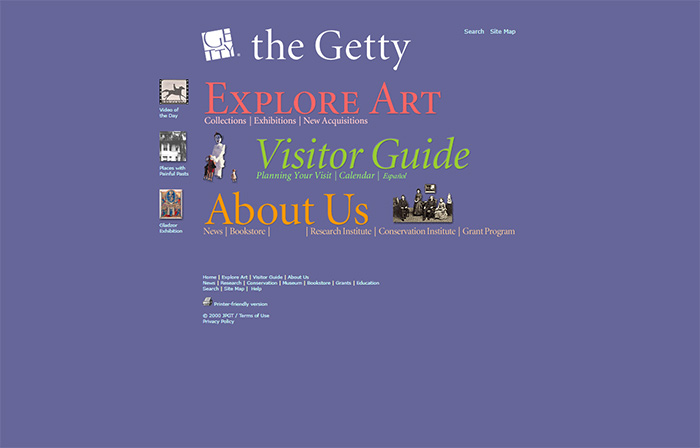

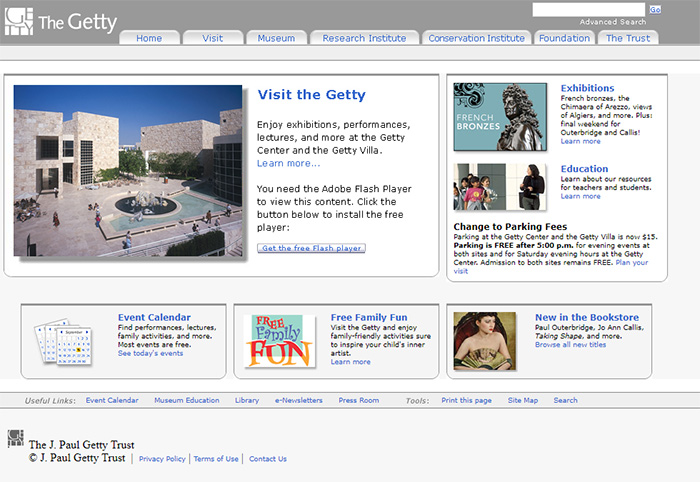

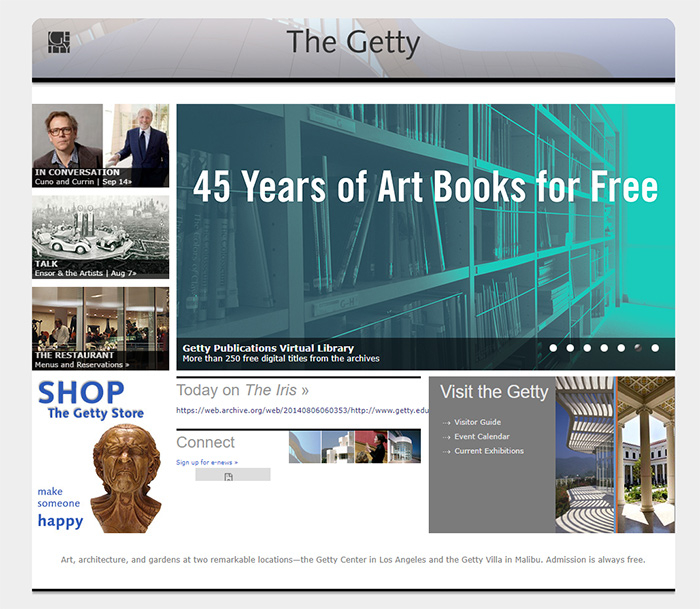

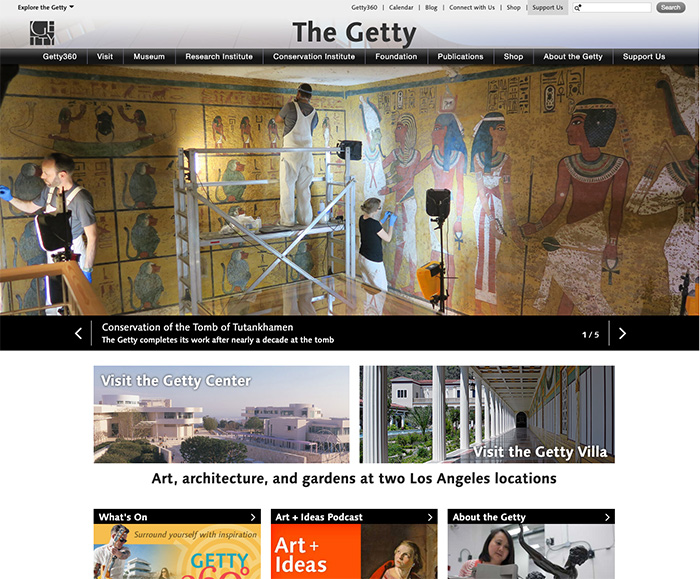

Today’s World Digital Preservation Day is a good time to think about at-risk digital materials. People often forget that websites are included in this category, but just in the last decade the online landscape has changed drastically. No longer do we see sites like MySpace, Friendster, or GeoCities. We are no longer bombarded with pop-ups, Flash content, or neon colors. Yet this begs the question: why do we preserve this content that changes so quickly?

At Getty, we have been preserving our physical institutional materials, such as brochures for public programming and paper administrative records, for decades. Preserving the digital information we produce, like our website, is just as important for recording our institutional history.

“The Getty website is our most important and informative tool for communicating and engaging with a wide variety of people,” said Nancy Enneking, head of Institutional Records and Archives. “It documents the way Getty evolved over time.”

We recently ran into some of the challenges of preserving at-risk materials when trying to preserve a project that started in 2008, the “Rembrandt in Southern California” section of Getty.edu.

Trial and Error: The Challenges of Archiving an Old Website

Screen captures of the previous Rembrandt in Southern California site (left) and the current redesigned version (right).

The impetus for archiving the Rembrandt site came from Betsy Werner Brand, a content production specialist at the Getty Museum. She requested we archive the original Rembrandt site section in preparation for a redesign.

Werner Brand explained that she wanted the previous design preserved because, “as a content producer, I’m looking at how our site functions currently and in the future, but also to learn from how we did things in the past [to] make our website function for as long as possible without becoming dated.” She also wanted the old site to be accessible, while ensuring that only the redesigned site would be indexed by Google.

Unfortunately, the site was fraught with issues: pop-ups, Adobe Flash, Google Maps, and an unknown media player.

Flash is especially problematic as support ends in December 2020, making it likely that Flash content will not be accessible at all in the near future. In fact, the newly released Bitlist classifies websites with Flash as critically endangered.

Screen captures of the previous Rembrandt virtual exhibition (left) and the audio page where you can download the full audio files (right).

