I just attended the 2015 meeting of the Museum Computer Network—my first time attending a conference specific to the museum world. This event was filled with interesting people and discussions, and it was a real pleasure to participate.

The discussions around digital publishing in particular have left me with a sense that our community of museum technologists has its work cut out for it. As an example, here are some of the challenges that came up in the panel discussion on digital publishing on the conference’s last day:

- Kris Thayer (Mia) talked about building twelve issues of an award-winning digital magazine using the Adobe DPS tools. However, due to problems of vendor lock-in and the proprietary nature of the platform, her team is not continuing their work in this format. When their Adobe DPS license expires, two years of work will disappear from the Apple Newsstand, as if they had never existed.

- Ahree Lee and Susan Edwards discussed their work on the Mellini publication at the Getty. They spent a lot of time coming up with a unique UX for an unconventional publication, but some of the scholars on the project balked at the idea of editing their content in the Drupal interface that powered the backend. To the sound of groans, they described the painstaking process of exporting the content of a massive, born-digital project into MS Word for editing, only to be re-imported upon completion.

- Lauren Makholm (AIC) spoke about the digital publishing program at the Art Institute of Chicago, where they have successfully launched a series of online art catalogues using the open-source OSCI Toolkit. But even at an institution where buy-in exists at the highest levels, there was plainly some anxiety about how a small team would be able to keep an expanding number of complex web-app publications running for the indefinite future.

No Silver Bullet (Yet)

Digital publishing is still in its infancy–especially in museums and universities. I don’t think anyone has the silver bullet yet. I do think that the stories above represent a set of common problems which plague the industry as a whole: the problems of proprietary software and vendor lock-in, of providing tools that non-developers are comfortable with, and of ensuring the long-term accessibility of the work we produce.

In order to solve the problems our industry faces, we first need to craft better tools.

Specifically, we need a set of tools for digital publishing that can do the following:

- Avoid vendor lock-in. We are living in the midst of an arms race by hardware and platform manufacturers that are competing for dominance. As amazing as the latest innovations by Apple, Google, Adobe, Facebook, et. al. are, I think that we need to resist the temptation of the shiny and new if it comes at the expense of openness and accessibility. This applies both to hardware (like Apple’s iBooks or NewsStand apps) and software (ex., Facebook’s Instant Articles).

- Simplify the experience for authors and editors. There are many great open-source tools for editing text, images, etc. But the interfaces for these tools are often confusing for non-developers. Proprietary applications like MS Word or Google Docs remain dominant for a reason—non-technical users prefer them.

- Plan for the long term. The technology field is constantly advancing. But in the academic or cultural worlds we have to think with a longer time horizon in mind. The ethos of “move fast and break things” isn’t going to fly. What will become of our projects five years from now? Ten? Twenty? This is a problem that we don’t share with most of the wider tech industry, but it is hugely important. We’ve been entrusted with the preservation of human knowledge and culture, and we need to choose our tools with that responsibility in mind.

Next Steps

I believe that the combination of plain-text document formats and static site generators is a powerful tool for digital publishing that could solve many of these problems; this was the subject of my own talk at MCN 2015. The issue of usability (see #2 above) is where the most work remains to be done.

A concrete example: What if we provided authors and editors with a beautiful, distraction-free writing environment instead of the cramped WYSIWYG window included in the typical CMS? What if that editing interface could display the results of git diff in place as you typed, a tracked-changes view with all the power of Git under the hood?

