Subscribe to Art + Ideas:

“It’s really quite astonishing how often, in looking at some of the works of these Japanese American photographers, how simple the subject is, and yet how graceful its rendition is.”

At the turn of the 20th century, the Japanese population in Los Angeles was growing rapidly. At the same time, photography was becoming more affordable, accessible, and popular. Scores of Japanese Americans were avid photographers in this period, and by 1926 the community was active enough in LA to form a club, the Japanese Camera Pictorialists of California, centered in the Little Tokyo neighborhood. However, as the US entered WWII and the military displaced and incarcerated Japanese Americans from the West Coast, their community splintered. These photographers were forced to leave behind their cameras, negatives, and photographs, many of which were destroyed. As a result, much of the history of this group was lost or forgotten for decades, until the early 1980s, when art historian Dennis Reed began working with Japanese American families to preserve and display these artworks.

Getty recently acquired 79 photographs by Japanese Americans from the Dennis Reed collection as well as 75 additional photographs from the families of these artists. In this episode, Virginia Heckert, curator in Getty’s Department of Photographs, discusses these works and the history of this artistic circle.

More to explore:

Japanese-American Photographs, 1920–1940 Google Arts & Culture exhibition

Transcript

JAMES CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, President of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

VIRGINIA HECKERT: It’s really quite astonishing how often, in looking at some of the works of these Japanese American photographers, how simple the subject is, and yet how graceful its rendition is.

CUNO: In this episode, I speak with Getty curator Virginia Heckert about early 20th century Japanese American photographers in Los Angeles.

The Getty Museum recently acquired seventy-nine photographs made by Japanese American photographers, many of them members of the Japanese Camera Pictorialists of California, a photography club in Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo neighborhood dating back before World War II.

These photographs had been stored for decades and were gradually rediscovered beginning in 1981, when Dennis Reed, an artist, professor, and photography collector, who had learned about this fascinating chapter of art in Los Angeles, received a phone call from the niece and heir of Shinshaku Izumi, one of the members of the club. That initial call led, some three decades later, to a tour of Reed’s collection by Getty curator of photographs, Virginia Heckert, who was so moved by the photographs and their story that she turned to Reed and said that if he was ever willing to part with his collection, she wanted him to come to the Getty first. And a few years later, he was and he did.

I recently spoke with Virginia about these photographs, their makers, and the Japanese Camera Pictorialists of California.

Virginia, it’s great talking with you.

HECKERT: And it’s a pleasure to be here talking to you about this group of photographs.

CUNO: Now, tell me about the Japanese Camera Pictorialists of California photography club and how and when it got started.

HECKERT: So it got started 1923 by a photographer named Kaye Shimojima, who left Japan in 1907, went first to San Francisco, then to Sacramento, and then came to Los Angeles in 1923 and started a camera club for Japanese Americans in Little Tokyo. It was informal. Members would gather, share their images, critique each other’s work and tgo on outings together. Two years later— three years later, actually, 1926, it became more formalized. And the following year, 1927, it changed its name to the Japanese Camera Pictorialists of California.

There is one photograph in the Dennis Reed Collection of Japanese American photographs by Shimojima. And you can really see that he was very masterful in the way that he composed his images and the kind of scope of them. This image is called Dusty Trail, and it shows a herd of sheep heading up a hill with a very atmospheric lighting coming through the tree branches. He was a very exacting and inspirational photographer, something like the kind of master teacher for all of these other photographers who were in the club.

CUNO: So what was a camera club?

HECKERT: It was an informal or a formal group of like-minded individuals who gathered on a regular basis. They would share work with each other, critique each other’s work, and they would also go on excursions to photograph together. In many cases, these camera clubs were also ambitious enough to host regular exhibitions, sometimes annually, sometimes more regularly than that.

And some of them even published their own journal. And this was a good way to circulate information amongst members of the club in one city with members of a club in another city. And this was both nationally and internationally.

CUNO: Were these photographers all self-taught?

