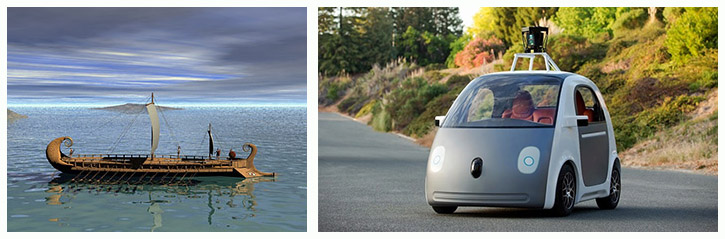

Can the origin of Google’s self-driving cars be found in Homer’s Odyssey? Edith Hall thinks so. The prominent British classicist and author of 20 books, who will be giving a free lecture at the Getty Villa this month, recently blogged about the Odyssey’s self-steering, intelligent Phaeacian ships as a possible precedent. She noted that the concept of robots is actually found in the Iliad, when the god Hephaestus built metal automatons to work for him.

Hall has a keen talent for drawing lively and provocative connections between contemporary life and the ancient world. She demonstrates the durability of myths and stories from antiquity by nimbly linking them to current events, pop culture, and the thorny social and political issues of our day.

Invited by the Villa Council, Hall will speak at the Getty Villa on June 28 on “Conflict Resolution and its Discontents in Classical Athens,” examining the difficulties of conflict resolution through a close reading of Aeschylus’s drama Eumenides.

Before she flew across the world to speak at the Getty’s contemporary rendition of an ancient Roman villa, we asked her a few questions.

Edith Hall. Photograph © Michael Wharley

Lyra Kilston: Your passion for the culture and literature of the ancient world is evident in your prolific career of teaching, writing, and lecturing. What first sparked this interest?

Edith Hall: My father is an Anglican minister (this would be called Episcopalian in the U.S.) and so Greek texts, as in New Testament Greek, were actually lying around our house. I liked the strange alphabet, even though my own interests have gravitated toward the pre-Christian, pagan Greeks and their philosophy. I also watched the movie Jason and the Argonauts (1963, directed by Don Chaffey) with the legendary special effects, pathbreaking in their time, by Ray Harryhausen. I simply couldn’t imagine anything more wonderful than a story about love and seafaring with glamorous gods playing with human’s fates from amidst the clouds.

You’ve found fascinating links between ancient and contemporary culture in many fields—politics, gender, justice, class struggles, slavery, technology and even science fiction. Can we find ancient precedents for every facet of modern culture?

Pagan ancient Greek and Roman civilization reigned for two thousand years. People who spoke Greek and Latin lived in tiny rural villages and great stone-built metropolises, from the Sahara to Scotland and Portugal to the Ganges. They built great universities, libraries, and temples; they administered enormous armies; they invented complicated political constitutions and elaborate legal codes. It’s hardly surprising that their texts record so many experiences that foreshadow modern history and so many moral questions we still face today. I am sure there are events in the modern world which would not remind us of something done or said in antiquity, but I’ve never been at a loss so far!

For your talk at the Getty Villa, you discuss the first example of a judicial, as opposed to vengeful, resolution for a major conflict, as described in Eumenides. But you point out that a legal judgment is not without its problems. There are many contemporary examples, but which ones are at the forefront of your mind?

The usual: Greece v. EU financiers; inhabitants of Ferguson v. the police; everywhere in the Middle East; Ukraine/Russia; indigenous peoples of the rain forests versus corporate capital. I think that western and imperial powers still don’t understand just how insensitive they sound when patronizing peoples they have historically oppressed. They could make the same points and arguments so much better with more sensitivity to history.

You’ve been a strong advocate for the study of ancient history in the British school system (which, like the United States, is experiencing a shrinking of the humanities curriculum). Can you speak about your vision of how you’d like to see ancient history fit into 21st-century education?

I think that classics has in some ways been its own worst enemy by overemphasizing the linguistic element—acquisition of Latin and ancient Greek grammar and syntax—over a broader understanding of ancient history and civilization. Schools can’t afford specialist teachers of the languages, at least not schools in the public sector, by and large, either in the UK or the United States. But why should that mean that we deprive our young of the magnificent thought and history of the Romans and especially the Greeks?

Thomas Jefferson said that the one true goal of school education in a democracy was to enable people to defend their liberty, and in order to do that they needed to know the political history of the world. To stay free also requires comparison of constitutions, fearlessness about change, critical, lateral and relativist thinking, advanced epistemological skills in source criticism, and the ability to argue cogently.

Papyrus fragment with text from Homer’s Odyssey, 1st century BC. The J. Paul Getty Museum

Whom else would one turn to for these but the Greeks? Writings in Greek are the best that the world has ever produced in a single language, including English, Sanskrit, Hebrew, Arabic, Chinese, German, French, and Latin. The ancient Greeks pioneered many of the genres and tones of voice in which we express ourselves—lyric, novelistic, tragic, comic, satiric, legal, medical, historiographical, biographic, philosophical. The 50-plus major authors writing in Greek made scientific discoveries, experienced historical crises, and debated philosophical quandaries of direct relevance to our own; sometimes they got it right (the idea that art needs to enlighten as well as delight); sometimes they got it wrong (slavery).

They developed skills that could advantage every modern citizen: the science of rhetoric or effective communication; the formula for making decisions in a way that maximizes the chances of the decision being a good one; the Aristotelian notion that crimes of omission can have even worse effects than crimes of commission; the accountability of those who would govern us; the idea that learning from the past can help humans avoid repeating mistakes; an inclusive approach to other ethnic groups’ gods; the discipline of utopian thinking—constructive imagining of what a fairer, better society and environment might look like.

Above all, the Greeks were politicized, beginning with the humans who were, from their first appearance in Hesiod, contending with the gods at Mecone in the northeast Peloponnese. The verb here, ekrinonto, is both problematic and astonishing. It is problematic because it encompasses a range of meanings in English. It could, with equal legitimacy, be translated “were distinguishing themselves from each other” or “were coming to a legal settlement of a dispute.” But both gods and mortals are involved in determining their relative positions. They are both agents of the identical verb. Their relationship is astonishingly balanced and it is conflicted. Through Prometheus’s theft of fire, Xenophanes’s atheism, Aristophanes’s subjection of Cleon to comic accountability, and Haemon’s Protagorean appeal to Creon in Antigone, the Greeks relentlessly questioned authority and dogma.

But in short, I would like to teach every young person, in translation, some bits of Homer, Greek drama, Plato, Aristotle, Livy and Tacitus. The world would be a better place.

Text of this post © J. Paul Getty Trust. All rights reserved.

Perhaps best summarized by Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr (roughly translated), “The more things change, the more they remain the same.” Or as my dear, departed mother often cited, “There’s nothing new under the sun.”