion of extreme diversity. It’s a very relativist kind of notion of beauty and art.

And Manet, for Zola, represents the most individual, the most original of his time. And so he sees Manet as adding a new note to this unfolding epic of human creation. And so it’s a theory of kind of originality and individual— artistic individuality that he is propounding. And the story he tells about Manet is really a series of disavowals, of Manet kind of moving past the influence of his first teacher, Thomas Couture; of moving past the influence of older schools of European painting, Spanish art in particular, he mentions; and just kind of excluding all alien influence and arriving at this notion of sort of this pure nugget of Manet’s personality, unhindered by any outside influences.

And you know, he creates this scenario that’s like, it’s this artistic intelligence, this original temperament in the face of nature. And that’s the scenario that matters. You know, the artist, and really the eye of artist, you know, and really, like the physiology of the eye. Like, this is a very biological thing for Zola. It’s the flesh and blood of the artist, his sort of bodily constitution directly affecting how he sees the world and the visual facts he confronts and processes those and translates them into patches of color and painting.

So it’s in the end, a very empirical— kind of a radically empirical notion of art making, where he says, you know, unhindered by prejudice, education, previous culture, it’s the artist and the eye of the artist receiving visual information and processing it. And the end result is this kind of amazing formalist statement of painting, as just sort of an array of colors, patches of color, and Manet’s art being all about the relationships of tone and value and these patches of color.

So it’s really fascinating. And this had a big impact on the modernist notions of Manet’s art, where, you know, the subject matter didn’t mean anything, wasn’t important. He just treated everything like a still life, an arrangement of shapes and colors. And then scholarship since that moment has really been about reinscribing Manet’s art into all of the things that, you know, Zola excludes. And so we’re still kind of dealing with that legacy of Zola and the scholarship on Manet today, where it’s like, well, his dialog with the art in museums is actually really important. You can’t just, like, shunt that to the side. So—

CUNO: We do have letters between Baudelaire and Manet, and that is, both from Baudelaire, an earlier friend of Manet’s, and from Manet, one to the other. And in a letter to Baudelaire from Manet in 1863, Manet writes, “I would really like to have you here, my dear Baudelaire. They’re raining insults on me. I’ve never been led such a dance.” To which Baudelaire now— This is the interesting thing, because we can’t imagine Zola writing something like this. Baudelaire responds quite differently than Zola.

He says, “So once again, I’m obliged to speak to you about yourself and must do my best to demonstrate to you your own value. What you ask for is truly stupid. People are making fun of you; pleasantries set you on edge; no one does you justice, et cetera, et cetera. Do you think you are the first to be placed in this position?” This kind of sense of poking fun, pushing Manet away thinking you’re just too sensitive. You gotta live with this stuff. If you’re gonna be an artist and you really believe in what you’re doing, do it and don’t be dragged back to something else because of the way the critics respond to you. This kind of frankness that the older Baudelaire, longer the friend of Manet than Zola— You wouldn’t find that in Zola’s writing.

ALLAN: Well, and Baudelaire was, you know, raked over the coals in, you know, a true legal sense, when he published Fleurs du mal. Like, he faced real, like, sort of legal censorship and, you know, got into real trouble in a way that Manet never did with his paintings. So Baudelaire was like, okay, you know.

CUNO: I’ve done it before.

ALLAN: Don’t exaggerate, you know? I’ve seen a lot worse.

CUNO: Because Zola praised Manet’s formal inventiveness, as you described it, shortly thereafter. And he says, “One’s first impression of a picture by Édouard Manet is that it’s a trifle hard. One is not accustomed to seeing reproductions of reality so simplified and so sincere. But as I’ve said, they possess a certain stiff but surprising elegance.” This kind of language and this kind of interest in the aspect of Manet’s paintings, you wouldn’t find Baudelaire on that. Baudelaire would be pushing the artist to be individually inventive, but wouldn’t be responding to the kind of formal character of the paintings.