Through trial and error, all of these components were archived to varying degrees of success. On the left side of the homepage, there is a missing Flash component that we were unable to capture through our web archiving software, Archive-It. We were also unable to properly capture audio files embedded throughout the site, as they only work intermittently. However, both the Flash content and the audio files were accessible through alternative methods. The Flash slideshow could be accessed by clicking into the virtual exhibition, and the audio files could be downloaded directly into a ZIP file.

Error message from Archive-It that Google Map pop-ups were not captured.

In contrast, the “visiting information” section of the website had many Google Map pop-ups to the other participating museums—but they were not preserved at all.

With these discoveries, we went back to Werner Brand to determine whether or not the missing content was vital. For the Flash and audio components, our capture was acceptable because the content is still accessible. The Google Maps were also considered a low priority because the addresses are publicly available and are not integral to the Rembrandt site.

Therefore, while we are unable to provide an exact replica of the old website with full functionality, we were still able to preserve an archived version that is sufficient for future reference. If more time and resources were available, it is possible that the archived site would be more complete. But this is an issue we constantly contend with in web archiving. How much can we realistically preserve?

Getty’s Future in Web Archiving

Web archiving can be time-consuming and complex. Additionally, the conversation about digital preservation of web content is continually evolving. Who ultimately decides what content needs to be captured? How much time and effort is reasonable to put into the preservation of digital materials like websites?

Regardless of these challenges, web archiving is necessary work that contributes to an increasingly important resource for Getty and the broader community.

Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine capture timeline for getty.edu as of October 16, 2019

There is a wide variety of individuals and institutions interested in ensuring that Getty’s digital presence is preserved. A search for “getty.edu” on the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine shows that in the past two decades there were over 4,700 captures of the Getty’s website. The Getty’s formal web archiving initiatives didn’t begin until 2016, but other institutions and individuals have captured the website all the way back to 1998.

Moving forward, we aim to further enrich our web archiving program. “We’re delighted to be finally proactively capturing our public presence more comprehensively,” Nancy said. Capturing this content is the first step in ensuring access for future researchers.

Comments on this post are now closed.