A long lively stroke of deep brilliant blue, black, and white, a curved swipe of muted yellow, a short dab of red—perhaps you’ve seen artist Roy Lichtenstein’s colorful painted aluminum sculpture Three Brushstrokes on a visit to the Getty Center. Until recently, it resided on the Plaza in front of the Getty Research Institute.

Three Brushstrokes, made in 1984, consists of three “strokes” of pure color frozen in space, rising to a height of more than ten feet—definitely an attention-getter. Each brushstroke is a fully realized three-dimensional form that playfully allows viewers to experience a stroke of paint from different vantage points.

Pre-conservation view of Lichtenstein's Three Brushstrokes (1984) as installed in front of the Getty Research Institute. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2005.111. Gift of Fran and Ray Stark. © Estate of Roy Lichtenstein

Gifted to the Museum by Fran and Ray Stark through the Ray Stark Revocable Trust in 2005, the artwork was on view at the Getty Center since that time. But as with most outdoor sculpture, the Southern California climate affected the work.

In this case, however, the answers to the critical questions needed to undertake conservation of the work haven’t come easy. The coatings on Three Brushstrokes are actually layers of industrial paint, including epoxy primer and polyurethane, typically found on automobiles. In time, these coatings start to break down, colors fade, the paint starts to flake, chalk or blister, and failure ultimately leads to corrosion of the metal underneath—a more problematic issue. Normally, Getty conservators would simply stabilize these types of issues with ongoing maintenance, but with the symptoms persisting, a full restoration recently became imperative for Three Brushstrokes.

And that kind of restoration calls for some extensive investigative research.

Three Brushstrokes is actually a unique early example of Lichtenstein’s work because it still retains some of the original paintbrush strokes, hidden underneath layers of overpaint from a restoration done in the ’90s that was later found not to be true to the artist’s palette. The yellow and red areas, in particular, were too dark.

A few weeks ago, Julie Wolfe, associate conservator of decorative Arts and sculpture at the J. Paul Getty Museum, told me that making a choice about what paint system to use for the restoration of Three Brushstrokes took years of consideration.

Not much was widely known about Lichtenstein’s paint system before the Getty started looking into his studio techniques five years ago.

In the early years of sculpture making, Lichtenstein modified industrial paint systems in order to fine-tune the colors. He wasn’t satisfied with the colors available from the industrial products alone, so the surfaces of his sculptures were finished with a brushed-on glaze of color made from mixing clear industrial resin with artists’ acrylic paints.

Later on, Lichtenstein switched to a different system that exclusively used industrial products—sprayed on and smooth—which seemed to last longer when exposed to the outdoors. During his career, Lichtenstein even consulted with owners of his sculpture requiring restorations and advised they repaint even his early works using the later painting technique. As a result, there are now very few sculptures left that retain the artist’s original approach. No one is sure exactly how many, but based on extensive research, the best estimate is less than a handful.

Which approach would be best for conserving Three Brushstrokes? Should it be hand-painted, or conserved using the later sprayed-on paint approach, which might last longer? And how could conservators match the original hidden colors on the piece?

In seeking answers to these questions, Wolfe has been working with the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation in New York, and the Roy Lichtenstein Estate and studio. The Estate’s studio manager, James DePasquale—who, it turns out, worked closely with Lichtenstein and originally painted all of his outdoor sculptures—has been an invaluable resource. Wolfe also turned to another important partner, the Getty Conservation Institute, to do paint analysis and forensic work. The Conservation Institute is already undertaking related research as part of its own Outdoor Painted Surfaces initiative, and often does conservation research and analysis in partnership with the Getty Museum. The GCI’s Lichtenstein case study can be viewed here.

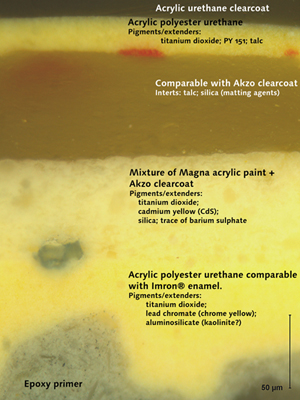

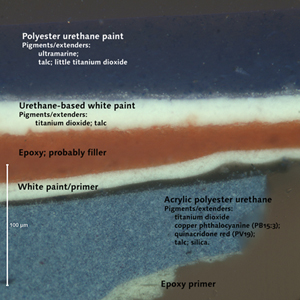

It was paint analysis by Conservation Institute scientists Alan Phenix and Rachel Rivenc in 2005 (accomplished by taking tiny samples from different areas of the sculpture) that determined the original paint was still underneath the current restoration paint. The beautiful cross sections viewed under a powerful microscope backed up the oral history gathered from DePasquale—down to the discovery that during the restoration, red paint had been sprayed on before the last coat of yellow, leaving tiny dots of red paint visible in the underlayer of yellow. Phenix and Rivenc used comprehensive analytical methods (microscopical examination and chemical analysis) to obtain essential information that helps to document the history of the piece, and, importantly, to give insight into the original methods Lichtenstein used with his outdoor painted sculpture.

Cross section of Three Brushstrokes' yellow paint

Cross section of Three Brushstrokes' blue paint

“This conservation effort has been incredible for us,” says Tom Learner, the scientist who leads the Modern and Contemporary Art Research Department at the Conservation Institute. “This project has helped to guide our ongoing endeavor to discuss, compare, and document the protocols for repainting adopted by other estates and foundations of sculptors creating outdoor painted work, information that is invaluable to conservators and artists everywhere.”

Removing a rare original paint layer is a difficult decision to make, but is an inevitability with most outdoor painted sculpture. Leaving an aged coating on metal can cause more damage to the structure in the long term. So the collective decision, based on extensive research and much discussion, was to remove the paint on Three Brushstrokes down to the metal, and then to faithfully recreate the artist’s original intent with the help of DePasquale.

Using thorough documentation, the Getty’s goal was to have the treatment of Three Brushstrokes serve as invaluable archival documentation of his early sculptural painting technique.

Though one would never repaint a painting or even an indoor sculpture, it is widely accepted to repaint outdoor works.

Over the course of several visits to the Getty Center, DePasquale repainted the sculpture exactly as he had in 1984, with only minor tweaks where original products had been discontinued. He also provided true color samples from the artist’s studio that have now been carefully archived, and the paint process Lichtenstein used has been recorded in detailed steps for future treatments.

Check out the amazing time-lapse of the repainting of the sculpture at the top of this post. Images were taken every 20 seconds with a digital camera set up in the Getty Museum’s spraybooth.

Having a living resource to turn to during the conservation of this work has been incredibly helpful as well as highly unusual, and a major influence in choosing a conservation approach. Oftentimes, conservators are left to grapple with these tough dilemmas on their own—another reason the GCI wants to see a more systematic approach to conserving these works adopted.

For me, it has been eye opening to see the monumental effort, and passion, it takes to conserve outdoor painted sculptures. I’ll never look at them quite the same way again.

To date, the Getty is the only institution to have restored a Lichtenstein sculpture using the early paint system.

Lichtenstein’s Three Brushstrokes will go back on display at the Getty Center in the near future, and we’ll update you here when it does.

So did Mr. De Pasquale follow the paint application found in the chemcial/mircoscopic analysis”red paint had been sprayed on before the last coat of yellow, leaving tiny dots of red paint visible in the underlayer of yellow.”?

So… no mention made of a coversion coating for the raw aluminum. Paint will not stick to aluminum without it.