So is it fair to see that Manet’s work is evolving from one generation, as it were, to the next? That is, from Baudelaire to Zola? So that Baudelaire was a champion of his early dark paintings, those Spanish paintings; and then Zola is a champion of the later paintings, of the later sixties and into the seventies?

ALLAN: Yeah. This is a tricky question. I mean, art historians always wish that Baudelaire actually, you know, devoted some art criticism to Manet. But there was a bit of a generational mismatch there. Most of Baudelaire’s art criticism was sort of written—

CUNO: In the forties, probably.

ALLAN: Ju— and the fifties.

CUNO: Yeah.

ALLAN: And his famous essay, “The Painter of Modern Life,” I can’t remember when it first appeared. It was eventually kind of reissued, in 1863; but it had been written a little bit earlier. So Manet was really just beginning when Baudelaire was kind of at the end of his career as a critic. And Baudelaire is most famous for his championing of Delacroix and that, you know. So there is that romantic aspect. And then art historians also, you know, wish that Baudelaire had devoted “The Painter of Modern Life” to Manet, as opposed to the minor illustrator, Constantin Guys.

But Manet loved Constantin Guys, collected him, and I think in a lot of ways, aspired to that moniker of the painter of modern life, over the course of his career. And so Baudelaire, you know, Baudelaire dies in 1867— And, you know, he had suffered a horrible stroke in 1866. So when Zola is stepping in, that’s the exact moment where Baudelaire is really on his way out. And so there’s a way that Zola could kind of insert himself, identify himself with Manet, and kind of wrench Manet away from that earlier association with Baudelaire. So the timing is critical there. But Manet, you know, remains, I think, very faithful to Baudelaire’s memory.

In the 1870s, famously, he has a relationship with the poet Stéphane Mallarmé. They become very good friends. And both Manet and Mallarmé are, in some ways, caretakers of Baudelaire’s memory. They collaborate on a sort of deluxe edition of Mallarmé’s translation after Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven. Manet contributes illustrations. So it’s a interesting dialog between Manet, Mallarmé, and Edgar Allan Poe. But Baudelaire is in the mix, too, because Baudelaire was the great champion of Edgar Allan Poe in France, and had translated short stories and what have you. And so Mallarmé was definitely continuing in that tradition. And I imagine they must’ve talked about Baudelaire all the time.

And in 1880, Manet has a solo show in this gallery called La Vie Moderne, Modern Life. And what does he show in that exhibition? He shows a portrait of Constantin Guys.

CUNO: Oh, really?

ALLAN: You know? Yeah. And it’s fantastic. It’s a pastel portrait. You know, Constantin Guys is an old man at that time. And so Manet is really, you know, in the context of the gallery of modern life, you know, advertising his sort of affiliation with Baudelaire, through that portrait of Constantin Guys.

But he also shows a portrait of Zola’s wife in that show. And that’s a moment where Manet is busy reading Zola’s latest naturalist novels, Nana, The Belly of Paris, all of these great novels, and is very supportive of Zola’s literary career. I think he gobbles up these books. He really enjoys them. And they inform his own notion of modern painting and attending to the contemporary Paris and the social life of Paris in the cafés and what have you. And critics of the time certainly associated Manet with that kind of project of portraying modern life that was Zola’s project, but also Baudelaire’s project, in different ways.

CUNO: So you mention 1880 and the exhibition. Three years later, 1883, Manet dies. And Zola writes of him in a catalog of a memorial exhibition in the year 1884. He says, “He gave up his whole life to his task. And none of us who knew him well ever dreamed of wishing him to be more balanced or more perfect. For had this been the case, he would certainly have lost most of his originality, that sharp light, that exact sense of values, and that vibrant quality which distinguishes his pictures from all others.” Tell us about Manet’s standing at the end of his life, that would lead, then, to this memorial exhibition, this kind of crowning achievement, in 1884.

