ひろしま/hiroshima #9 (Ogawa Ritsu), 2007, Ishiuchi Miyako. Chromogenic print. © Ishiuchi Miyako

Beginning October 6, the work of Japanese photographer Ishiuchi Miyako will be the subject of a major exhibition at the Getty Center, the first museum show in the United States to highlight the career of this groundbreaking artist. But today—exactly two months prior to the opening of Ishiuchi Miyako: Postwar Shadows—marks the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, a topic that has engaged Ishiuchi since 2007.

For the last eight years, Ishiuchi has traveled to Hiroshima to photograph objects affected by the atomic bombing of that city, now preserved by and housed in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

View of Peace Memorial Museum from Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park

Shimomura Mari, a curator at the museum who has assisted many artists intent on utilizing artifacts from the collection for their own creative projects, acknowledges that Ishiuchi approaches the subject unlike anyone else. When I visited the Peace Memorial Museum last year, Shimomura told me that Ishiuchi’s straightforward, intuitive approach surprised her initially. Ishiuchi’s equipment and setup are very basic (she occasionally uses an automatic point-and-shoot camera) and she often speaks to the objects while photographing them. Both casual and intimate, Ishiuchi’s practice involves fostering a kinship with each object that she ultimately decides to depict. Moreover, Ishiuchi tends to isolate fragments of clothes or details in the garments—such as hems, buttons, lace, wrinkled fabric—as her subjects. She presents them in vivid color and in large scale, thus encouraging viewers to look at what might otherwise escape notice, particularly when displayed in Plexiglas vitrines.

Ishiuchi using her point-and-shoot camera, surrounded by cameramen

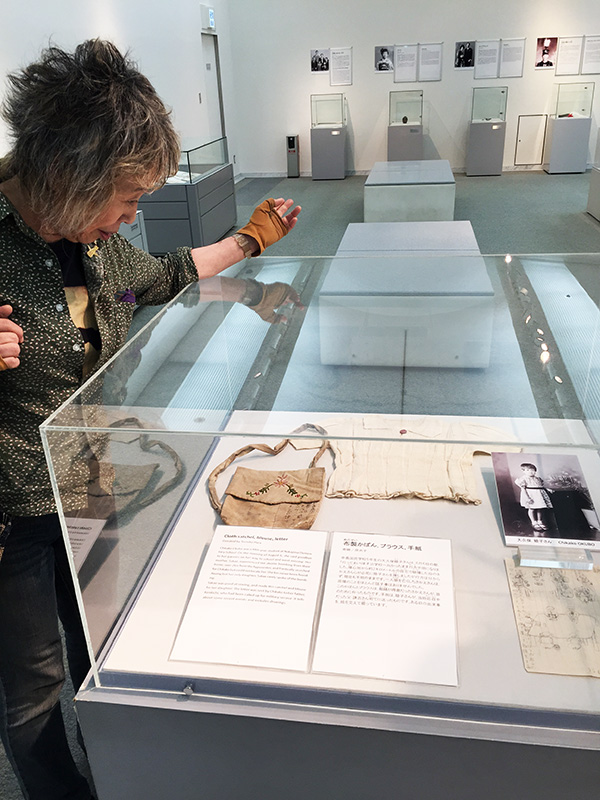

Ishiuchi in the Peace Memorial Museum, looking at a satchel that she photographed last year that is now on display

Another distinguishing aspect of Ishiuchi’s project involves the garments and objects she selects: many were formerly owned by women. Ishiuchi underscores this point in the title of the series, ひろしま/hiroshima, which contains Japanese Hiragana characters and Rōmaji (Roman letters) characters, both spelling the word hiroshima.

She includes Hiragana, a form of writing historically used by women in Japan, to indicate that this project was made from the perspective of a woman. Mindful of Ishiuchi’s concern with the personal, feminine qualities of both her work and the subjects she chooses, Shimomura often pre-selects clothing worn by women at the time of the bombing. After eight years of working together, Shimomura understands what Ishiuchi might like to photograph now, sometimes identifying objects as soon as they are donated.

ひろしま/hiroshima #43 (Yamane Shizuko), 2007, Ishiuchi Miyako. Chromogenic print. © Ishiuchi Miyako

I had the opportunity to visit Hiroshima again last month, this time to observe Ishiuchi as she photographed several objects donated to the Peace Memorial Museum collection within the past year. Surrounded by journalists, three cameramen, museum staff, and other onlookers such as myself, Ishiuchi and Shimomura methodically arranged each object on tracing paper placed on the floor of the museum’s offices.

Ishiuchi initially photographed objects while backlit from a light box, but now she typically relies on natural, available light when photographing the objects. However, on this overcast day she also utilized a lamp to illuminate the room. She studied the clothes intently, squatting and kneeling beside them to inspect the tears and holes caused by irradiation, as well as the intricate, handmade qualities visible in the stitching, patchwork, and mending. After hovering over the objects, and photographing them while standing up, she leaned in to look closely at the fabrics, the stains, and the time worn by each object.

Ishiuchi photographs a detail of the jacket

On this visit to Hiroshima, Ishiuchi gave a talk at Hiroshima MOCA, where some of her work is currently on view in the exhibition Life=Work. After Ishiuchi spoke about the importance of viewing Hiroshima in the present day, as a current subject rather than a historic one, a hibakusha (survivor of the blast)—who recently donated a blouse owned by her sister to the Peace Memorial Museum—identified herself and began to weep. That blouse, discolored over time and stained pink by the blood from the victim who wore it on August 6, 1945, now appears in a photograph by Ishiuchi on display at Hiroshima MOCA. The woman thanked Ishiuchi.

ひろしま/hiroshima #99 (Hagimoto Tomiko), 2014, Ishiuchi Miyako. Chromogenic print. © Ishiuchi Miyako

But Ishiuchi resists yoking together her photographs with the histories of the objects and the stories about the people who donated them, information that resides on the Peace Database. She prefers to present these articles from the Peace Memorial Museum collection as contemporary forms. In fact, she routinely hangs the photographs at various elevations on the walls of galleries and museums, giving the impression that the objects “float” like ghosts, or rather like animated objects imbued with life.

Ishiuchi in front of her work at Hiroshima MOCA

In two months, when approximately twenty works from the series ひろしま/hiroshima go on view at the Getty, the photographs will take on a new life in a new city, in the context of Ishiuchi’s exhibition. As the show approaches, people often ask how the work will be received here, to which I feel obligated to respond, “I don’t know yet.” Ishiuchi describes the presentation of ひろしま/hiroshima at an American museum as the ultimate achievement, commenting that it causes her to believe “there’s hope for this world after all.”

Hey Great post amanda- now I am looking forward to the show even more! I hope you get lots of mileage with this blog entry: it’s sweet and very alluring. I love her and can’t wait to see the photos. Thanks for being such a champion of Ishiuchi and her story! xox margie