HECKERT: That’s a great question, actually. Photography was not taught as it is today in colleges and universities as an art form. It would be more a trade that people would learn, you know, on the job, apprenticing with a photographer. So yes, I would say all of these photographers were self-taught. I believe there is one instance where one of the photographers—and I can’t recall the name—was enrolled at Art Center, but it would not have been for photography. So he had this interest in art.

In addition to photo clubs, there were also art clubs. And those art clubs, especially among the Japanese American community, would perhaps look at poetry and painting. And so blending very specific Japanese-influenced forms of these arts.

CUNO: All the photographers in the club, did they all immigrate from Japan to California? And if they did so, did they come with knowledge of photography, or did they learn their photography in California?

HECKERT: All of the members of the club were Japanese American. And they were of differing ages when they emigrated from Japan to the United States. Some of them were young boys joining their fathers and older brothers, often in the agricultural industry. And many of them had very sort of blue-collar jobs as dry cleaning businesses, dry goods stores, as gardeners.

So it would be hard to say definitively or for all of the photographers in this group, whether they had come from Japan with knowledge of photography or whether they picked up that knowledge here. Because I think it depends largely on the age at which they came to the United States. And I would imagine that a lot of them, sort of in forming friendships, learned of the possibility of being more dedicated to a form of expression like photography from those who had already made a commitment to it.

CUNO: What was the status of photography in Los Angeles at the time?

HECKERT: Well, as we know today, Los Angeles is a fantastic place to be an artist, to make art. And it was no different in the 1920s. There were already a number of very well-established photographers, most of them belonging to camera clubs.

A name that everybody will know is Edward Weston. He was one of the founders of Camera Club of Los Angeles, I believe it was. And that was a very elite group. But photography was pretty widespread as a form of art, in addition to a form of communication.

CUNO: Now, these Japanese American photographers had centered their life and their art in Little Tokyo. Describe Little Tokyo for us, where it is in Los Angeles, how it came to be called Little Tokyo, and what its social and commercial character was like.

HECKERT: Well, historic Little Tokyo is just north of downtown. It’s bordered by East 1st Street on the south and the 101 freeway on the north, and in between North Alameda and Los Angeles Streets. People familiar with art institutions like the Japanese American National Museum and the Geffen Contemporary at MoCA, or even Hauser & Wirth Gallery will have passed through Little Tokyo.

Apparently, it got its name from a former sailor, a Japanese sailor, who opened a restaurant on East 1st Street. And this really became a magnet for the male immigrants who were coming from Japan for work opportunities, to move to boarding houses on East 1st Street and begin to populate this area.

Around 1900 there were just a few thousand Japanese residents. By 1920, about 20,000; and by 1942, almost double that. And it became a really thriving community with its own religious institutions, civic institutions, schools, and even its own newspaper. For Japanese, it created a sense of community. But for those who were perhaps not Japanese, there was the view that it was a ghetto, that it was over-crowded, that it was dangerous and not a very safe place to live.

CUNO: Well, you raise the fact that there was a newspaper in the community. What role did the newspaper Rafu Shimpo, L.A. Daily Japanese News, play in the community’s cultural life?

HECKERT: Well, Rafu Shimpo was actually the first Japanese American newspaper, started in the United States in 1903. And I believe that it’s still published today. One of the eventual members of the Japanese Camera Pictorialists of California became the artistic director of the paper in 1918 or so. And he came up with the idea that it would help drive subscriptions if the newspaper could organize a photo competition.

Which took place in 1924. It was for amateur photographers, and they even produced a small catalog that published twenty-five photographs. And this really became an incentive for more people then to join the original version of that Japanese Camera Pictorialists of California club. And those exhibitions occurred on an annual basis.

CUNO: There was a camera club in Seattle called the Seattle Camera Club. Did it have any relationship to the Los Angeles club, or was there one in San Francisco, also?