ALLAN: Things are definitely changing for Manet in— on a number of fronts. First, like, as kind of deep background, there’s a big political shift. I mean, the Second Empire, where Manet, you know, came into so much conflict with the sort of authorities in the salon, that ended with the Franco-Prussian War. And then subsequently, the Paris Commune and the Third Republic is established. And by the end of the 1870s, after some trial and tribulation, a pretty solid center-left government is established, and Manet’s political sympathies are fairly inline with this new regime.

And so he has a kind of a different relationship with the official establishment in the last four or five years of his life. And in fact, an old childhood friend, Antonin Proust, who ends up being Manet’s first kind of real biographer, is a politician, a Republican politician. He’s a deputy in the Chamber of Deputies. And then he eventually becomes Minister of Fine Arts, in the short-lived government of Léon Gambetta.

And because of Proust’s power, Manet gets the Legion of Honor at the end of 1881. And it’s really Proust who is able to orchestrate this posthumous retrospective, at the École des Beaux-Arts. You know, this sort of bastion of academic values. And at the same time that there was this political shift, the salon was liberalizing, the regulations were loosening up a little bit, and eventually the state relinquishes control of the salon and the artists are in charge. And all of this prepares the way for Manet getting a salon medal, the first official award he gets in the salon since that honorable mention I mentioned at the beginning, in 1861, for The Spanish Singer.

So it’s his first official awards in twenty years. And you know, Manet is, like, well into middle age at this point. And the Impressionists have been exhibiting outside the salon since 1874, and they’re the new radicals. And they, you know, almost by default, position Manet closer to the artistic center and conservative critics are praising Manet for sticking to the salon.

The critical tide is turning, as well. Manet’s still controversial, a lot of critics are not convinced; but they do take him more seriously. The temperature of the discourse is—has gone down. And there’s a, you know, an uptick in his market, as well. All these sophisticated guys are buying, like, flower paintings from him. He becomes friends with Charles Ephrussi, who is, you know, a critic writing for the Gazette des Beaux-Arts, which is not the most kind of avant-garde journal.

So he’s getting some fairly posh collectors coming to his studio, he’s getting new support in the sort of realm of the haute bourgeoisie. Zola’s publisher, Charpentier, he and his wife host a major salon, you know, a very high-profile salon in Paris, and Manet is part of that circle. And it’s the Charpentiers who start this journal La Vie Moderne and set up the gallery as affiliated with the journal, that gives Manet this solo show. And the Charpentiers have a lot of social power and that, you know, works to Manet’s benefit, as well.

So things are turning in his favor career-wise, but his health is declining rapidly. And he has a sort of a syphilitic condition, which, you know, we usually refer to as locomotor ataxia. It’s kind of a nervous condition that has a debilitating effect on his mobility in his legs. So his mobility is increasingly restricted over the years, from like, 1879, ’80, to the end of his life in 1883, and he has to kind of remove himself from Paris every summer to kind of pursue various courses of treatment and rest cures and that kind of thing.

And as his health declined, his production is affected. He’s not doing the big Déjeuner sur l’herbe type pictures anymore; he’s sort of focusing on smaller-scale work. He’s doing little watercolors, he’s doing pastels, he’s doing flower paintings that he can paint, you know, while seated, small-scale canvases; but you know, working really brilliantly in these genres. So a lot of things changing for Manet in those last years.

CUNO: Well, it’s a perfect Segway to our next biography—that is, of van Gogh—because as Manet dies in 1883, van Gogh comes to Paris at about that same time, and the new generation emerges, of which he’s an important part. In this book, the biographical text of van Gogh is written by his sister-in-law, Jo van Gogh-Bonger. Jo was briefly married to Vincent’s brother Theo, who died two years into their marriage. With Theo’s death, Jo inherited 364 paintings by Vincent van Gogh, plus a large number of drawings and letters.

And she became his kind of champion, he having had little success, of course, in his lifetime. So in 1905, she organizes a large and quite influential exhibition of van Gogh’s work at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, the principal city museum in Amsterdam. And in 1913, she publishes this biography. So much of what we know about the inner life of van Gogh, we know because of her biography and what she includes in it. I have to say, this is the first time I had read this biography. Is it your first time, too?

