One of the highlights of the exhibition Bouchardon, Royal Artist of the Enlightenment (January 10–April 2, 2017 at the Getty Center), was an extraordinary series of drawings and prints depicting street peddlers who populated Paris in the eighteenth century. A leading French sculptor and draftsman of the time, Bouchardon depicted his models, close-up and at full length, wearing the garb and holding the tools typically associated with their trade. Known as “The Cries of Paris,” Bouchardon’s series, containing five sets of twelve prints each, is named for the cries that such street vendors shouted to peddle their wares and the services they offered to all. Just imagine what a cacophony must have reigned in the streets of Paris!

This genre of imagery was very much in vogue with artists and collectors in the late 1730s, a time when subjects from everyday life in the vein of seventeenth-century Dutch painting were experiencing renewed popularity. Dating from circa 1737, Bouchardon’s drawings and the prints based on them (published in Paris between 1737 and 1746) constitute a poignant record of the laboring class. These “anonymous portraits” are all the more powerful as they depict real people―rather than types—with astonishing immediacy. The fact that most of the tradesmen and tradeswomen appear strongly individualized suggests that Bouchardon found them visually compelling as genuine people, endowed with unique facial features and expressions and, most of all, a presence of their own. These figures seem to matter in their own right, not just as archetypes of their professions.

The drawings are all drawn in purple-red chalk to a high degree of finish, with the medium generously applied to the paper. The corresponding prints followed them faithfully, as shown by a comparison between the drawing of a Rabbit-Pelt Seller (below) and its interpretive print. The count de Caylus, a respected amateur printmaker, used an etching needle to render the draftsman’s outlines to scale and with sensitive precision; however, he retained Bouchardon’s original orientations, which resulted in the compositions being reversed in the print. The etching lines were then reinforced by another printmaker with a burin, which served to work out the surfaces and build up the shadows through cross-hatching, where Bouchardon had used simple hatching only.

With side lighting―consistently coming from the left in the drawings―revealing forms forcefully in the third dimension (as could be expected from a sculptor), Bouchardon carefully orchestrated his sitters’ poses with their attributes, employing props on occasion. This strongly suggests that he worked in the controlled environment of his studio at the Louvre.

Rabbit-Pelt Seller (Peaux de Lapin), Edme Bouchardon, from Études prises dans le bas peuple ou les Cris de Paris (Studies drawn in the lower folk or the Cries of Paris), 1737–46. Drawing, left, from leather-bound album including 60 original red-chalk drawings by Edme Bouchardon. The British Museum, London. Image © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved. Print, right: Etching with engraving by comte de Caylus and Étienne Fessard after Edme Bouchardon. The Getty Research Institute, 2015.PR.2

