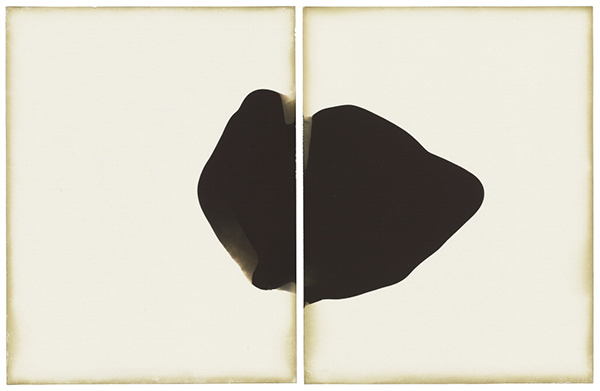

Spin (C-824), 2008, Marco Breuer. Chromogenic paper, embossed and scratched, 13 5/8 x 10 5/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Purchased with funds provided by the Photographs Council, 2014.9.7. © Marco Breuer

Photography is a means of representing the world. But that’s not all it can be, as a new exhibition at the Getty Museum aims to show.

“Documenting the world is only one way of using photography,” said Virginia Heckert, head of the Museum’s Department of Photographs and curator of Light, Paper, Process: Reinventing Photography. “Other photographers go into the darkroom and experiment. They push the medium to its limits, taking advantage of what others might see as mistakes.”

The seven artists represented in Light, Paper, Process make experiment and chance visible in their work, combining these with the traditional materials of photography: light-sensitive emulsions, paper, chemical development. “These are artists who embrace challenges not as limitations,” Virginia explained, “but as opportunities to work in the same experimental spirit that led to the invention of the medium.”

Exposing Photographic History

Haloid Platina, exact expiration date unknown, about 1915, processed 2010, 2010, Alison Rossiter. Gelatin silver print, 5 x 7 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Purchased with funds provided by the Photographs Council, 2013.77. © Alison Rossiter

Several artists in Light, Paper, Process connect to the history of photography in a tangible way, employing vintage photographic papers, negatives, and lenses in their work.

Alison Rossiter sources expired photographic papers dating back to World War I to create “found photograms.” Her small, shimmering studies evoke moody landscapes, Abstract Expressionist paintings, and the earliest photographic experiments from the 1830s and ‘40s. Some of the tones, patterns, colors, and textures on these petite rectangles derive from her darkroom experiments pouring and pooling developer; others reflect the history of the vintage paper itself, which has been exposed to light leaks over decades in its original packaging.

Lisa Oppenheim employed a single 19th-century negative to create a groups of darkly golden sun prints. By exposing each print to sunlight at different times of day and for varying lengths of time, she created luminous compositions that suggest 19th-century alchemical experiments and the changing moods of the sky.

Heliograms July 8, 1876 / October 16, 2011, 2011, Lisa Oppenheim. Gelatin silver print exposed with sunlight, toned, 11 13/16 x 11 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2014.44.3. © Lisa Oppenheim

Against Perfection

All seven of the artists in the show work with repetition, seeking to uncover how a similar technique or gesture can lead to unexpected results.

For his sinuous Water series, James Welling plunged sheets of photographic paper into a basin, achieving through this simple act a remarkable variety of shapes, tones, and colors. “It’s the same gesture again and again, with each result different,” explained Virginia. “It’s not about achieving the perfect image one time only, but about mastering the gesture and seeing its diverse realizations.”

Water, 2009, James Welling. Chromogenic print, 23 3/4 x 19 3/4 in. Courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles. © James Welling

Marco Breuer uses heat, friction, and abrasion instead of light, employing tools such as smoldering coal, lit fuses, steel wool, knives, drills, razor blades, even a loaded gun. In one experiment, for example, Breuer laid a sheet of muslin on a sheet of photographic paper in the darkroom and lifted a match to it. The light from the match created a photogram of the weave of the cloth, while the heat started to burn the paper. The resulting work, Untitled (100% Cotton), is both a photogram and a recording of the artist’s gesture.

“Breuer is exploring the materials,” commented Virginia. “How far can he take them? How far can he go?”