ALLAN: It is. And I found it fascinating and quite moving.

CUNO: Yeah. I wonder why it is that we haven’t read it before, because we go straight to the letters, and the letters supersede then this early biography?

ALLAN: I think that could be it. And I mean, just me personally, I haven’t done any big research project on van Gogh, so I haven’t immersed myself in the literature, the way I have with some other artists. I’ve read some other more recent biographies, very deeply-researched ones, and I’ve read a lot of the letters. But I think you’re right; we go to the letters.

CUNO: Yeah. So she writes sensitively, Jo does, the sister-in-law of Vincent— sensitively of Vincent’s London years and how worried his parents were of his growing disinterest in his job with the art dealer Goupil, and of their suspicions that the London fog might be depressing him. There’re any number of letters that she quotes from the parents, about their concern for the son. And it’s kind of aching to read them.

She quotes Vincent also writing to his parents, “It seems as if something were threating me.” And she wrote of the dark period, “With the force of despair, he clung to religion, in which he tried to satisfy his craving for beauty, as well as his longing to live for others.”

We should acknowledge that his father was a man of the cloth, was a parson. So he was raised in that family and in that framework. But these letters that she’s referring to both from Vincent himself and from the family, are just so nakedly presented in this that it’s quite surprising.

Give us a sense, though, of van Gogh’s early years now, and how important to him was this relationship to his family, and to his father in particular, as maybe kind of role model for him as a parson.

ALLAN: I mean, what’s striking to me is the struggle for identifying vocation and finding his path, and the number of false starts and disappointments, and the amount of moving around, like from city to city and place to place. Like, the sense of restlessness and rootlessness and really searching for kind of an identity and a meaningful vocation.

And, you know, there are two main lines of work in the family: art dealing— His uncle, also named Vincent, works for the, at that point fairly international, trans-European firm, Goupil, which had an important branch in the Hague, as well as, like, in London and in Paris and other places. And so he embarks on a career in the Goupil firm, initially.

CUNO: Vincent does.

ALLAN: Vincent—

CUNO: Theo was already there, or he comes later to Goupil?

ALLAN: Theo’s younger and comes after Vincent, but they both begin their careers in the— in the Goupil firm. And Vincent, you know, starts in the Hague. He goes to the London office, and eventually, the Paris office. And you know, initially he’s, I think, seemed to show some promise as an apprentice in the business. But something seems to have happened in London.

You’re mentioning the letters and I think he was really experiencing a lot of social isolation, is the sense I get from Jo’s account. And so, like, there was some depression creeping in, and some of the personal eccentricities that she describes, you know, kind of manifesting themselves. And so it seems like that’s the first time his parents really start to worry about him. And then after, like, that career kind of derails in Paris, he’s sort of becoming, with his sort of problems with depression and social isolation, the religious fervor kind of increases, to the point where it’s not good for businessHe doesn’t have the right personality profile to be a wheeler-dealer in the art world. You know, very worldly kind of business, and he’s got all these, like, religious feelings.

And so he abandons that career, and then resolves to become a minister. And that, you know, despite his religious convictions, there are personality issues that derail that plan of action, too. I think he initially intends to pursue a pretty rigorous course of theological studies, a course of studies several years long. But he’s not suited to the rigors of student life. And so he resolves instead to become a kind of a preaching lay preacher-evangelist. And he can go on just a three-month course in Brussels to do that. But he even struggles with that course and that line of work, and he ends up sort of in mining country in Brussels, as a preacher. But you know, there’s a tendency to extremity in his personal behavior and I think he sort of— he ends up living in some, like, hovel, and just kind of scaring and alienating people. So that the committee that runs the evangelical outfit, they don’t want to have much to do with him.