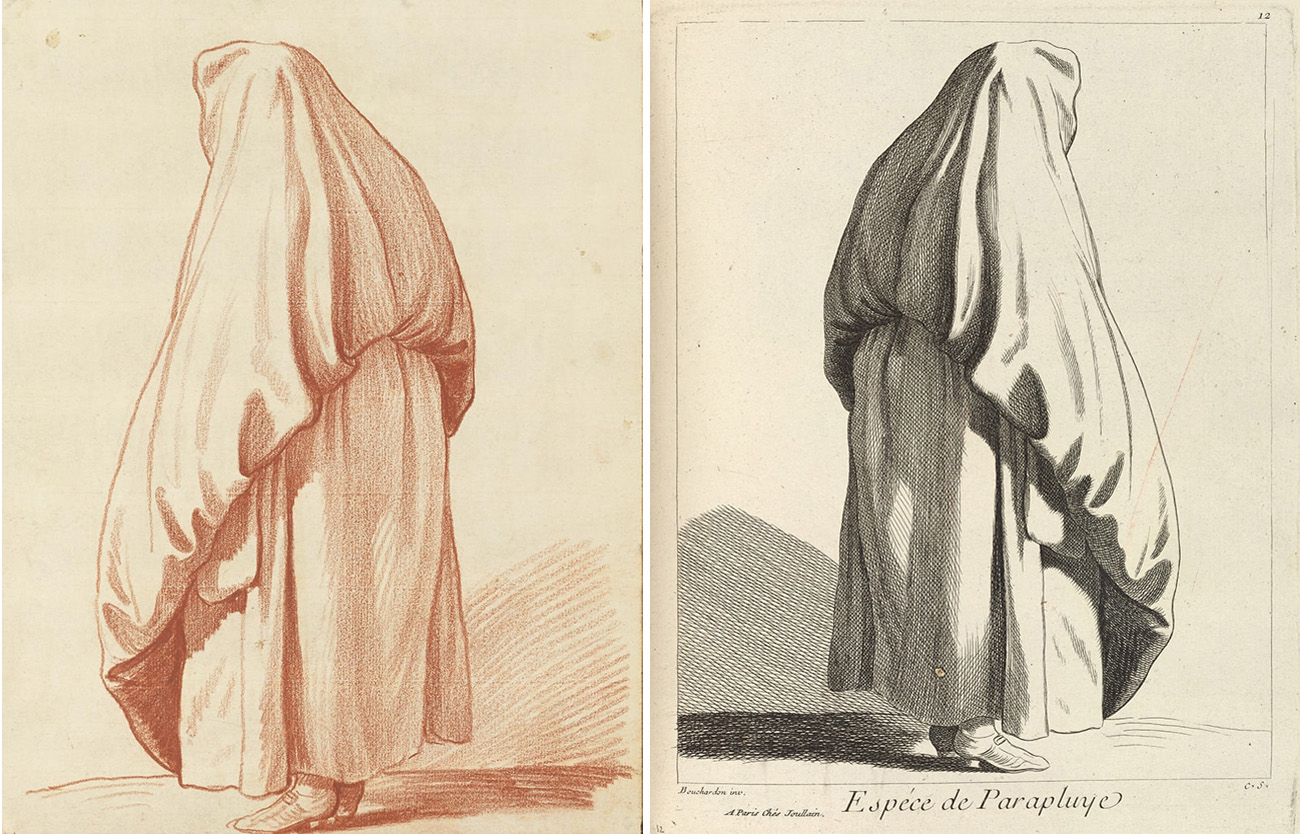

Even though he did not intend to realize the figures as statues, they feel so tactile and three-dimensional that he appears to have conceived of them as if they existed in the round. A Kind of Waterproof Cloak, for example, seems little more than a pure exercise in formal experimentation. While the motif may be unexpected and amusing, Bouchardon was seriously interested in the powerful definition of form in space and the careful modulation of light. Although the majority of his models seem absorbed in their occupation, and thus do not acknowledge the draftsman’s presence, a full third of the subjects look straight at the viewer. A connection is thus established, and the figures seem uncomfortably, humanly close.

A Kind of Waterproof Cloak (Espèce de Parapluye), Edme Bouchardon, from Études prises dans le bas peuple ou les Cris de Paris (Studies drawn in the lower folk or the Cries of Paris), 1737–46. Drawing, left, from leather-bound album including 60 original red-chalk drawings by Edme Bouchardon. The British Museum, London. Image © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved. Print, right: Etching with engraving by comte de Caylus and Étienne Fessard after Edme Bouchardon. The Getty Research Institute, 2015.PR.2