Untitled (C-1159), 2012, Marco Breuer. Chromogenic paper, burned, 11 3/4 x 9 3/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Purchased with funds provided by the Photographs Council, 2014.9.8. © Marco Breuer

Process and Subject Are One

Process and subject are symbiotic for many of the works in Light, Paper, Process: the way they were made determines what they depict, and what they depict determines how they were made.

Matthew Brandt incorporates the elements of his subject into the making—or unmaking—of his photographs. For a series depicting Rainbow Lake in Wyoming, he laid developed prints face down in lake water, which ate away the emulsion in unpredictable ways.

Rainbow Lake, WY A4, negative 2012; print 2013, Matthew Brandt. Chromogenic print, soaked in Rainbow Lake water, 30 x 40 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Purchased with funds provided by the Photographs Council, 2014.16.2. © Matthew Brandt

In the series Dust, depicting demolished buildings, Brandt incorporated dust from the depicted sites into his emulsion—dust from a Trader Joe’s where Schwab’s Pharmacy once stood, dust from a parking lot that replaced a Mathers Department Store. Brandt’s life-size contact print of a prehistoric wolf at the Page Museum features tar from the nearby La Brea Tar Pits; his salted-paper portraits incorporate symbolic fluids, such as breast milk, saliva, and tears.

Will, 2007, Matthew Brandt. Salted paper print with tears, 2 5/8 x 2 in. Courtesy of the artist, Yossi Milo Gallery, New York and M+B Gallery, Los Angeles. © Matthew Brandt

To develop her contact prints, Lisa Oppenheim uses the source of light that the print depicts. For pictures of the sun, she uses sunlight; for the moon, moonlight; and for smoke, a flame. Developed using a flame, her series La Quema features plumes of smoke cropped and enlarged from a Manuel Álvarez Bravo photograph of a kiln. The prints are paired with same-size terracotta tiles produced in a Mexican kiln much like the one shown in his photo, but cropped out in hers.

A Drive to DIY

Because they focus on process over perfection, the photographers in the show approach their work as an impassioned, physical quest.

Chris McCaw customizes his own cameras, affixing military reconnaissance lenses so they function like magnifying glasses. When he points the camera at the sun over the course of several hours—often in remote locales to which he has lugged his massive equipment—the sun sears its path into sheets of enlarging paper, which he loads into his camera instead of film, creating gashes that cast their own shadow within the frame.

Sunburned GSP #555 (San Francisco Bay), 2012, Chris McCaw. Gelatin silver paper negative, 8 x 10 in. Courtesy of Stephen Wirtz Gallery San Francisco. © Chris McCaw

Working in the field, John Chiara affixes photographic paper to the back of custom-built large-format camera with tape. Guesstimating exposure times, he returns to the studio with the paper rolled tightly into a length of PVC pipe, into which he pours developer and stop bath. This results in unpredictable streaks and abnormalities that enhance his evocative landscapes. One print even features a large blotch created by drips of the photographer’s own sweat. For Chiara and the other photographers in Light, Paper, Process, such clues to the work’s making are an important part of the image itself.

Sierra at Edison, 2012, John Chiara. Chromogenic photograph on Kodak Professional Endura Metallic paper, 50 x 72 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Purchased with funds provided by the Photographs Council, 2014.8.4. © John Chiara

“Some photography today tends to be slick and have very high production values. Here there’s a roll-up-your-sleeves approach, a DIY mentality,” Virginia commented. “There’s a driven quality to the work—as if each of the artists is saying, ‘I’ve got to figure this out, and I’m not going to shy away if it’s too difficult. I can make it work.’”

Like the 19th– and 20th-century photographic experiments that preceded them (and selections of which are included in the show’s first gallery), the works in Light, Paper, Process have a sculptural, tactile presence that defies reproduction online. Remarkably varied in texture, color, scale, and edge, these photographs engage deeply with physical world, and with the magic that can arise when light meets paper.

_______

To learn more about the exhibition Light, Paper, Process, watch video profiles, and hear audio commentary on key images, visit the exhibition webpage.

Comments on this post are now closed.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks