James Ensor’s Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889 was the audacious centerpiece of a gallery in the Getty Center’s West Pavilion. What’s on view in its place?

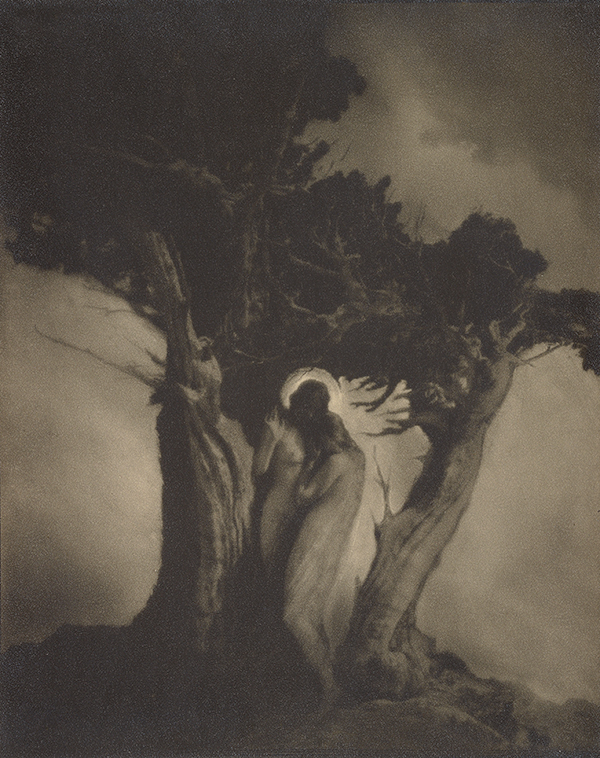

The Heart of the Storm, negative 1902; print 1914, Anne Brigman. Gelatin silver print, 24.6 x 19.7 cm. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Gift of the Michael and Jane Wilson Collection

Wandering the Getty Museum’s West Pavilion, you might miss Gallery W205. Tucked in a cozy corner, it’s easy to pass it by after a breathless viewing of Van Gogh’s Irises and other Impressionist works next door. But those in the know make their way to the gallery to view one of the masterpieces of the museum’s collection:James Ensor’s Christ’s Entry into Brussels, 1889. The roiling and raucous painting of a public procession dominates an entire wall of the gallery, leaving room for only a few other works, including paintings by Edvard Munch, Arnold Böcklin, and Fernand Khnopff.

But the playground has changed. “The bully,” as curator Scott Allan described Ensor’s vast, riotously aggressive painting, “has left the room.”

Christ’s Entry is housed through September 7 in the Special Exhibitions Pavilion for The Scandalous Art of James Ensor. Pictorialist photographs from the late 19th and early 20th centuries have taken its place in the gallery, and demonstrate the efforts made by artists to see photography recognized as a legitimate art form during this time. The Getty recently added a number of Pictorialist photographs to its collection.

On Pictorialism

Inside Gallery W205 at the Getty Center

I asked curator Scott Allan to explain how the addition of these photographs complement the existing paintings by Munch, Böcklin, and Khnopff:

My idea was to take advantage of the absence of Ensor’s Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889 and showcase the paintings in a new and interesting way, by comparing them with late 19th and early 20th century Pictorialist photographs that suggestively resonated with them in terms of subject and mood. It so happened that the Getty’s photography collection had a good number of examples for me to choose from, and the Museum’s photography curators were instrumental in helping me refine the selection. I think the pieces we picked play remarkably well with the paintings, and work to create a generally introspective, contemplative mood in the gallery, a mood very different than that of Ensor’s big loud bludgeon of a painting.

In an untitled photograph by George Seeley (American, 1880–1955), a model carries a lyre and may represent Orpheus. Pictorialist photographers often created highly idealized figure studies such as this one as a tribute to British poets of the Romantic movement.

Untitled, about 1903, George Seeley. Platinum print, 19.2 x 24.3 cm. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XM.163.3.

Many Pictorialist photographers were women, who achieved a level of professional acceptance that female painters generally did not. Work by Anne Brigman, Gertrude Käsebier, Sarah Choate Sears, and Imogen Cunningham make up the majority of photographs in the gallery. Among them is Brigman’s The Heart of the Storm (negative, 1902; print 1914), a haunting image of a woman protected by a twisted juniper tree and a guardian angel figure, and Gertrude Käsebier’s The Still Water (1904), which features a woman and child standing ominously at the water’s edge.

The Still Water, 1904, Gertrude Käsebier. Platinum print, 15.1 x 20.3 cm. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 87.XM.59.15.

So next time you visit the museum, take a peek at these photographs and paintings before the bully is back. It will give you an idea of what other artists were up to while Ensor was sketching skulls.

When will the remarkable Ensor painting return?

What an analogy to the recent Charlottesville’s march!

Hi Delores, Never fear, the painting returned to the West Pavilion at the Getty Center right after the Ensor exhibition back in 2014. Come see it any time! —Annelisa / Iris editor