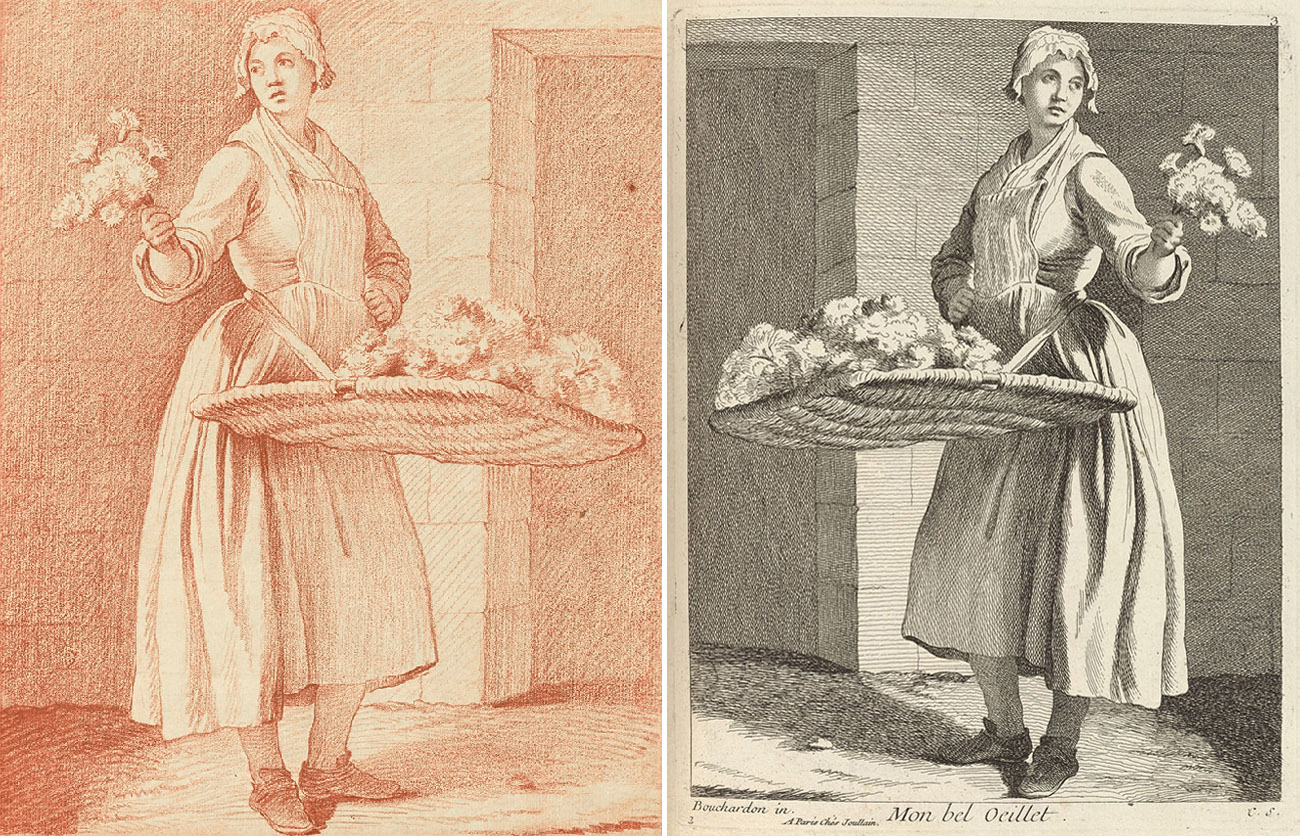

Apparently, not all were at ease while posing for the artist, which must have been an uncommon experience to these non-professional models. Nor does it seem that Bouchardon either empathized with all of them in equal measure. They harbor a wide range of expressions, from the rascally complicity of the windmill seller to the sweet boyishness of the hurdy-gurdy player, from the pensive melancholy of the young chimney sweep to the cautious mistrust of the barrel-organ operator. Not all his characters are performing obviously productive tasks―in fact, real effort is rarely shown. There is, besides, indeterminacy about certain trades. For example, the specific value added by the figure represented in Woman from the Mountains is not manifest, while that of the flower seller in My Pretty Carnation may be more than it seems, flower sellers being frequently arrested for prostitution.

My Pretty Carnation (Mon bel Oeillet), Edme Bouchardon, from Études prises dans le bas peuple ou les Cris de Paris (Studies drawn in the lower folk or the Cries of Paris), 1737–46. Drawing, left, from leather-bound album including 60 original red-chalk drawings by Edme Bouchardon. The British Museum, London. Image © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved. Print, right: Etching with engraving by comte de Caylus and Étienne Fessard after Edme Bouchardon. The Getty Research Institute, 2015.PR.2

Bouchardon’s original drawings, generously loaned by the British Museum for the exhibition, are bound in a volume, so only one of them can be presented at a time. By contrast, the prints, loaned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, are in loose sheets. A bound volume of the prints was acquired by the Getty Research Institute on the occasion of this exhibition, and has been fully digitized. The British Museum drawings and Getty Research Institute prints are accessible in a digital interactive, available both within the exhibition and online, thanks to a special viewer that you can discover here long after the exhibition closes.

Comments on this post are now closed.