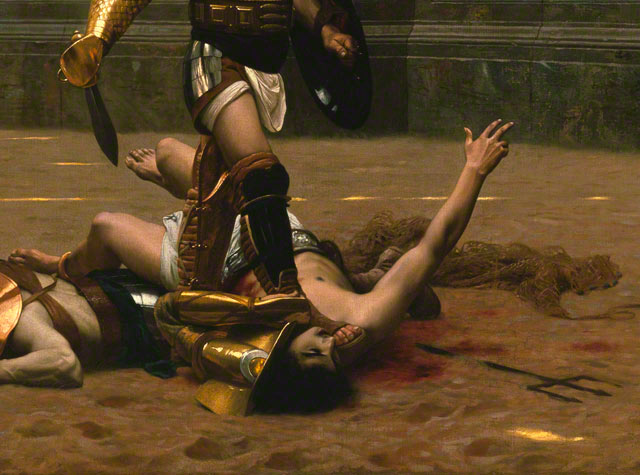

Pollice Verso (Thumbs Down), Jean-Léon Gérôme, 1872. Phoenix Art Museum. Museum purchase. Photograph by Craig Smith

Visitors are captivated by The Spectacular Art of Jean-Léon Gérôme. I met a couple from Miami who were so intrigued by a review of the exhibition in The Art Newspaper that they decided to fly to L.A. to see it. They quipped that the trip was far cheaper than flying to Paris, the second venue of this talk-of-the-town show.

Gérôme’s works excite and provoke audiences as much today as they did in the second half of the 1800s. This certainly makes for a fascinating exchange on the exhibition tour, which I lead at 1:30 p.m. every day—as it no doubt will at our three-part gallery course on Gérôme starting next Saturday, August 14.

My experience as a gallery teacher has taught me to appreciate the active role the public plays in gallery tours. Purposely or not, the group frames the content and delivery of what I do. At the outset of the tour, most visitors say they have never heard of Gérôme; by the end, they all, inevitably, discover how deeply this artist’s images resonate with them.

A case in point is the poster child for the exhibition: Pollice Verso, an image of gladiatorial combat that’s the focal point of the “Thematization of the Spectacle” section of the show. The phrase pollice verso is ambiguous; it’s Latin for “with a turned thumb.”

One afternoon, a discussion arose about whether the thumb was “turned up” or “turned down” to indicate that the defeated gladiator should be condemned. There’s considerable debate about what the gesture actually did mean. A classical source suggests that the default action was to kill the defeated opponent; thus, “thumbs down” would have signified that the losing gladiator was to be spared, and “thumbs up” meant he was to be killed.

So, in Roman times, Gérôme’s recumbent retiarius, depicted with his attributes of the trident and weighted net, would have survived his grueling death. However, thanks to the power of Gérôme’s image, that single, powerful moment of “thumbs down” came to be understood to mean no reprieve for that fallen foe, and thus arose the popular interpretation of finishing off the victim.

Is it any wonder that the public, as well as cinematographers, are taken in by Gérôme’s commanding depictions, as he chooses offbeat moments to illustrate the narrative of his works? We see the gladiator from behind, which entices us even more to piece together the various frames of the story. As a result of modern cinema, we can better understand the immersive technique of Gérôme, a compelling figure highly criticized in his own day. The painting is said to have been the catalyst for Ridley Scott’s film Gladiator, and currently there is a new mini-series based on the same theme: Spartacus: Blood and Sand.

Pollice Verso is one of Gérôme’s most famous canvases; it engages our imagination and curiosity. Were the gladiators slaves or special soldiers? Would it have been a punishment or a privilege to be one? People are curious about who these larger-than-life characters actually were.

Inevitably, someone will ask about the animated characters at the right. Who is that group of women dressed in white veils? Everyone gets quite a kick out of the answer: the vestal virgins. Those revered priestesses were responsible for tending the sacred flame of the House of Vesta on the Forum. The artist satirizes the group as bloodthirsty cheerleaders in ringside A-lister seats, their reserved place of honor at public games and performances. Such behavior belies their divine status and sacrosanct life of privilege.

Gérôme wasn’t the first artist to inspire film. Yet his unique cinematic imagination and consummate artistic skill engage us as spectators, and we play an active role in viewing his works.

This retrospective, the first in 40 years, offers something for everyone. It’s a dazzling spectacle, and the summer crowds are as enthralled by it as were those rowdy vestals at the Colosseum.

This well-written and descriptive blog entry really gives insight into what it might be like to participate in one of Christine’s tours–namely, completely fun and fascinating!

Christine’s eloquently written blog provides even more life to a painting that is very much alive. Her insights and explanations receive a very positive “thumbs up” 😉

Great article and cool photos!

Do you know where this painting is now?

The canvas is at Musee d’Orsay, in Paris.

What a derivative, assumptive and historically errant post. She needs to forego perusing the assigned “tour guides script” and read a book. The items she speculates upon are cleared by original sources. Thumbs down manifestly assigns death. As well, Gerome himself responded in a very strident manner to the idea that he ever conveyed satire. He took offense to painters using satire and called in juvenile – best left to thespians. This is a sad example of post-modern ignorance of subject