HECKERT: Yes. Yes, there were similar clubs in San Francisco and in Seattle. And they were Japanese American photography clubs. The club in Seattle did not restrict itself to Japanese Americans. In fact, it welcomed non-Japanese members, as well as women members.

And members would correspond with each other. They also submitted to each other’s annual exhibitions and often published in Seattle, the camera club, which was started by a man named Dr. Koike. He published a journal, as well. They learned very much from what the members of the club wrote in that journal.

CUNO: Why did they call their club pictorialism? Or why did they include that term in the name of the club? What did it mean then?

HECKERT: Pictorialism in photography is a term that’s been around, actually, for quite a long time. Photography was invented about 1839, or its invention was announced to the world then. It was mostly, you know, gentlemen of leisure with a background in science and art who practiced it. But already by the 1860s or so, there were practitioners who wanted to distinguish themselves from commercial photographers or professionals, so they introduced this idea of a pictorial approach to the medium.

This really solidified around 1900, especially not only for certain practitioners to distinguish themselves from commercial photographers, but also from amateur photographers. Kodak was a firm that produced cameras that were very inexpensive. Everybody had a camera, everybody was a photographer, much like we are all photographers with our cell phones in our pockets now.

And so a number of clubs were formed, societies were formed, with various names. In England, it was The Linked Ring; in New York, led by Alfred Stieglitz, it was the Photo Secessionists. And their goal was to add intention to their work and an artistic motivation, which was often very evident by certain techniques like soft focus or dramatic lighting or themes that were typical of painting. For example, nudes, ambitious landscapes.

And very important also was the fact that each print would be handcrafted and show the craftsmanship of an artist, and not just photography as a mechanical medium.

CUNO: Did the photographers in Los Angeles know of people in New York, like Alfred Stieglitz?

HECKERT: Yes. I’m quite certain they would’ve known, because there were journals that were circulating, annuals that were circulating. It was very easy to get information, to share information about photography.

CUNO: I gather that this relates to the Japanese aesthetic of mono no aware, which means something like that which stirs cultivated sympathies by touching them with beauty, sadness, and awareness of ephemeral existence. In other words, sort of a momentary beauty of vulnerable things.

Is this something that’s characteristic of pictorialism? Would the same definition be applied to pictorialists in New York or in London or in Germany, for that matter?

HECKERT: I do think it’s more specific to the Japanese American aesthetic. My understanding of the term also has to do with this sense of temporal beauty. And it’s really quite astonishing how often, in looking at some of the works of these Japanese American photographers, how simple the subject is, and yet how graceful its rendition is.

It may be the curve of a road or the placement of figures in a landscape, or even in one image by a photographer named Izumi, it’s the shadow of a bicycle wheel, where you only see a fraction of the bicycle, which is heading out of the picture. So this idea of fleeting beauty, I think is something that is unique to the Japanese American aesthetic.

CUNO: I read somewhere in the catalog for another exhibition of the work that there’s a Japanese concept of something called wabi, W-A-B-I, a kind of existential emptiness. And there’re references made to raked dry gardens of Zen Buddhist temples. Is that something that you would associate with pictorialism?

