Sir Denis Mahon (1910–2011) is undoubtedly one of the greatest art historian-collectors of the twentieth century. He was a key figure who, starting in the 1930s, brought Italian Baroque painters back to the attention of English-speaking audiences, reversing the critical aversion to seicento art that had prevailed since the previous century.

Born in London into a wealthy Anglo-Irish family, Mahon attended Eton College and then went up to Christ Church, Oxford University, where he received a degree in history. It was then that he conceived an interest in art history. Since the discipline was not at the time offered in British universities, he decided to stay in Oxford for a post-graduate year working under the supervision of Kenneth Clark, who was then keeper of Western art and director of the Ashmolean Museum (and would later direct the National Gallery).

It was Clark who suggested to Mahon he concentrate on the Italian seicento, a field that was both under-studied and underappreciated thanks to the influence of art critics like John Ruskin and Walter Pater, who had been champions of the Renaissance. Ruskin once wrote: “the sixteenth century closed, like a grave, over the great art of the world. There is no entirely sincere or great art in the seventeenth century.” In 1937 Mahon wrote his first article devoted to Guercino, noting that seventeenth-century painting was the “neglected Cinderella of Italian art.”

After coming down from Oxford to London in 1933, Mahon was attracted to two newly founded institutions that were part of the University of London: the Courtauld Institute, founded in 1931, and the Warburg Institute, which had moved from Hamburg to London in 1933. This was an institution comprising both a great library and a staff of dedicated scholars trained in the humanities, of which art history had been an important part in Germany. It was at the Warburg that Mahon met two German specialists in the Italian baroque, Rudolf Wittkower, who focused particularly on architecture and sculpture, and Otto Kurz, who had recently written his dissertation on Guido Reni, and whose professional life for the next twenty years was to be closely connected with Mahon’s.

Mahon also started to attend the lectures on seicento painting given at the Courtauld by Nikolaus Pevsner, another scholar recently arrived in London from central Europe. Pevsner suggested to Mahon the research topic that would become his lifelong interest. Besides Kurz’s dissertation on Reni, important work had already been done or was in progress on the Continent on Caravaggio by Roberto Longhi, on Annibale Carracci by Hans Tietze, on Ludovico Carracci by Heinrich Bodmer, and on Pietro da Cortona by Hans Posse. “Why not Guercino?” said Pevsner.

The power, superb technical ability, bold composition, and psychological intensity of Guercino’s paintings immediately attracted Mahon. After doing the preliminary reading on his subject—especially the important “Life of Guercino” published in 1678 as part of the Felsina Pittrice by Count Carlo Cesare Malvasia—Mahon set off in 1935 with his friend Kurz to tour Britain and Continental Europe in search of Guercino‘s paintings and drawings. He traveled as far as Russia but especially concentrated on Cento, Ferrara, and Bologna, where Guercino had been most active.

Jacob Blessing the Sons of Joseph, c. 1620, Guercino. On loan from the National Gallery of Ireland

The previous year, not long after starting his study of Guercino, Mahon bought in Paris his first painting by the artist, Jacob Blessing the Sons of Joseph. At the end of his long life, he bequeathed it to the National Gallery of Ireland, which has loaned the painting to the Getty Museum for comprehensive conservation treatment and study until later this year.