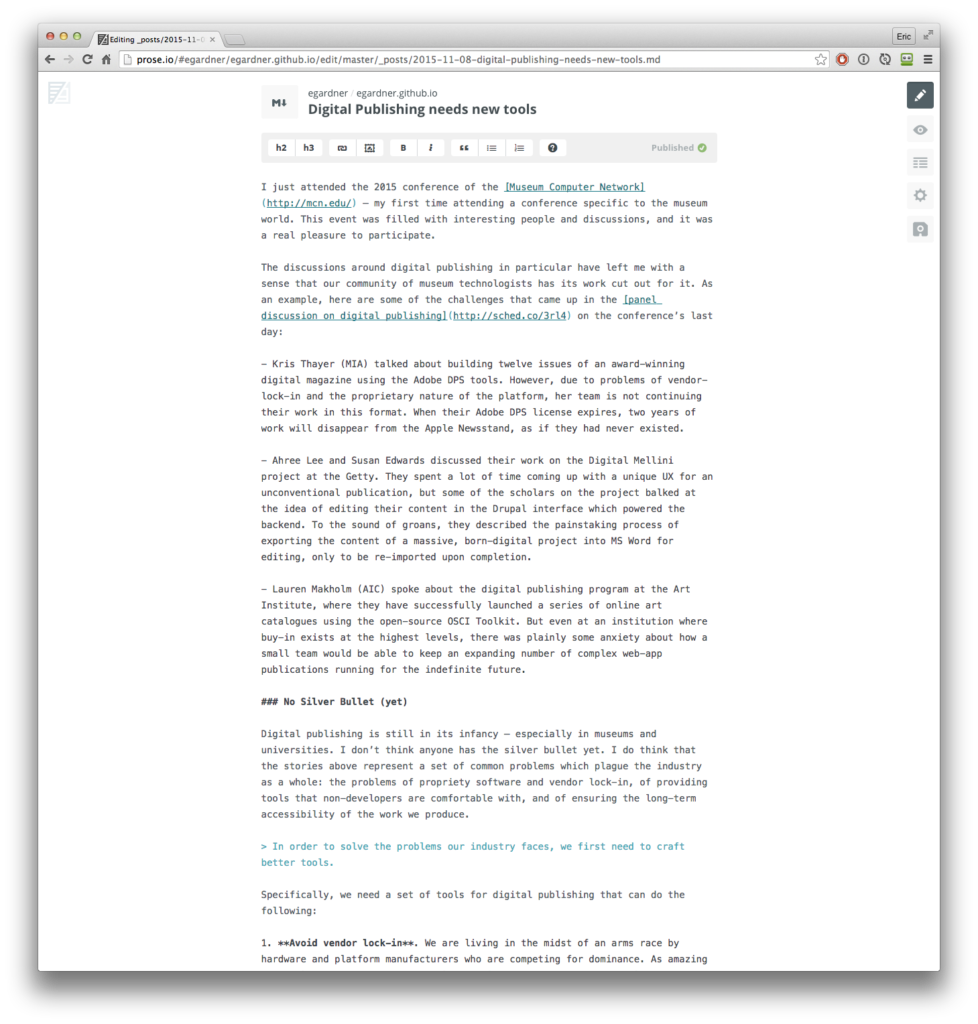

The prose.io project is a great example of this kind of technology. Prose is a web application that provides a simple and elegant interface for working with Markdown files hosted on the code-sharing website Github. With the addition of a few features (better support for footnotes/citation, track changes, etc.) this could be a great tool for creating born-digital publications, one that our scholar and editor colleagues might actually want to use.

Above: the text of this post viewed in prose.io’s online Markdown editor.

The field of digital publishing presents us with many different challenges. Right now I think we can have the most impact by lowering the barrier to entry that stands between us and many of our colleagues. Can you think of other ways to “humanize” the experience of writing, editing, and publishing with open-source tools?

Great post, Eric! As an editor, I esp appreciate your sensitivity to editorial concerns. Like you said, there’s a reason why Word is so prevalent. But editors/writers need to be open to new ways of doing things too. It makes sense that editors and tech people collaborate on developing new tools that are specially intended for this new medium.

Thanks, Nola! I think that the best way forward is for editors and tech folks to “meet in the middle.” Developers can benefit from learning more about the content they are responsible for just as much as writers and editors can benefit from learning a little more about code.

I’m with you, Eric. And although Track Changes is serviceable and familiar, it’s not perfect. We can aspire to create something for editing digital pubs that works even better.

It’s so interesting to see all the back-end and back-everything that goes into making something digital more human/humane. The formula of human + computer = stuff for humans, and dialogue between tech and user, seems like an ongoing issue in itself, and even more so for new realms such as digital publishing. Even once you narrow down all 1001+ the tools out there that may be appropriate for a particular project, how do you choose which tool to eventually use? Is it always an experiment?

It’s a shame that Drupal doesn’t offer something akin to WordPress’s “distraction-free editing mode”, which expands the editor to make it nearly as big as the browser window. I think something like this might make native editing in Drupal more attractive to users.