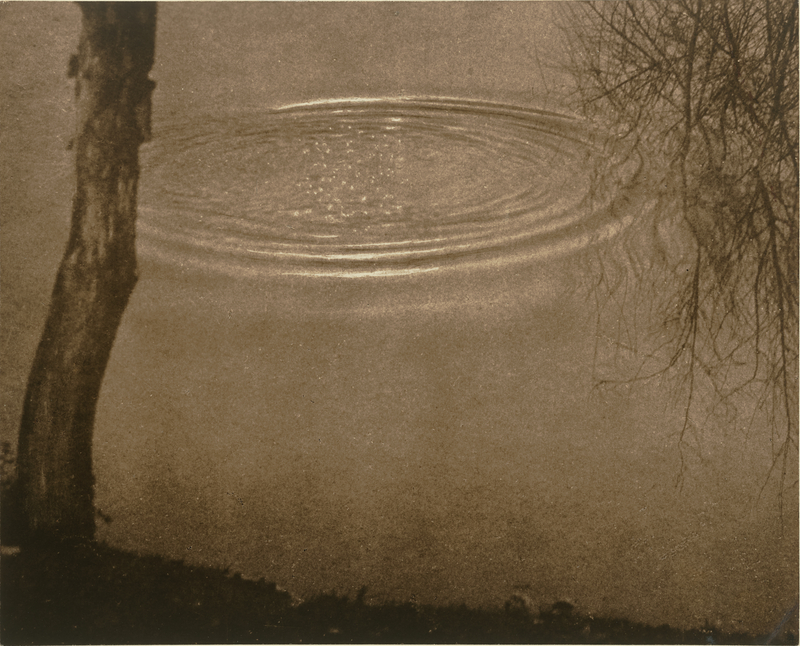

HECKERT: Again, I would say it’s specific to the Japanese American pictorialists, because there is this sense of pared-down simplicity and austerity to the work. The ripple of a stone being dropped into a body of water or a singular figure sitting in the landscape. It’s a sense of austerity, but not deprivation. You don’t feel that there is, for example, in that lone figure, he’s not lonely; he’s just alone and at peace with himself and with his surroundings. So again, I would say it’s very typical of the Japanese Americans, but not, in general, of pictorialism.

CUNO: Well, there’s this extraordinary photograph in the collection by an artist named Kira, showing a man seated on a— on a dam. Quite deliberately abstract, it seems. And it’s called The Thinker. Describe it for us and tell us about it.

HECKERT: It’s really a dramatic composition. This is the lone man, sitting not in the landscape, but it’s actually the Hollywood Dam, which looks very much like a concrete amphitheater with steps heading downward and a sweeping curve. And he feels sort of minute, seated there.

Apparently, the photographer, Kira, was trying to sell a camera to a customer of the store where he worked. And they went out to see how that camera would work, and Kira made this picture with the camera. And of course, I don’t know how long it took to develop the print, but the customer was so impressed that an image like that could be made that he did buy the camera.

CUNO: We’ve been talking quite a lot about natural beauty, but this manmade beauty because it’s a man sitting on a dam. The shadows that ripple up the stairs of the dam, suggesting kind of abstraction. Or the reverse of a ripple in a pond.

HECKERT: Yes. And I think this is another characteristic of the Japanese American aesthetic. This tendency to abstract or create semi-abstractions of both natural and manmade objects.

We’ve been focusing on pictorialism, but the period that is covered by the works in this collection is 1919 to 1940. And what you see happening during that time in photography is a movement away from pictorialism, towards modernism. And so there’s often the introduction of repeated shapes and patterns, more sort of dramatic and hard-edged lines, in the images. And I think that’s what you are beginning to see here in this image by Kira, is that shift, that move towards a more modernist aesthetic.

CUNO: I guess you could contrast it with Ota’s The Ripple, of 1933, which we may be more conventionally seen as a pictorialist photograph.

HECKERT: Yes. But again, what I do find so fascinating is that it’s not always so easy or even important to say that’s definitely pictorialist and that’s definitely modernist. There are works that would be hard to define as one or the other. There are others that are more obviously sort of fall into one category than the other. But I think sometimes that also has to do with the way the prints have been printed. For example, different techniques like bromoil techniques, which give them a richer, browner tone than, for example, an ordinary gelatin silver print.

CUNO: What about the landscape photographs of Hideo Onishi, from 1924 to 1926?

HECKERT: There is one in the Dennis Reed Collection called Sea Breeze. And when you first look at it, you’re not entirely sure what you’re looking at because there’s no horizon. You see waves rippling, but you also see some branches entering into the composition at the top and the bottom. And so what you really get a sense of is more the sort of— It’s almost like a meditation on what it must’ve felt to be in this space, with slightly rustling leaves, the movement of the water, and just the sense of great peacefulness.