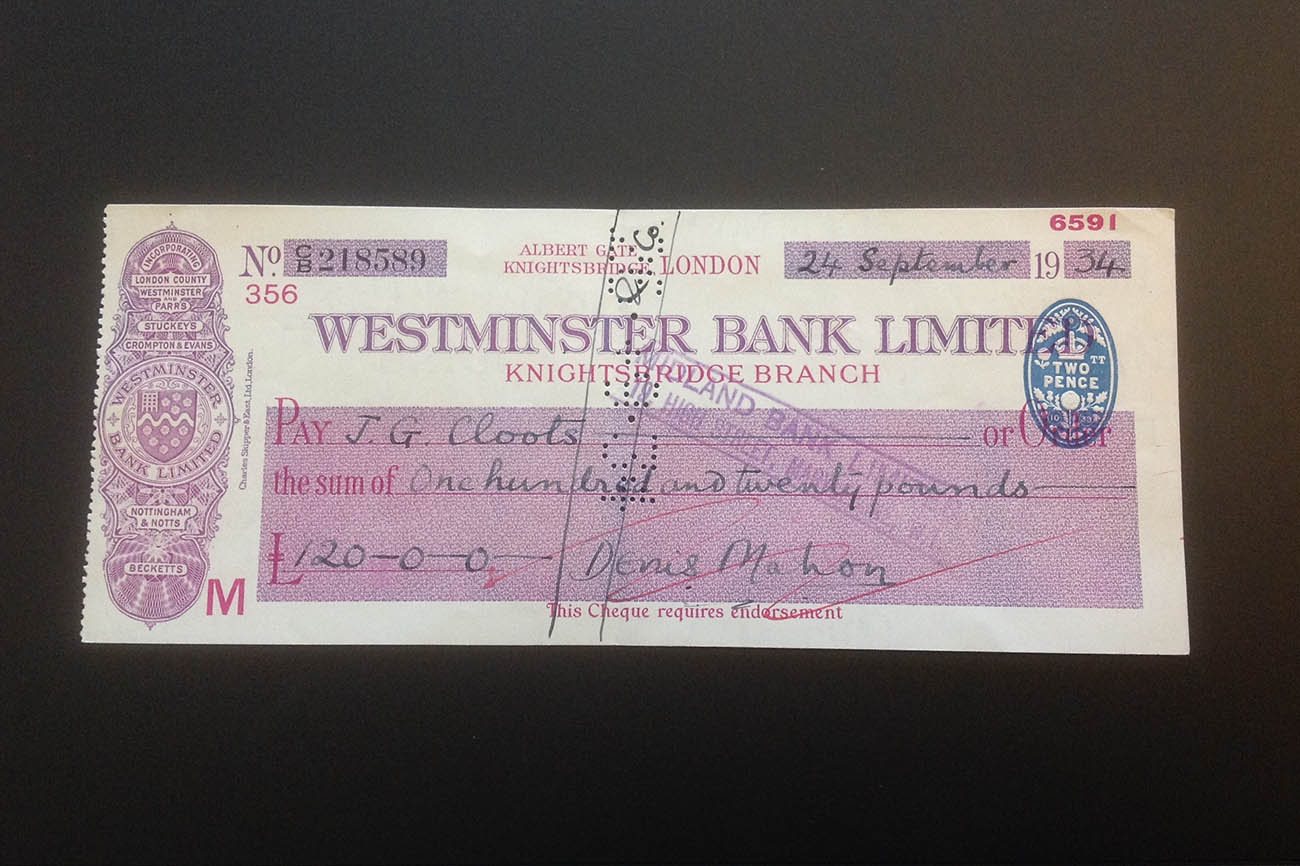

Denis Mahon’s original check purchasing Jacob Blessing the Sons of Joseph from the Galerie Alice Manteau in Paris, 1934. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Ireland, Sir Denis Mahon Archive & Library Collection

Among the Mahon papers today preserved at the National Gallery of Ireland there is still copy of the check for £120 that he wrote for the painting in September 1934 to the Galerie Alice Manteau, located at 14 Rue de l’Abbaye, Paris. In the following years Mahon, who was always dedicated to solid documentary evidence, wrote several times to the dealer asking for more information about the provenance of the painting. He was ultimately able to trace the provenance of the picture almost without interruption, from the time of its execution around 1620 until the sale of the collection of Lord Northwick in 1859—though a gap in ownership records still remains from 1859 until the reappearance of the canvas in Paris in 1930.

Mahon’s handwritten record of the ownership of Jacob Blessing since its creation about 1620. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Ireland, Sir Denis Mahon Archive & Library Collection

On November 2, 1934, Kenneth Clark wrote this message to Mahon, his former pupil: “You are certainly to be congratulated on having bought it. I imagine that in time to come Guercino will be rated a great deal higher than Piazzetta [an eighteenth-century Venetian painter] and his rare early work will be very valuable.” He was indeed right, largely thanks to Mahon’s devoting much of his life to rehabilitating the reputation of Guercino. Today the master’s early works are unanimously considered among the pinnacles of the Italian baroque, and they are also extremely rare and valuable on the market.

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.