And so it’s just— I mean, it’s this kind of sad chronicle of disappointments and, you know, struggles to find his way, both professionally and then personally, too. There are these, you know, moments of heartbreak, where he’s disappointed in love, which, you know, plunge him into, you know, more depression and despair and— It’s hard to read. And then eventually, you know, art is the thing and he throws himself into that, and that’s what sticks.

CUNO: Well, in Jo’s account, it’s interesting not only what she tells us from her point of view, but what is found in the letters, as we’ve said, but also various other accounts. She quotes not only letters from the family and letters from Vincent himself, but accounts, in one case, of one of his teachers that appeared in a newspaper, a teacher in Classical languages, a man named Dr. Mendes da Costa. And he says that this teacher recorded many characteristic particulars, Vincent’s nervous, strange appearance that yet, was not without charm; his fervent intention to study well; his peculiar habit of self-discipline, self-chastisement, which is extremely [inaudible]. So self-discipline and self-chastisement.

And finally, his total unfitness for regular study. This kind of laying bare the strange, peculiar habits of the man, the kind of weakness of the man, and the sense that even this kind of self-chastisement and self-discipline, as if there is a kind of physical punishment [Allan: Yeah] that he inflicted on himself.

ALLAN: Yeah, I think— I mean, there’s many sides to Vincent that come out in Jo’s text. And on one side, the— sort of the more positive side, as it were, there’s a really acute sort of social conscience and a great love of nature, a real sympathy for the poor. Like, he has these Christian impulses, right? These kind of charitable impulses. He wants to do good, he wants to have a positive impact on the world.

And then there are these more debilitating negative traits that kind of derail his ambitions on the most positive side. And like, he sort of seems to be a kind of irascible, irritable figure. There’s a lot of nervous agitation. There’s a tendency to go to extremes, this kind of zealousness in whatever it might be, that sort of freaks people out and alienates people. There’s sympathy and there’s a lot of support and love from his family, at least as Jo says it; a lot of forbearance and, like, really trying to accommodate him and to encourage him and to support him in whatever way they can.

But then there’s also this despair. It’s sort of like Vincent’s his own worst enemy and—

CUNO: [over Allan] Yeah. How strange do you think it was to publish it, this— to lay bare this weak— these weak moments of this man and the pain he caused himself and his family and his friends? I mean, this is the early twentieth century now, so it almost seems as if it’s a kind of burgeoning psychological study of a person, with a kind of intimacy that you wouldn’t have found before now.

ALLAN: No, I think that’s right. I mean, we have to remember that the text was first published as a preface to an edition of the letters. And—

CUNO: The first volume of the letters.

ALLAN: Yeah, in 1913

CUNO: Right.

ALLAN: And there’s nothing more intimate than those letters. You know, just letter after letter of, like, Vincent’s, you know, what’s going on in his head. So I think this text, to some extent, is there in that context to kind of contextualize and comment, to some degree, on the letters that follow, to kind of an overall picture of the life.

So I think it’s partly explained by that. But also, like, by this point, there’s a tradition of—you know, since the Romantic era—of kind of intimate biography. And in fact, if we think about some of Vincent’s artistic heroes, like Jean-François Millet, the famous painter of peasant life associated with the Barbizon School in France— There’s a biography of Millet by this man named Alfred Sensier, who also wrote a biography of Théodore Rousseau, another Barbizon School artist that Vincent loved.

And those are pretty intimate biographies, with letters and interestingly, those biographies also played a big role in marketing that work. And so you get the beginnings of a kind of expressive paradigm, where the art really is expressive of the life. And by establishing a kind of biographical ground for appreciating the art, you know, you can read the artist’s pain and suffering through the art.

And that definitely kind of preprogrammed, I think, the response to Vincent’s art through most of the twentieth century. And it’s hard to even escape the biography today, when talking about Vincent. I mean, it’s what we mostly talk about.

