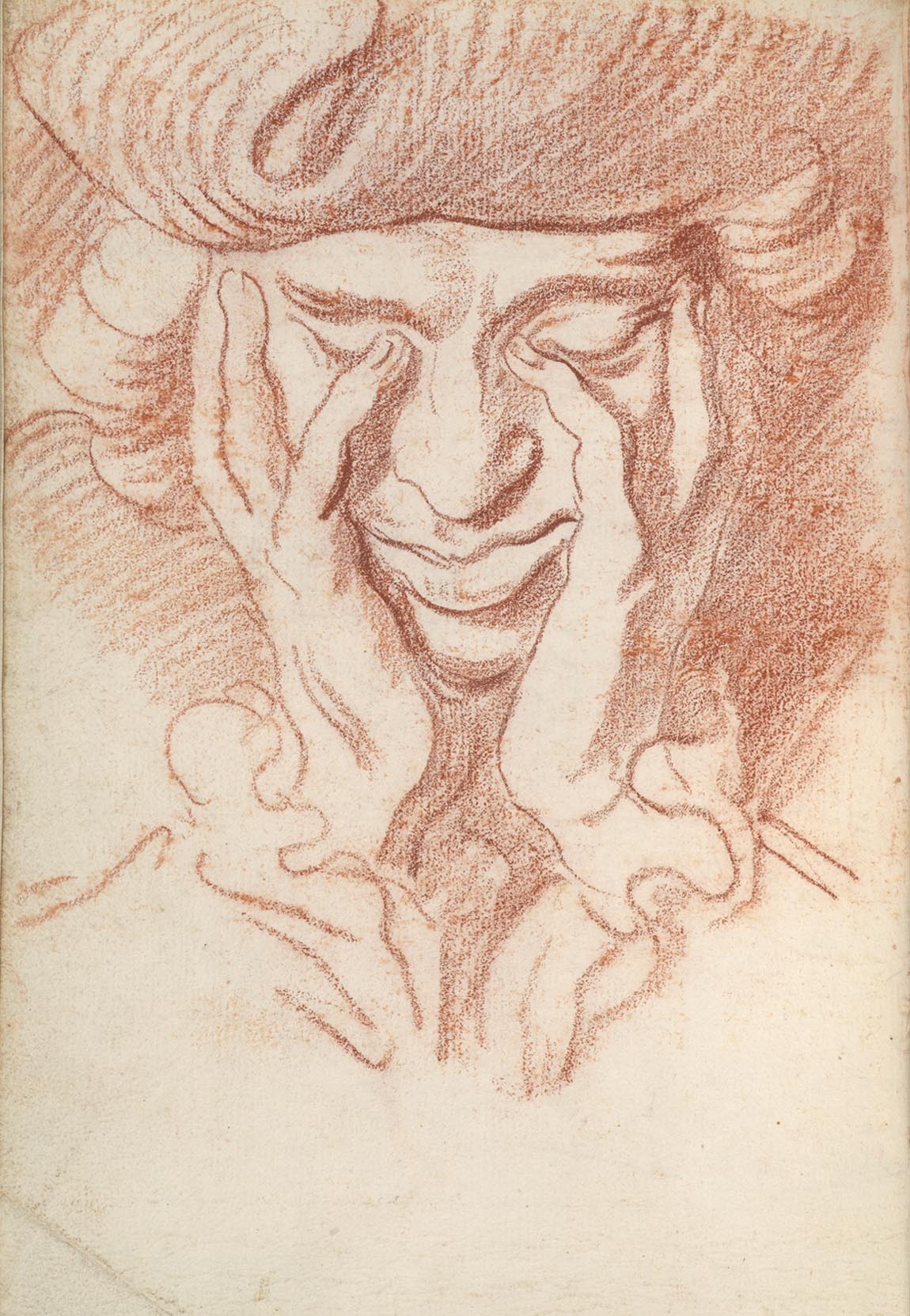

Self-Portrait, about 1730, Edme Bouchardon (French, 1698–1762). Red chalk, 19.8 x 13.5 cm. The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased in 1907. Photography by Graham S. Haber

Many visitors to the exhibition Bouchardon: Royal Artist of the Enlightenment will be intrigued by one particular red-chalk drawing. You might have already discovered it on street banners lining the streets of Los Angeles, on the Getty’s website, or on signage while visiting the Getty Center.

Design for Bouchardon exhibition street banners, now mounted on light poles throughout Los Angeles

The drawing is an unusual portrait of a young man; his eyes are closed, his head tilts downward, and he holds his face in both hands—all from a close-up, frontal viewpoint. This portrait is actually of the artist, Edme Bouchardon, with his distinctive aquiline nose and thick-lipped mouth.