Also it has a very typical Japanese composition. As I said, there is no horizon and it’s a vertical orientation, so it feels very much like a Japanese woodcut.

CUNO: Now, we’ve talked about other pictorialists and even modernist photographers working in Los Angeles, Edward Weston being one of them. There’s also Margrethe Mather. What relationship did they have to these particular Japanese photographers?

HECKERT: They did know each other. They did know each other. Weston, Edward Weston, a quintessential Los Angeles photographer, was one of the founding members of a club called The Camera Pictorialists. And this was a very elite club that people like Mather, Kales, and other photographers belonged to. They submitted their work for exhibition in Little Tokyo. In fact, Weston had three exhibitions in Little Tokyo.

He is convinced that many of the Japanese American photographers were influenced by his work, especially when he attended then a salon of photographs in the Los Angeles Museum at Exposition Park. And this is now the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. And he remarked that all the work was pretty mediocre, except those by the Japanese American photographers.. And he was convinced, as I said, that they had been influenced by his own work.

It’s really hard to tell, though, when you look at some of these compositions, whether it’s a piece of fruit or a vegetable, the way a head of cabbage has been sliced in half. And many people will know that these are all subjects that Edward Weston photographed. But many of the Japanese American photographers also used these as subjects, and so it’s hard to know, if you see a date of, say, 1928 or about 1930, who made that image first.

In fact, what I should say is that it was common practice for these members of camera clubs to all photograph the same thing. So nobody really owned a subject. Particularly if they went on a outing to the beach. They would all take photographs of waves. And each might be a little bit different and you might, say, prefer the horizontal versus the vertical orientation. But essentially, they were photographing the same things.

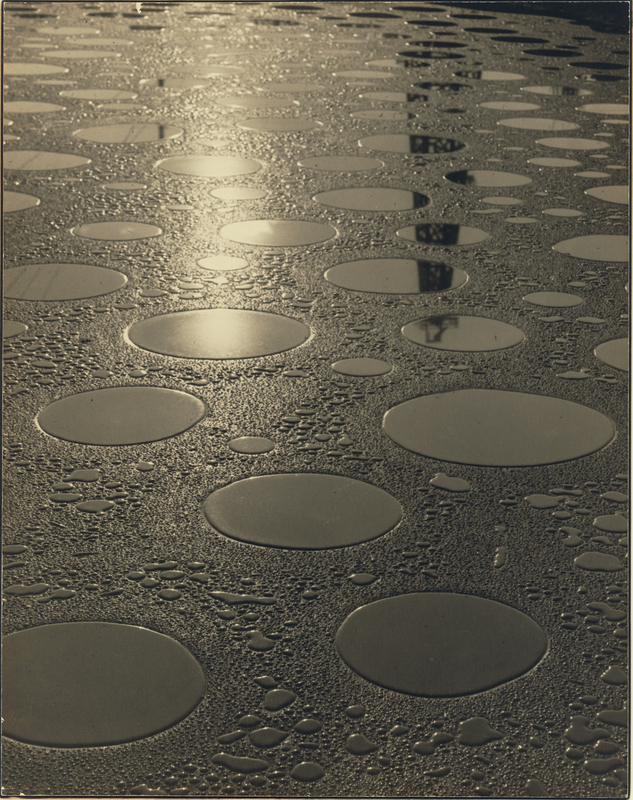

CUNO: They found beauty in what might seem to be compromised conditions of modernity. I’m thinking of Shigemi Uyeda’s Reflections on the Oil Ditch, which lends itself to a kind of abstraction because of the sort of islands of oil that float on the surface of this water. Describe it for us.

HECKERT: Well, this is a really terrific instance that brings us back to the importance of the fact that all of these photographs were brought together by one man, Dennis Reed, who in addition to the Shigemi Uyeda Reflections on an[sic] Oil Ditch finished print, also managed to collect a print of the larger negative from which this has been abstracted.

