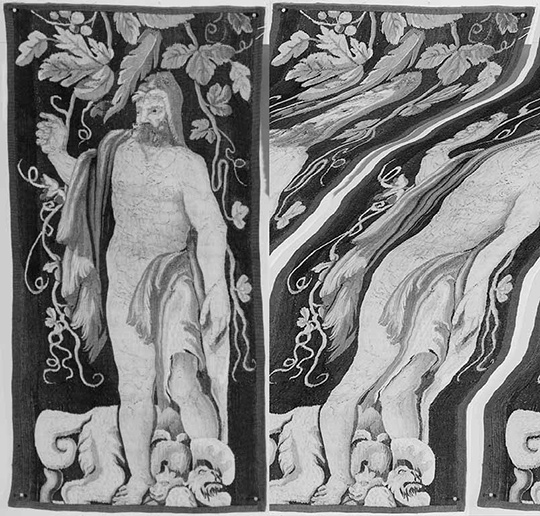

Crop of a digitally decayed scan of a page from Ceremonies et coutumes religieuses de tous les peuples du monde, representeées par des figures dessinées de la main de Bernard Picard, avec une explication historique, & quelques dissertations curieuses, 1723–1743. The Getty Research Institute, 1387-555

At the Getty Research Institute we have been working tirelessly for the past few years to digitize and provide access to our collections, which range from the 15th century to the present and include books, photographs, manuscripts, archives, works on paper, audiovisual materials, and more.

As the demand for digitization increases, so do the number of digital files—and thus the storage and systems needed to manage those files. Right now our repository contains almost 570,000 files taking up 52 terabytes. Additionally, more and more of the collections we acquire contain born-digital material such as digital photographs, audio, video, and documents on hard drives and CDs.

Last year, we implemented digital preservation software to help identify what we have, select material to preserve for the long term, and ensure that the files don’t degrade over time. As we moved old files into the system, I encountered my first few instances of file corruption, which made it clear that we needed more safeguards for our files.

The Fragility of Digital

It’s been said that digital files are more fragile than physical ones. While you are still able to view family photographs printed over 100 years ago, a CD with digital files on it from only 10 years ago might be unreadable because of rapid changes to software and the devices we use to access digital content.

Most physical materials can survive a lot of abuse and still remain legible. If a corner is torn off a photograph or a page falls out of a book, you can still access the majority of the content. With digital files, however, degradation is more random and can sometimes lead to complete loss where the file can’t even be opened.

As one example, digital files from the Research Institute’s collection of black and white tapestry photos were created around 2002 and had been sitting on a server (or more likely a series of servers) since then. Some twelve years later, of the 5,000 files from this collection, ten were corrupt to the point where they couldn’t be recovered. That’s ten files lost simply from sitting on a server over time.

See the wavy tapestry photo below, in which Hercules has transformed from strapping hero to snakelike monster. In this instance, we still have the original photograph so could rephotograph it, but the same isn’t true for born-digital files, which have no physical incarnation.

Digital decay in action: A digital scan of a tapestry photograph as originally saved (left) and after corruption over time. Hercules and Nemean lion from Study photographs of tapestries. The Getty Research Institute, 97.P.7

Preserving Digital Files at Home

If you’re anything like me, you might start to panic and wonder how you’ll ever keep your files safe. Before you start frantically printing out all your photos and documents, read on. The Library of Congress comes to the rescue with their resources on personal archiving. They list four steps to the process: identify what you have, decide what to preserve, organize the content, and make copies.

I would add one more step, which is to make sure your files are in widely used formats, such as TIFF for images, DOC or PDF for documents, and so on. Deciding to save files in standard formats, or resaving older files into these formats, is one of the best choices you can make, because it helps ensure that there will be software to read the files going forward. These steps apply whether you’re working with hundreds of files or tens of thousands.

Preventing Decay at the Getty

The Getty Research Institute’s investment in Ex Libris’s digital preservation software, called Rosetta, has helped us address most of the four steps mentioned above. We’ve identified how many files we have and in which formats. The system pulls out technical information from the files, and we assign descriptive information when we add files to the database that allows us to keep them organized and findable.

The system goes one step further to ensure file integrity by creating a sort of fingerprint for the file, called a “checksum,” which is a numerical value based on the number of bits in the file. On a regular basis, we can regenerate these values from any given file and compare them to the values created when the file was added to the database. If the numbers don’t match, we know something has happened to the file and we can restore it from our backup copy—no more wavy tapestries!

In order to keep current with this ever-changing field, Getty Research Institute staff attend an annual, international advisory meeting for Rosetta. This is a great time to brainstorm with colleagues and to get inspired by a community of people working together to keep our cultural heritage preserved into the future.

For more resources on file preservation, see the Library of Congress’s excellent Digital Preservation website.

Hello. I haven’t found a word on raw capture or DNG. The showed images seems to come from flatbed scanners not from DSLR and that is not specified in the article. Doesn’t mention that from the first days of digital capture, with flatbed and film scanners, the file type for master file has always been TIFF.

Saludos

Jose Bueno

Thanks for the comment Jose. Our current practice is to use DSLR for our digitization, almost exclusively. We capture in RAW and output to uncompressed TIF as our preservation master format. We do not use RAW or DNG for preservation because of their proprietary nature. The images included in this post are legacy images that were scanned at the beginning of our digitization efforts.