Without visiting the show or seeing the drawing in person, it’s difficult to see that it is quite small: less than 8 inches high. There’s a simple reason for its diminutive size: Bouchardon drew the self-portrait on a page in his Vade Mecum. Vade Mecum—Latin for “come with me”—is the title of two of Bouchardon’s luckily preserved notebooks. The French artist carried these small, lightweight notebooks in his pocket while he walked around Rome, where he lived from 1723 to 1732 during the early stages of his career.

In the exhibition, one of the Vade Mecum books is open to the page featuring this exceptional self-portrait. Bouchardon emphatically retraced the profile of his right palm along with the curves of his lips, eyebrows, and hat, while delineating his shirtsleeves lightly with a single serpentine line. Is this a representation of the artist’s loneliness or a moment of inspiration? We will never know for sure, but all of us, caught by the strength of this image, are free to create our own interpretations.

The self-portrait is somewhat of an anomaly in the notebooks, as most of the sketches are of artworks Bouchardon encountered during his time in Rome. He remembered ones he particularly liked by making quick sketches of them.

Saint Dominic, 1723-32, Edme Bouchardon. Red chalk, 18.2 x 12.5 cm. The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased in 1907.Photography by Graham S. Haber

The second notebook on display showcases an image that is more representative of the drawings in the two volumes. It’s a lively copy of a statue of Saint Dominic in Saint Peter’s Basilica, carved by the French sculptor Pierre Legros, who the young Bouchardon admired for his prolific oeuvre and prestigious career in Rome.

Saint Dominic, 1706, Pierre Legros (French, 1666–1719). Marble, about 4 meters high. Rome, St. Peter’s. Image courtesy Corriere della sera

Legros’s Saint Dominic was the first of the monumental marble statues representing the founders of religious orders—in this case, the Dominicans—carved for Saint Peter’s nave.

With quick, firm lines, Bouchardon marked the contours and the draperies, while rendering the hands and face with small strokes. Although rapidly sketched, the dog that holds a lighted torch to illuminate the world—a vision experienced by Dominic’s mother during her pregnancy—has all the vitality of the original. It looks ready to jump out of the niche!

