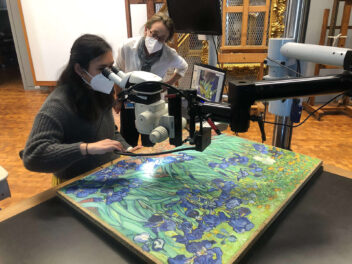

Julie Wolfe applying coatings to Running Man, 1978, Dame Elisabeth Frink. Bronze, 75 x 51 x 25 ¾ in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Gift of Fran and Ray Stark, 2005.106.2. Sculpture © Estate of Elisabeth Frink

Julie Wolfe, a conservator at the Getty Museum, is wrapping up several years of research on coatings used to preserve the outdoor sculptures in the Fran and Ray Stark Collection.

Coatings used for outdoor bronzes at the Getty fall into two categories, wax and acrylic, and Julie has been reviewing the history of these different types and testing them on swatches. Much of her attention has been focused on the proprietary acrylic coating Incralac, which was developed in the 1960s specifically for copper alloys. Incralac was designed for industrial use and has been widely adopted for art conservation—but because it is toxic and may be difficult to remove, conservators disagree about the advisability of its use.

Because of this lack of consensus in the field, Julie has been systematically exploring the pros and cons of Incralac, learning the development of the original formulation, and reviewing published performance testing on the product. Simultaneously, she has been creating a substitute that can be made in-house without the high level of toxic solvents. An Incralac alternative is increasingly in demand due both to environmental concerns and constantly changing regulations.

This issue began to concern Julie in 2005, when she was charged with creating a maintenance plan for over two dozen outdoor sculptures that the Getty Museum had acquired. The bronzes all had Incralac coatings that were twenty years old—even though the coating should be replaced every ten years. Since then, she has been working tirelessly to remove the aging acrylic coating on each sculpture and using this as an opportunity to study the Incralac coating and alternatives.

Through her work Julie is hoping to fill a gap in practical research on coatings for outdoor sculptures and monuments. Much of the existing research, she notes, focuses on industrial use, and each artwork presents its own unique set of materials, surfaces, and challenges. For example, Incralac may have a different performance on a polished copper architectural element compared to a patinated bronze surface applied by the artist’s foundry or perhaps a weathered surface from outdoor exposure.

With the collaboration of Getty Conservation Institute scientists, Julie’s findings on the history of Incralac will be published in a paper this fall with the Journal of the American Institute for Conservation. At the International Council of Museums–Committee for Conservation (ICOM-CC) conference in Copenhagen this September, she shared her research on the development of an in-house non-toxic Incralac alternative—available through the Journal of the American Institute for Conservation.

For more on Julie’s work with the conservation of outdoor sculpture, read about recent conservation efforts on a Barbara Hepworth bronze. For a deeper dive, Julie points to materials produced by the National Park Service on preserving outdoor sculpture and monuments. If you work on the conservation of outdoor sculpture and monuments, she would love to be in contact.

See all posts in this series »

Exelente

50 years ago, in elementary school, I was taught King Tut history.

Since then, topics about the king has always perked my attention.

Please, if you have an email list of people you update, put my name on it.

Thank you and good wishes moving forward

Important work, but “…should be replaced after ten years…” is an unsustantiated albeit common belief.

Be that as it may, there are indeed good alternatives to Incralac, for clearcoating outdoor bronzes. See Mira, et al in proceedings of Eurocorr 2017, for several abstracts and papers sharing extensive research results from a three year EU funded joint project.

And Lins, et al, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art several years ago completed a multi year (IMLS-funded?) study evaluating several very different available protective clearcoatings, including Incralac, and including nonacrylics among them Permalac, a very longlasting yet easily removeable product which is being very widely adopted.

The more good research in this area, the better!