José Olaya, 1828, José Gil de Castro. Oil on canvas, 204 x 137 cm. Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Antropología e Historia del Peru, Lima. Gil de Castro Project. Photo: Daniel Giannoni

In 2008 a team of Latin American scholars led by Natalia Majluf, director of the Museo de Arte de Lima (MALI) in Peru, was awarded a Collaborative Research Grant from the Getty Foundation for a study of painter José Gil de Castro (1785–1841). MALI is now releasing a new publication presenting their research, Más allá de la imagen (Beyond the Image). In celebration of the team’s accomplishments, I spoke with Dr. Majluf about completing the publication on this beloved painter and what she and her fellow scholars learned along the way.

Let’s begin by telling readers a bit about the topic of MALI’s new publication, and how this project came to be.

Cover of the new book Más allá de la imagen

The book presents the first results of a long-term collaborative effort to study the work of José Gil de Castro, a painter who almost single-handedly created the enduring images of Latin America’s heroes of independence, from Simón Bolívar and José de San Martín, to Bernardo O’Higgins and José Bernardo de Tagle. Our research team had envisioned this project for a long time, but the Getty Foundation collaborative research grant is what made this undertaking possible. There are very few institutions in the region that promote research across national borders and fewer still that support technical studies. Más allá de la imagencenters precisely on the material research undertaken by the team.

One of the qualities of Gil de Castro I find most interesting is, in fact, “beyond the image” and has to do with the internationalism of his own creative endeavor: born in Peru, working for a time in Chile, and making portraits of Argentinian military leaders. Incidentally this internationalism also has a nice parallelism with your project team.

Yes, the international makeup of the team has been central, as Gil de Castro’s paintings are dispersed throughout the region, mainly in Argentina, Chile, and Peru. We had the good fortune of being able to secure the support of the Instituto de Investigaciones sobre Patrimonio Cultural, Universidad Nacional de San Martín in Buenos Aires, and the Centro Nacional de Conservación y Restauración in Santiago. Their participation was crucial to completing the technical studies.

Gil de Castro project team members (left to right) Carolina Ossa, Natalia Majluf, and Federico Eisner examining one of the artist’s paintings. Photo: Museo de Arte de Lima

It’s important to bear in mind that the artist was living in Santiago when General San Martín’s army arrived in Chile; his officers came mostly from Buenos Aires, where there were virtually no significant painters. Thus, most of them commissioned portraits from Gil de Castro, which they brought back upon their return or sent to their families. This explains why most portraits of the Argentinean heroes of independence show evidence of being rolled up for travel, as we discovered through x-rays of the paintings.

Did works preserved in Caracas, Lima, or Santiago suffer the same fate?

In our book, Néstor Barrio and Laura Malosetti propose a “material critical fortune” of Gil de Castro’s works. Indeed, the paintings are better preserved in countries like Chile, where Gil de Castro is considered a founding figure of national painting, as opposed to Buenos Aires, where he is mostly unknown to general audiences. And though he is important in Peru, Gil de Castro was not always recognized, which explains why many of his paintings located there also suffered from decades of neglect.

Ferdinand VII, 1815, José Gil de Castro. Oil on canvas, 122.5 x 97 cm. Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Antropología e Historia del Peru, Lima. Photo: Daniel Giannoni

This scholarly endeavor is an art historical one, but at the same time you’ve worked with a team of scientists and conservators to better understand Gil de Castro’s work.

To my knowledge this is the most extensive series of technical analyses to have been undertaken for a single painter in Latin America. We were able to examine in great detail over 40 paintings and do partial analysis of around 20 other works. We also studied the work of many of his contemporaries in Chile and Peru. What we have done for this publication is bring together an art historian and a conservator to work on each of the chapters, to ensure that the collaborative spirit of the project was also carried on in the book.

What is one of the more interesting technical discoveries that you made in your research?

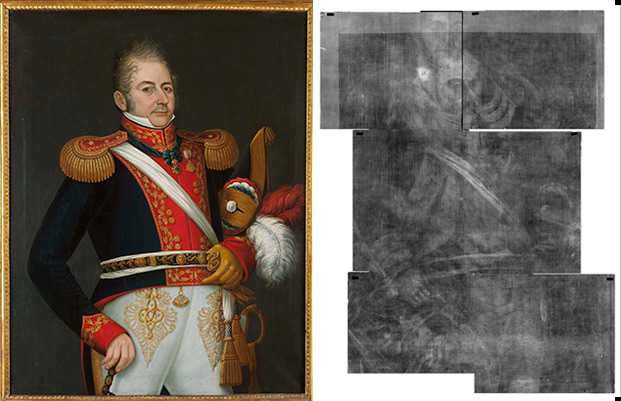

That the portrait of a high-ranking officer of the Chilean army had been painted over an earlier portrait by Gil de Castro of the king of Spain.

Left: Francisco Calderón Zumelzú, 1822–23, José Gil de Castro. Oil on canvas, 114.7 x 89.5 cm. Museo Histórico Nacional, Santiago de Chile. Gil de Castro Project. Photo: Jorge Sacaan. Right: Detail of x-ray image made in April 2009 of José Gil de Castro’s portrait of Francisco Calderón Zumelzú, 1822–23, showing a copy of the earlier portrait of Ferdinand VII that the artist painted over. Museo Histórico Nacional, Santiago de Chile. Gil de Castro Project

What a powerful, and symbolic, act of erasure.

Indeed, and further x-rays of contemporary paintings revealed that such recycling of older canvases was common practice: we also found a portrait of the Peruvian Viceroy José de Abascal under a painting of General San Martín by Mariano Carrillo, a contemporary of Gil de Castro. On another note, the studies made of works by contemporary artists in Chile and Peru has allowed us to identify technical traditions peculiar to Lima, where Gil de Castro was trained.

Text of this post © J. Paul Getty Trust. All rights reserved.

The research team’s work brings new understanding to an important transitional period, laying the foundation for future scholarship. At the present they continue to work together on a catalogue raisonné for Gil de Castro, which will be published in 2014 in tandem with an international traveling exhibition in Buenos Aires, Lima, and Santiago. For more information about “Más allá de la imagen” contact MALI.

Comments on this post are now closed.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks