A giant of the British art market: Portrait of James Christie, 1778, Thomas Gainsborough. Oil on canvas, 49 5/8 x 40 1/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 70.PA.16. Gift of J. Paul Getty

The Getty Provenance Index has, for three decades, been a leading resource for scholarship on the history of collecting. Founded in the early 1980s by Burton Fredericksen, the first curator of paintings for the Getty Museum, the Provenance Index has evolved into a collection of online databases with 1.5 million records indexing the works of art described in source documents such as auction catalogs, archival inventories, and dealer stock books. This data can be used to trace the ownership of works of art, and also to examine patterns in collecting and art markets.

A recent project added almost 100,000 database records for the contents of British sales from the years 1780 to 1800. These records make it possible to search for paintings, drawings, sculptures, and miniatures that appear in over 1,200 British sales catalogs from the period.

This recent project, British Sales 1780–1800: The Rise of the London Art Market, was a collaboration between the Getty Research Institute’s Project for the Study of Collecting and Provenance (PSCP) and the National Gallery, London, where a related conference is taking place this week. As a member of the team who worked on this project, I’d like to share the steps involved behind the scenes, from outset to completion.

A Word on the Origins of the British Art Market

The execution of King Charles I in 1649 helped launch the British art market. After the temporary dissolution of the monarchy, the royal collection, which rivaled the best in Europe, was sold off during the 1650s. Thousands of important artworks suddenly went into circulation and the public got its first taste of collecting. While most of these objects made their way back into the royal collection after the Restoration, in 1660, the taste for collecting continued to grow during the second half of the 17th century. The first public art auctions in London took place in the 1670s, but the earliest surviving catalog dates to 1682, for a posthumous sale of the collection of the painter Sir Peter Lely. Don’t worry; Sir Peter died of natural causes and there was no decapitation involved.

The recent project picks up the story a century after that Peter Lely sale. By the 1780s, the British art market was in full swing, and many of the major auction houses we know today, such as Christie’s and Sotheby’s, had already been established. This period saw a significant increase in art sales. The French debt crisis and subsequent revolution resulted in a dramatic redistribution of art in Europe, with many objects, in some cases entire collections, leaving the continent for sale on the London art market.

One interesting example of this is the collection of Charles-Alexandre de Calonne (1734–1802), finance minister under Louis XVI, who was forced from office in 1787. After going into exile in England, his art collection was subsequently sold in Paris, but part of the collection was purchased by his mistress, the widow of the French financier Joseph Micault d’Harvelay. Mrs. Anne Rose Micault d’Harvelay (1739–1813) then joined Calonne in England, where she married him and reunited him with a significant portion of his collection. A happy ending to the story, right? Well, not quite. Calonne used the collection as collateral for a loan to fund a futile attempt to restore the French monarchy. After he defaulted on the loan, his creditors sold his collection in London in 1795, bringing him the strange distinction of losing the same collection of pictures twice. Mr. and Mrs. Calonne eventually returned to France…where they died in poverty. I know it’s sad, but maybe this will cheer you up: one of the pictures from that 1795 sale, Gerard ter Borch’s Lady Instructed by her Music Master, is now at the Getty Museum.

The Music Lesson, about 1668, Gerard Ter Borch. Oil on canvas, 26 5/8 x 21 5/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 97.PA.47

Record for the 1795 auction of ter Borch’s Music Lesson. The record contains the description of the painting from the 1795 sales catalog, which notes, among other salient features, “the choice of this artist’s subjects are in general much more elevated than many of his countrymen, his works are in great estimation for taste and correctness.”

As you can see, art, history, and economics are all deeply intertwined. Providing access to the contents of British art sales from 1780 to 1800 will foster our understanding of this important period.

Here, in brief, is how we did it.

Step One: Collecting the Catalogs

The first step in the process of adding this sales data was to track down the extant copies of the sales catalogs for the period. Our starting point was the inventory created in the early 20th century by Fritz Lugt. The Lugt inventory is available through the subscription database Art Sales Catalogues Online and includes location information and digitized copies for many of the catalogs. Our collaborators at the National Gallery in London were able to obtain copies of nearly all the relevant catalogs in this inventory. But they didn’t stop there. They checked the collections of about 150 libraries and archives, traveling across the UK and also obtaining copies from institutions in the U.S., France, the Netherlands, and other countries. The British art market in the late 18th century was heavily concentrated in London, but our collaborators were also able to find sales catalogs from secondary markets, such as Bath and Edinburgh, as well as estate sales that took place across the countryside.