So in that widened view, you see a more industrial landscape. But in fact, without knowing that it’s an oil ditch, when the photographer chose to hone in on just these repeated patterns of circles on which the sun is reflecting, it really does become something that’s quite beautiful because of that abstraction.

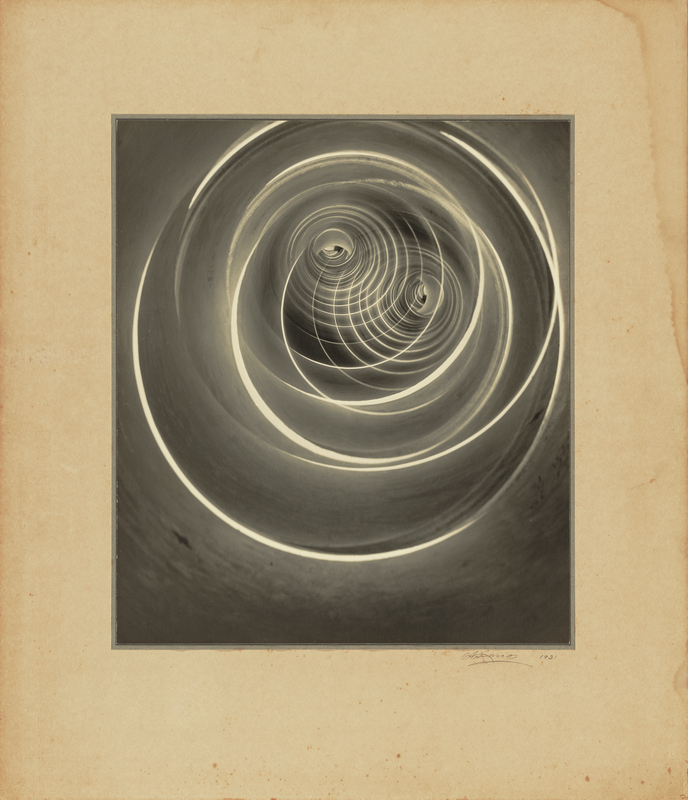

CUNO: I’m reminded of another Japanese photographer of the time, 1931, Asachi Kono, whose photograph is called Perpetual Motion, which seems as if it’s kind of an abstraction with a flashlight that is the lighted image that’s swirling around and around and around. And that brings to mind to me Germany in the 1930s. Is there a kind of relationship to the Bauhaus at all? And were they aware of the Bauhaus and the Bauhaus photographers?

HECKERT: I would say that the Japanese American photographers would be familiar with a variety of different approaches to the medium of photography through circulation of annuals in which their work would be published, as well as those of various other figures. I don’t know that there would’ve been a direct relationship between the Japanese American photographers in Los Angeles and Germany.

There were German collectors, there were German writers, there were German artists here in the area, but I don’t know to what extent there would have been interaction. What I can, though, say is that the work in general created during this period fits into this larger idea of the new vision, Neues Sehen, which was typical of Germany.

And the Bauhaus was part of that; but so, too, was New Objectivity, which was a more direct, straightforward approach to the object than was practiced by, say, Bauhaus artists.

CUNO: You made reference to something that made me think that there was interest in film in Los Angeles at the time. Of course, 1920, 1930. And many of them were German expatriates who came. And would the Japanese photographers have been interested in film? And would the film have been Japanese film, would it have been American film?

HECKERT: Jim, I wish I knew the answer to that question; it’s a really fascinating one. I don’t know. Something to explore.

CUNO: Well, I suppose it’s obvious, but what effect did the incarceration of the Japanese during World War II have on these photographers? Were many of them incarcerated themselves? And if they were, could they continue making photographs while they were in camp?

HECKERT: A number of the Japanese to immigrated to the United States for work returned to Japan. Those who stayed were confronted with incarceration in these internment camps. Cameras were seen as contraband, so they all had to leave their cameras, their photographs behind.