CUNO: Yeah. You mentioned that he lived in the house of a miner in Belgium. And there, he writes home. He says, “My only anxiety is, how can I be of use? Can I serve some purpose and be of any good?” And then later, not long after that, he writes about art as perhaps that way of doing some good in the world. He says, “And in a picture, I want to say something as comforting as music is comforting. I will do so with my drawing. From that moment, everything has seemed transformed for me.”

And Jo says of this that it sounded like a cry of deliverance, his finding himself in art. Do you think that was just a romantic view of this pain that he was going through, when he was making a statement like that?

ALLAN: That’s a statement of his conviction, I think. That seems pretty genuine to me. I mean, he really threw himself into what he did. And you know, the interesting thing for me is, like, this idea that his art would be consoling or comforting or that he wanted that; but when we look at it, there’s— That nervous agitation is what we see more than anything. That—

CUNO: [over Allan] Yeah. It’s like he put that onto the painted canvas. So the torment that he suffered internally he rendered it externally.

ALLAN: It’s also like he did find that when he was working, when he was absorbed in work and the painting, that was also a way to forget some of the more troubling personal things going on. And so there’s a way that the art, you know, kind of saved him from himself, as well.

CUNO: Right. Now, Theo plays a big part in this when he does sort of— finds himself as a painter. He says that anything that’s probably positive, they want to encourage him, this anxious young man. So Theo introduces him to a painter, a man I’d never heard of, van Rappard, who was a rather wealthy man. And the friendship lasted about five years, and then something happened.

Jo quotes form a letter van Rappard wrote to Vincent’s parents, saying, “Whenever in the future, I shall remember that time. And it was always a delight, a delight for me to recall the past. The characteristic figure of Vincent will appear to me in such a melancholy but clear light. The struggling and wrestling, fanatic, gloomy Vincent, who used to flare up so often, was so irritable, but who could still deserved friendship and admiration for his noble mind and high artistic qualities.”

So Vincent goes from a miner to an artist. And both the miner and the artist, those are situations that are not very profitable. But he’s now convinced that he wants to be a painter. And Theo encourages him to come to Paris.

What do we know about Theo’s career at that time? We know he had his own gallery on the Boulevard Montmartre. And he was in contact and he was trying to sell Monet and Sisley and Pissarro and Seurat and Degas and so forth. Was he in a state to really help Vincent at that time, to provide him the kind of personal and financial resources necessary to get through life?

ALLAN: Theo, you know, he really took to art dealing, and as far as I understand, was fairly successful. I mean, he started, I think, in the early 1870s, with the Goupil firm. In the Hague, I believe, he began. And then kind of also kind of cycled through some of the branches, and ended up in the main office in Paris. So that, you know, gives some idea of his standing in the firm. He kind of rose up pretty quickly. And the Goupil firm became, in the 1880s, it became Boussod, Valadon & Company. That was the name of the successor firm. And I think Theo’s gallery in Montmartre was sort of a branch gallery of Boussod, Valadon & Company.

And Theo kind of represented, I guess, the sort of vanguard of dealing within that firm. And it’s an interesting moment, because 1886, ’87, the kind of period we’re talking about, the Goupil firm, or Boussod, Valadon Company, is shifting its stock away from some of the academic salon favorites that they made their reputation on earlier. They had kind of ventured into Barbizon School stuff in the 1870s and early 1880s, and now they were testing their waters with Impressionism and things like that. And by that point, artists like Monet are fairly well established and, you know, high-end dealers like Georges Petit are showing Monet in Paris. And the Boussod, Valadon firm was kind of trying to set itself up as a competitor of firms like Durand-Ruel and Goupil, and Theo was part of that initiative.

But there’re stories that on the ground floor of this gallery, he showed, you know, some of the more conservative stuff; and then for receptive clients, he would take them upstairs to show the latest in the avant-garde material. So yeah, he was doing a lot, you know, personally to promote that stuff. And I think there was some friction with the bosses in the main office about his promotion of that material.

