J. Paul Getty is famous for being rich. Less well known are the facts and details about him as a person, a businessman, a collector, and a philanthropist.

Not surprisingly, visitors to the Getty Center or Getty Villa often leave with many of the same questions: How did he make his money? Why did he collect art? Did he buy all of this art himself? Did he have a hand in creating the Villa? The Center? Wasn’t he really cheap?

A new installation at the Getty Center, J. Paul Getty: Life and Legacy, addresses these frequently asked questions and many more. Created by a team of curators, archivists, educators, and designers, it offers a fuller picture of who J. Paul Getty was, and why the Getty exists as it does today.

In light of the new installation, I’ve recently updated the history pages of our website to share more of J. Paul Getty’s history. Having dug into his writings, photos, and archives, I learned a lot of interesting details about the man whose name is on my business card. Here are five of them.

Getty made his fortune in oil not once, but many times over.

J. Paul Getty refocused oil operations from Oklahoma to California in the 1920s. His very first oil rigs were among many other producers at the Santa Fe Springs oil fields. Oil fields near Los Angeles (Santa Fe Springs, 1927). Keystone-Mast Collection, UCR/California Museum of Photography, University of California, Riverside

J. Paul Getty was born into a wealthy family, but he made the vast amount of his money in the oil industry. He learned the business as a child, following his father into the Oklahoma oil fields during summer breaks from school, and witnessed his first oil strike at age 11. In his autobiography, he recalled it was a “unique thrill.”

After completing his studies, his father convinced him to try a summer prospecting for oil. Getty turned out to be an exceptional wildcatter. With a high tolerance for risk and a keen eye for reading the landscape for likely oil wells, he made his first million by the age of 23. And promptly retired.

But, having caught oil fever himself, in 1919 he returned to the oil company he had incorporated with his father, taking the helm after his father’s death in 1930. In the late 1940s, he negotiated a 30-year oil concession in the “Neutral Zone” between Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, meaning Getty Oil had exclusive rights to prospect for oil in the area. This was a huge risk at the time—oil had never been found there—and it paid off magnificently in the 1950s. Getty steered his company to become a global conglomerate that handled all aspects of oil production, from exploration to shipping. (His business ventures also included hotels and a company that manufactured mobile homes.) In 1957, Fortune magazine named him the “Richest Man in the World.”

Little-known fact: Getty learned Arabic so he could personally negotiate deals in the Middle East.

As a collector he appreciated classical beauty and art displayed in context.

Getty started seriously collecting art in the 1930s, but he was a lifelong collector. As a child, he collected marbles and stamps, and wrote about them in his diaries. (Keeping a record of his daily activities, including his art collecting, was a lifelong habit.)

Art collecting was a common practice among Getty’s wealthy peers like William Randolph Hearst and Norton Simon. And while Getty enjoyed the tax benefits that donating his art afforded him, he pursued collecting art with genuine passion. “My collecting over the years has been a labor of love,” he wrote in 1965.

Double Desk, about 1750, Bernard II van Risenburgh. Oak, mahogany, and various woods; gilt-bronze mounts. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 70.DA.87

Getty’s taste developed over time and was influenced by his travels—he routinely visited museums and historic sites while on business trips—and by trusted advisers. He delighted in a bargain, but he was also deeply interested in the technical quality of artworks and their provenance: “Exploring their whys and wherefores is exciting—as exciting as collecting itself.” He “never liked to follow the crowd” and felt “annoyed by the importance given to paintings by the majority of people.” Perhaps owing to his enjoyment of house museums, he believed that paintings and sculpture “should be displayed in surroundings of equal quality.”

His esteem for classical traditions of beauty and royalty also informed his tastes. He sought out Old Master paintings and considered it a “happy triumph” when he secured the acquisition of Rembrandt’s St. Bartholomew. Trips to Italy initially spurred his interest in collecting bronze and marble sculptures from ancient Greece and Rome (his favorite was the Lansdowne Herakles, on view at the Getty Villa). An extended stay in a New York City penthouse furnished with 18th-century French furniture made him a passionate admirer of decorative arts. He explained:

“The drama, adventure and thrills one experiences when one succeeds in acquiring a superb chair, divan, desk, or other piece of furniture that is not only an outstanding work of art, but was once used by a King of France, a Marie Antoinette, or a Pompadour. Believe me, history and its great figures do come to life.”

Little-known fact: Getty collected some 20th-century art. In 1933 he purchased ten paintings by the Spanish Impressionist Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida, attracted by the way they depicted sunlight.

He never visited the Getty Villa or the Getty Center.

Getty Ranch House Museum, Malibu, about 1957. Institutional Archives, The Getty Research Institute

Getty bought 64 acres of property in Malibu (now Pacific Palisades) in 1945, which included a ranch-style home. He converted that house into a two-story Spanish-style residence, including galleries to display his art collection. He used it for weekend getaways.

In 1954 the galleries of the Ranch House were opened to the public as the original J. Paul Getty Museum. Later, as his collection began to outgrow the Ranch House, he decided to build a major museum on his Malibu property, one that would be a replica of an ancient Roman villa. Primarily inspired by the Villa dei Papiri in Herculaneum, Italy, the Villa’s design draws on elements from other ancient villas as well.