There was one photographer named Tōyō Miyatake, who was interned at Manzanar. And he managed to smuggle in a lens and a film holder, and sort of created his own makeshift camera, which he used to document camp life. Another of the Japanese American Los Angeles-based photographers, Hisao Kimura, was also at Manzanar, and he occasionally worked with Miyatake. But no, it was very unusual for photographers to be able to take cameras, or even any of their photographs, with them, once they were incarcerated.

Many of them, after that, came back, opened up new studios and continued to make photographs. But much of what they had created before was lost. And that’s actually what makes this collection that Dennis Reed has put together so remarkable, is that he, over the course of thirty-five years, assembled, put together the work of these many, many photographers, which would otherwise be forgotten because it was lost, destroyed, or just not deemed to be important.

CUNO: Well, tell us about the collector Dennis Reed, who he is and how he came to gather all these photographs together.

HECKERT: Well, Dennis is a retired professor from Los Angeles Valley College, where he taught for forty-two years. He taught design, photography, and photo history. He also ran the college’s art gallery and organized exhibitions.

In fact, one of the exhibitions that he organized in 1982 was of Japanese American photographers. And this is just one year after he sort of discovered that there was this unique pocket of artistic creation, creativity here in Los Angeles, and he just, he went whole hog. He just got so excited about discovering and learning more about these Japanese American photographers that he put together a list of the names of Japanese who were located in Little Tokyo in the 1920s, and had his students help make cold calls to see if any of them had a father or a brother who was a photographer. And slowly, by this kind of detective or meeting of one photographer leading to the meeting of the family of another photographer—

Of course, when Dennis was looking at this work in the 1980s, early 1980s, many of these photographers were already either dead or quite elderly, in their seventies or eighties. He only met a handful of them, but he did meet many of their family members.

And Dennis actually has been well known to the Getty Museum. We have a longstanding relationship with him. In 1994, the Getty and the Huntington Library and art gallery jointly organized an exhibition called Pictorialism in California: Photographs 1900–1940. So this interest in pictorialism specific to California has always been a part of what Dennis has looked at as a collector.

I mentioned that he, you know, taught; but with his great sort of detective work and expertise, he is a respected historian, especially of this material.

CUNO: How was it that we came, the Getty came to acquire these photographs from him?

HECKERT: I mentioned that Dennis organized an exhibition in 1982 for the art gallery at L.A. Valley College. Over the years, he’s organized three or four exhibitions based on material that he has both located with the families of photographers, and in some cases, really rescued by acquiring it from these families. So his knowledge is based both on the materials that he himself collected, but that he’s also located at other institutions.

He was to organize an exhibition for the Japanese American National Museum, on this subject of Japanese American photography between 1920 and 1940. That exhibition was called Making Waves, and it took place in 2016. Several of the curators of the Getty went to see the show. I had a personal walkthrough of the exhibition with him.

And I just blurted out, I said, “Dennis, I know a lot of these photographs are in your collection.” And I said, “If you’re ever wanting to part with that collection, please come to the Getty first.” And sure enough, he did. But he wasn’t ready to part with the collection for a couple of years. The exhibition was in 2016, and we finalized the acquisition in 2019, so just last year. What I wanna say also about that collection of seventy-nine photographs is that the majority of them are photographers based in Los Angeles.

And let’s see. I have the numbers here. Thirty-seven different photographers, twenty-two of them are Los Angeles-based photographers, or were Los Angeles-based photographers; seven from San Francisco; one from San Diego; six from Seattle; and one from Honolulu.

What was also interesting, any time we make an acquisition, we have to see what’s already in the collection. And of course, nobody thought we would have any Japanese American photographs. But we did, in fact, have nine photographs, including seven by Kira, the man who made the picture called The Thinker.

Dennis very kindly and generously offered to introduce us to the heirs of some of the photographers. An so I had the opportunity to meet five different families. And they were interested in donating photographs to the Getty Museum, to better represent or more fully represent the work, in this case, of their grandfathers in the Getty Museum’s collection, finding it something of an honor that the Getty Museum would be interested in acquiring this work. We, on the other hand, felt it a huge honor to be able to represent these photographers’ works.