CUNO: So Theo’s busy at work trying to make a go of his own life and his own career, and Vincent’s away back in the apartment or the house, painting away like this, but he’s getting more and more agitated. The winter’s coming on; it’s getting cold. So he leaves Paris and he goes to the South of France. And in the South of France, he’s got this idea he’s going to create another life for himself. But through Theo, Gauguin learns that Vincent is in the South of France, and makes a connection then with Vincent, and Vincent approaches him to come to join him in Arles. What was Gauguin’s career like at that time, and what did it mean for him to pick up sticks and to move to the South of France, to join with this kind of frightful character?

ALLAN: Yeah, this was kind of a recipe for disaster. There’s so many ways, I think, they were opposites and— So Vincent was really invested in notions of artistic community and fellowship. He had this very, like, sentimental, idealistic notion of being part of a brotherhood of artists working in the South of France. And he kind of procured this house in Arles, which today, we refer to famously as the yellow house. And he so earnestly went to work preparing this house for Gauguin’s arrival, decorating it and painting it and—You know, this is gonna be your room and this is gonna be my room and— If you’ve ever seen diagrams or floorplans of this house, it was a tiny space. Like, they’d be living really on top of each other.

And then Gauguin comes down like—he just— It’s not because he dreams of artistic brotherhood with Vincent van Gogh; it’s just he’s totally down on his luck. He’s totally broke. It’s really, like, financially expedient. But he still takes some convincing. Theo kind of really, I think, twists his arm because van Gogh’s sort of begging and pleading. And so he comes down, somewhat reluctantly.

And then, you know, in terms of their vision of art, I mean, they’re really at loggerheads. And so I think they get into all these fights about art making. You know, Vincent is all about working from nature. You know, in an expressive way, but you know, landscapes and birds’ nests and flowers and—Gauguin, it’s like the memory and imagination is much more important. He has this kind of what we would call symbolist inclinations. And there’re some fundamental disagreements about their approach to art making, which kind of exacerbates things. And I think just it, you know, ended up, like, just amplifying Vincent’s sort of nervous condition. And you know, then there’s this famous episode of the cutting of the ear and Gauguin is ter— you know, terrified of him, you know.

CUNO: Yeah. And it’s he who has to wire Theo to tell him that this had happened, that Vincent’s in the hospital because he’s done this. And he writes of Vincent at the time, he says, “It’s impossible for him to associate with people in any indifferent way. It’s difficult even for those who are his best friends to remain on good terms with him, and he spares nobody’s feelings.” That’s a hard thing to read, when you’re miles away from your beloved brother.

ALLAN: And you know, Gauguin is sort of famously a pretty, like, selfish, cool-headed kinda guy. You can just imagine—

CUNO: Ambitious.

ALLAN: Ambitious, self-serving. But you know, but pretty cool. And so I think just, when you think about Vincent and his sort of nervous agitation and Gauguin, it must’ve been sort of this really oppressive kind of situation.

CUNO: So Vincent then returns to Paris and he travels on to Auvers, where he painted the famous portrait of a man he was close to, Dr. Gachet. And two months later, in July, he shoots himself, and he dies two days later. What were Vincent’s last months and days like, then, in Auvers, where he was in some isolation, or at least certainly away from his painter friends and away from his brother?

ALLAN: Well, according to Jo’s account, things were, in some ways, looking up for Vincent. He had previously been in an asylum in Saint-Remy, not far from Arles, in the South of France. And Vincent basically committed himself there. He didn’t sort of trust himself to be alone anymore and he feared the next kind of mental crisis. And that, from Jo’s perspective, seemed to have been somewhat good for him, because when he arrived in Auvers, like, she wasn’t expecting him to seem so sort of healthy and robust, and seeming to be in sort of good possession of himself.

So being in the asylum, with that sort of—the medical supervision and the regular meals, the routine of work, like, that seemed to work to his benefit. And so when he arrived in Auvers, he seemed to be in good shape. And I think part of the reason Theo helped arrange for him to come there is because Auvers sort of was not far from Paris. It’s a— it’s an easy trip into Paris. So he’s close, but not too close.