Getty was deeply involved with the development of the museum at the Ranch House and the larger site that became known as the Villa. For instance, he approved all museum acquisitions until his death in 1976. But he never set foot in the J. Paul Getty Museum as an institution open to the public. With his business interests centered in the Middle East, Getty stayed abroad and never returned to California after 1951. (He settled permanently in England, at an estate named Sutton Place, in 1959.) As he refused to fly—the result of enduring a harrowing flight from St. Louis to Tulsa in 1942—he was deterred from returning because of the length of time it took to travel from Europe to California by ship and rail.

As for the Getty Center, Getty was not directly involved in its establishment. Following his death, his will revealed that he’d left the bulk of his fortune to the J. Paul Getty Museum Trust, which had the broad mission to support “the diffusion of artistic and general knowledge.” The board of trustees and museum staff then faced the challenge of figuring out how to use the museum’s enormous endowment to serve that mission. Research and discussion with experts throughout the international art world helped them chart a direction for the renamed J. Paul Getty Trust, which created programs for supporting art exhibition, conservation, research, and education, and built the Getty Center in Brentwood.

Little-known fact: Before Getty commissioned a villa for his property in Malibu, he bought a couple in Italy: La Posta Vecchia at Palo, Ladispoli, and a villa on the island of Gaiola, just off the coast of Naples. In the process of rebuilding La Posta Vecchia, which was in ruins when Getty purchased it, ancient Roman ruins were found and Getty had a small museum built on-site to showcase them. Today the villa is a luxury hotel; the museum is open to registered guests and visitors by appointment.

Currently, you can see nearly a third—about 100 objects—of J. Paul Getty’s personal collection across the Getty Center and the Getty Villa.

Getty collected in specific areas of art, limiting his acquisitions to schools “that [he] liked best and interested [him] most,” and that satisfied his desire to “own a few choice pieces [rather] than amass an agglomeration of second-rate items.” These areas were: “Greek and Roman marbles and bronzes; Renaissance paintings; sixteenth-century Persian carpets; Savonnerie carpets and eighteenth-century French furniture and tapestries.”

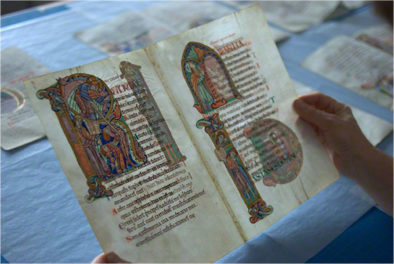

The Getty Museum’s collection has since expanded to also include manuscripts, drawings, and photography. And the newer Getty Research Institute, founded in 1985, collects in a vast variety of areas including historic archives, artists’ books and letters, prints, rare books, and photographs. But Getty’s personal influence on the collection is still apparent in our galleries. Next time you’re at the Getty Center, check out a mobile tour that highlights 11 artworks from each of Getty’s favored collecting areas that he acquired during his life.

Getty really did have a payphone installed at Sutton Place, his home outside London—but not exactly for the reason you might think.

Getty is notorious for being cheap, likely largely because of this anecdote. In his autobiography, he recounts the story behind “the World’s Most Famous Coin-Box Telephone,” and offers the reason for it was fiscal responsibility rather than miserliness. (You can find Getty’s account on pages 316–318 of As I See It.)

Getty explains that he did not own Sutton Place; it was the property of Getty Oil and its stakeholders. The payphone was installed during the period of renovation of the mansion, after the estate manager discovered soaring telephone bills that appeared to be the result of long-distance and overseas calls made by the many people passing through the premises. A payphone was installed in “a smallish, but easily accessible, room on the ground floor of the house,” and—what is more—“special dial-locking devices were placed on each of the half-dozen or more regular telephone instruments located in various parts of the house.” The locks and payphone were removed after about 18 months.

Want to learn more?

- For the details on Getty’s life in his own words, check out his autobiography: As I See It.

- For a sample of Getty’s thoughts on art, see The Joys of Collecting.

- Want to know more about the development of the Getty Center or Villa? Take a look into our Institutional Archives, and see Inside the Getty and the Guide to the Getty Villa.

i love getty museums and his collections

Thank you very informative learned many facts about this wonderul man.when ever I visit Losangeles always visit the Getty museum, there is always a new exibition to enjoy..

Best regards from Istanbul

Inci Tunay MA

Thanks for reading–and for visiting the museum!

I lived in Los Angeles for 13 years and my favorite places to go was Getty Center and Villa. I worked as a delivery driver in a Pizzaria in Malibu, and I used to delivery lunch in the Getty Villa to the employers in the construction field. Amazing experience! I’m in Brazil.

My father worked as a contractor for Getty Oil in Mina Sauid in Kuwait on the Gulf. His son visited and had dinner at our trailer. We all lived in trailers on that project. My mom walked in on him when he was on the throne. The restroom being in the center of the trailer and my mom was in the back bedroom when they arrived and did not know he was there. My father and I had dinner with J. Paul at Sutton Place on our way back to the States as he wanted to hire my father. I remember the pay phone and eating at a huge table. When we got out of the car they told us not to come out alone. There were huge Alsacian dogs (sp.) that weighed about 150 pounds that would attack. My father suggested Getty developed lateral drilling. The rigs may have been in Kuwait but he was drilling in Saudi.