CUNO: Now, you talked about the relationship between these photographs and photographs by Japanese and Japanese American photographers already in the collection of the Getty, but you had a concerted effort to build the collection of Japanese photography beyond that. Tell us about that.

HECKERT: The Getty Museum’s department of photographs was established in 1984. And the emphasis at that time was the first 100 years of the medium, as a largely Western and American art form. Of course, you know, as years went on, we wanted to expand beyond those boundaries. We now collect in the twentieth and twenty-first century. We’ve collected work from South America, from Africa, and from Asia.

The initiative to increase our holdings of Japanese, Chinese, and Korean photography was really begun by Judy Keller, who was the senior curator from about, oh gosh, 2010 to 2015. She really built up our holdings of Japanese photography in particular.

And in fact, one of the things that I would like to do is to learn more about what the difference is between works made in Japan around this time and works made by Japanese American photographers on the West Coast. It seems to me that there was more of an influence, or there as greater influence, of Surrealism in Japan on some of those artists, at least in those that are represented in our collection. For example, Kansuke Yamamoto and Osamu Shiihara. These artists have decidedly Surrealist influence in their work, which is not the case with the Japanese American works that we acquired through Dennis Reed.

CUNO: Well, what’s next for these particular photographs, the ones you acquired from Dennis Reed?

HECKERT: Well, Dennis, with his multiple hats that he wears, was very thorough in providing us with provenance and exhibition and publication history. But one thing I am very eager to do, once we are able to go back and look at the library, is to take a look at the variety of camera almanacs and yearbooks and periodicals that were published during this time period of 1920 to 1940, and just peruse the pages and see what was the relationship between works by the Japanese American photographers represented in our collection and photographers from Europe, from other parts of the United States, from Japan.

Whose work might sit side-by-side with another photographer’s work in these books, and therefore, show us that there would be knowledge of that work? What kind of influence might we see? Dennis has done a great job on several occasions already, of organizing exhibitions of Japanese American photography; but I would kind of like to broaden that out and learn more about this period of change, of transition from pictorialism to modernism, and see what nuances that transition had, when practiced on the West Coast by California-based photographers, by Japanese American California-based photographers, by New York-based photographers, by European photographers, and by Japanese photographers.

So yes, I would say an exhibition and book project, but a little bit further down the road. Not just yet.

CUNO: Well, what about Google Arts & Culture? I know that we’ve got various exhibitions online with them. Would this be a opportunity to show these photographs then with the public?

HECKERT: That’s a great reminder that a Google Arts & Culture exhibition has already been done with a handful of these photographs, perhaps more like a dozen of the photographs, and a great opportunity for people to see these beautiful images.

CUNO: Thank you, Virginia. It’s always fun talking about photography with you. And especially, thank you for sharing this great new acquisition with us.

HECKERT: Well, thank you, Jim, for this opportunity to talk about these works.

CUNO:This episode was produced by Zoe Goldman, with audio production by Gideon Brower and mixing by Mike Dodge Weiskopf. Our theme music comes from the “The Dharma at Big Sur” composed by John Adams, for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003, and is licensed with permission from Hendon Music. Look for new episodes of Art and Ideas every other Wednesday, subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and other podcast platforms. For photos, transcripts, and more resources, visit getty.edu/podcasts/ or if you have a question, or an idea for an upcoming episode, write to us at podcasts@getty.edu. Thanks for listening.

JAMES CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, President of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

VIRGINIA HECKERT: It’s really quite astonishing how often, in looking at some of the works of th...

Music Credits

“The Dharma at Big Sur – Sri Moonshine and A New Day.” Music written by John Adams and licensed with permission from Hendon Music. (P) 2006 Nonesuch Records, Inc., Produced Under License From Nonesuch Records, Inc. ISRC: USNO10600825 & USNO10600824

See all posts in this series »

I enjoyed this podcast very much