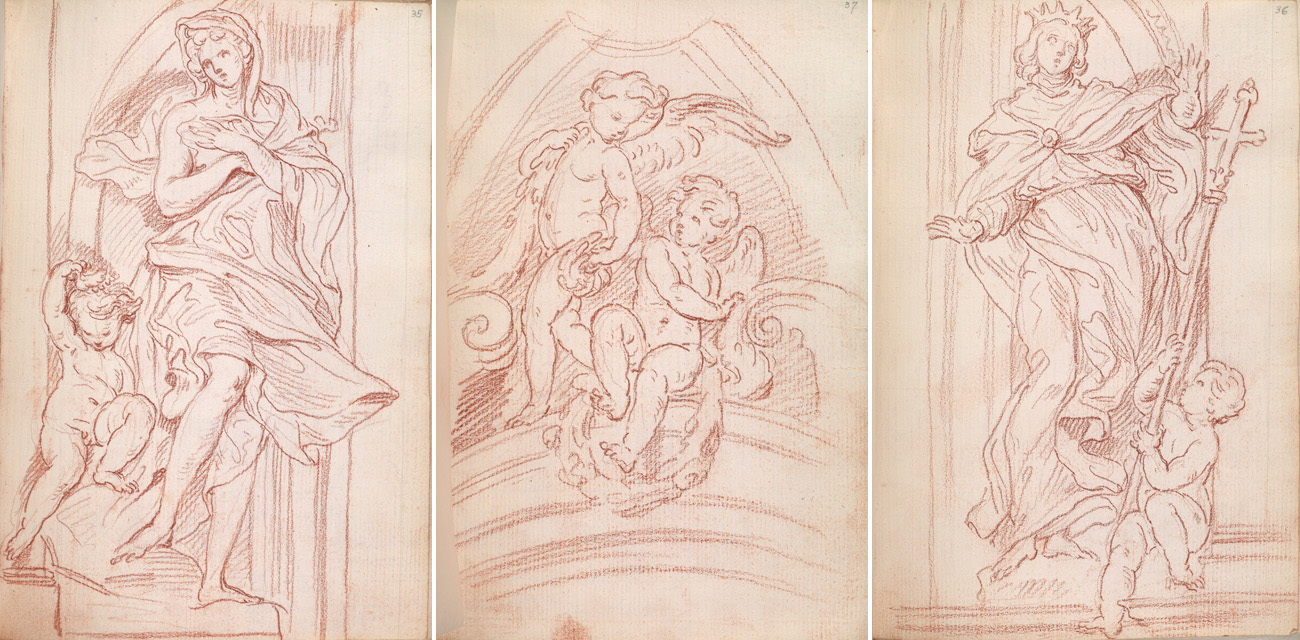

Sometimes Bouchardon diligently copied all the elements of a sculptural ensemble. He filled twenty-one pages of one notebook with copies of all the stucco figures representing the Virtues and putti that decorate the windows under the vault of Rome’s Church of the Gesù (below), moving from left to right in the nave.

Nave of the Church of the Gesù, Rome. Photo: Anne-Lise Desmas

Detail of the nave of the Church of the Gesù, Rome, showing sculpted putti and allegorical virtues around the windows. Photo: Anne-Lise Desmas

Statues of Virtues and Puttos, 1723–32, Edme Bouchardon. Red chalk, each 18.2 x 12.5 cm. The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased in 1907. Photography by Graham S. Haber

On another occasion, impressed by the design of a fountain erected in the middle of a square, he stopped his walk to sketch a memory of it on his notebook. Who wouldn’t be charmed by the Turtle Fountain gracing the small Piazza Mattei?

Turtle fountain outside the Piazza Mattei, Rome. Photo: Carlomorino. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Turtle Fountain, 1723–32, Edme Bouchardon. Pen and ink, 18.2 x 12.5 cm. The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased in 1907. Photography by Graham S. Haber

During his walks through the city, the young artist clearly had his eyes wide open, constantly looking around and even catching statues erected high on top of many Roman churches, including a statue of a winged Fame decorating the façade of Sant’Andrea della Valle.

Façade of Sant’Andrea della Valle church, Rome, 1655–63, Carlo Rainaldi (Italian, 1611–1691). The winged statue of Fame (about 1666) by Ercole Ferrata is silhouetted against the sky at left. Photo: Martin Falbisoner, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fame, 1723–32, Edme Bouchardon. Red chalk, 18.2 x 12.5 cm. The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased in 1907. Photography by Graham S. Haber

Even more fascinating, Bouchardon’s quick, lively notebook sketches may have been executed while he was on his way to or from long, intense drawing sessions in which he meticulously copied other artworks in highly detailed, large-scale formats. For instance, he executed one of the largest red-chalk drawings on view in the show (29 inches high), a copy of a Saint Matthew fresco on the pendentives of Sant’Andrea della Valle, the same church where he drew the Fame.

Pendentive with Saint Matthew the Evangelist, 1622–27, Domenichino (Italian, 1581–1641). Fresco. Rome, Sant’Andrea della Valle. Photo: Anne-Lise Desmas

Saint Matthew, 1724–25, Edme Bouchardon after Domenichino’s fresco in Sant’Andrea della Valle, Rome. Red chalk. Paris, Musée du Louvre, Département des Arts graphiques. Image © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée du Louvre) / Michel Urtado

Young artists like Bouchardon who had been granted a sojourn at the French Academy were encouraged to study after Domenichino, a leading painter in Italy in the early seventeenth century. The academy’s director obtained permission to have scaffolding installed in the church to give students access to Domenichino’s frescoes painted on the dome’s pendentives, the curved triangular segments of a vault.

Bouchardon drew Domenichino’s four Evangelists. He produced the one on view at the Getty Center, Saint Matthew, by pasting together a main sheet and three inserted pieces, forming a T-shaped motif to mimic the format of the pendentive. Typical of his early years in Rome, Bouchardon used fine, dense, heavy, and deliberately crosshatched lines to fill in the composition.

The central sheet is more oxidized than the others and has traces of thumbtack holes. In all likelihood, it hung in Bouchardon’s studio, while the other sheets were glued together after the collection came to the Louvre. According to his contemporaries, Bouchardon hung many of the drawings he realized during his stay in Rome on the walls of his lodgings in Paris.

These artworks currently hang on the walls of the Exhibitions Pavilion at the Getty Center, so visitors can discover Bouchardon’s incredible studies made after masterpieces of antique statues, paintings by Raphael, sculptures by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, and more.

In contrast to large-scale pieces like Saint Matthew, Bouchardon’s two notebooks provide a more intimate window into the artist’s experience of Rome. Whether copies of statues or a captivating self-portrait, the sketches reflect Bouchardon’s inner life and his many sparks of creative inspiration.

Comments on this post are now closed.