And he’s in a congenial sort of rural, semi-rural environment that could be productive for his painting. And it was a very productive time for Vincent, those last months in Auvers. There’re all these great pictures of the village, these little cottages with thatched roofs that he painted, with the really expressive lines, and the surrounding countryside, with the rolling hills and the pasture land and that kind of thingHe produced a lot. Some really, really great paintings, and the— this famous portrait of Dr. Gachet, who was well known in artistic circles. Was a good friend of Pissarro, for instance, known as a homeopathic doctor. And it seems that Vincent and he had a— had a pretty close relationship. So he had some fellowship there, some support.

And things were starting to turn for him career-wise, too. I mean, in the beginning of 1890, this critic, Albert Aurier was quite influential. Wrote a very important and influential appreciation of van Gogh, which appeared in the Mercure de France. And later that year, his art was shown at Les Vingt, which was this avant-garde artists association in Brussels. They would invite artists—you know, kind of progressive artists from around Europe—to exhibit work there. And Vincent’s submission— I can’t remember what he showed, but you know, a picture was actually purchased at that exhibition, and there was some, you know, really positive response. So there— Like, he was starting to get the recognition.

And so in some ways, his end, you know, was sort of abrupt and a surprise. And they didn’t really see it coming, necessarily. There was always the fear of a recurring episode, because you know, these were happening with increasing frequency, since the ear-cutting episode. And apparently, Vincent himself was very fearful of, you know, the next episode. So that kind of cast a dark shadow over things.

CUNO: Well, not long afterwards, after his death, Theo dies. And Theo is buried in Utrecht, Vincent in Auvers. But then twenty-three years later, in 1914, Jo moves Theo’s body to Auvers, so that it could be interred next to Vincent’s, in a kind of dramatic, rather a charming, I guess you could say, gesture. What do you think about this reburial of Theo, moving the body and interring it next to his brother and creating this kind of memorial plot for them?

ALLAN: Well, I mean, they’re obviously, you know, two really intertwined figures. I mean, Vincent’s whole career was enabled by Theo’s support. Theo was by far, the main correspondent, like really, the only lifeline that Vincent had. And so in presenting and preserving the sort of legacy of van Gogh the painter, that was also Jo promoting the legacy of Theo. And certainly, I think in the popular imagination, you know, we sort of think of them as a duo.

But like you said, it’s kind of a poetic gesture, too, because it gives Vincent that kind of fraternity, that, you know, togetherness that was so hard to sort of manage and achieve during life, you know? Like, Theo was, you know, unstinting in his support, but even admitted, like, it was really, really hard to live with van Gogh. But you know, in death, maybe they can be together in peace, you know? So there’s some—

CUNO: [over Allan] Right, right, yeah.

01:07:35:28 ALLAN: There was some aspect of that.

CUNO: Well, in these two biographical accounts, Zola’s of Manet and Jo’s of Vincent, we have two very different ways of writing about artists: this kind of dispassionate champion that Zola was of Manet’s work; and there’s this kind of al— not quite pathetic, but certainly there’s pathos involved in the accounting for the life of van Gogh. And there’s twenty and thirty years difference between the two, but they are extremely interesting and profoundly moving accounts of these two lives. And I want to thank you for the time you’ve given us today, Scott, to go through these accounts and to help us understand their role they play in telling us about and elevating the stature of the works of Manet and van Gogh.

ALLAN: Well, thank you, Jim. It’s a pleasure.

CUNO: Our theme music comes from “The Dharma at Big Sur,” composed by John Adams for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003. It is licensed with permission from Hendon Music. Look for new episodes of Art and Ideas every other Wednesday. Subscribe on Apple Podcasts or Google Play Music. For photos, transcripts, and other resources, visit getty.edu/podcasts. Thanks for listening.

JAMES CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, President of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art & Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

SCOTT ALLAN: Manet, for Zola, represents the most individual, the most original of his time. A...

Music Credits

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.