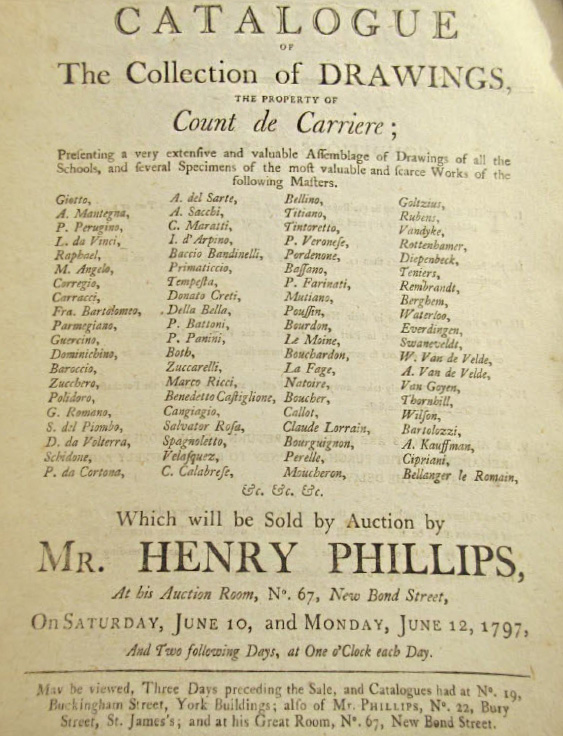

After each catalog was located and copied, a catalog description record was created. The catalog description record is similar to a library catalog record, describing the item at the document level. The following example shows our catalog description record and an image for the title page for a sale of the collection of the “Count de Carriere.” (I believe this was the name being used during exile in London by Etienne Bourgevin Vialart, comte de Saint-Morys, the son of an important French drawings collector.)

“Presenting a very extensive and valuable assemblage of drawings of all the schools…”: Getty Provenance Index record for the 1797 London sale of an Old Master drawings collection.

Title page of the 1797 auction of the drawings collection of the “Count de Carriere,” likely a pseudonym for exiled French count Etienne Bourgevin Vialart.

Step Two: Indexing the Catalogs’ Contents

Our collaborators in London then indexed the contents of the catalogs. The catalog description record links to individual content records for each painting, drawing, sculpture, and miniature that appears in the sale. The user can search for a sale (by date, location, auction house, seller, etc.) and then view all the content records for that sale; or the user can search for individual object records (by artist, title, object type, owner, etc.). Adding these content records was the most time-consuming part of the process. The average sale contained about one hundred lots, but the catalogs we included in this project range from sales of household goods, which might only include a few art objects, to sales of drawings, which could include over a thousand lots.

In addition to being time consuming, adding the content information from these catalogs was much more than simple data entry. The quality of the records was dependent on our collaborators’ knowledge of art history and experience with the organization of the catalogs. Some catalogs were fairly straightforward, while others needed a bit of decoding. For example, a single lot could have two artists in an artist column and then list two paintings in the title column. We had to determine which artist was responsible for each painting or decide that the artists were actually working together.

Other information was added to the database records, including the object type, format, materials used, and any signature or mark that might appear on the object. For this recent project we also added subject categories, making it easier to restrict a search to a specific type of painting, such as a landscape or a history painting. While the subjects are very basic, they do provide some assistance when the exact title isn’t known. For instance, “marine,” “seascape,” “sea-piece,” “shipping,” “strong gale,” etc. can all be searched together by using the subject term “marines.”

Step Three: Transcribing the Annotations

The most challenging part of the process was the interpretation of the hand-written annotations found in the various copies of the catalogs.

These annotations fall into three main categories. First, there are extra lots added by hand after the catalog was printed, or handwritten changes to the printed titles or artist names. Second, there are notes, often written by another dealer who attended the sale, commenting on the quality, authenticity, or previous ownership of an object. Third, and most important, there is transaction information. When possible, we have indicated if a lot was sold, for how much, and who the seller and buyer were. Approximately two thirds of the content records have price information, and almost 80% have buyer or seller information (some of the seller names came from annotations and others came from the title pages of the catalogs).

We used the annotations from the auctioneer’s copy of the catalog, when available. This is usually the most complete and accurate transaction information. Most auctioneer’s copies include interleaved pages marked off in columns, with the seller at the left margin, followed by the lot number, one or two price columns, and then the buyer’s name, if there was one. The following example is an auctioneer’s copy for a 1798 Phillips sale.

Auctioneer’s copies are often rich with annotations about art sales. Here, a spread from a 1798 London art auction, with copious hand-written notes on the recto.

Why are there two price columns? Good question. I’m glad you asked. One column is for the sale price and the other is for something called the “buying in” price, which I’ll explain in a moment. The first price column usually represents the actual sale price of the lot. If there is a price in this column, and different names in the buyer’s and seller’s columns, then all is well with the world and we can safely assume the lot sold. If the first price column is empty and the price is in the second column, we consider this the “bought in” price. The term “bought in” (sometimes written as “bot in”) was usually used when the bidding didn’t reach the reserve price and the highest bid was recorded but the lot was not sold. In these cases there is sometimes a name in the buyer’s column, but it is probably the name of the seller, or the name of the highest bidder prior to the lot being bought in, or even a name the auctioneer was using as a “buying in” name (this could be a real person or a fake name). These cases were also fairly straightforward, and we recorded the lot as “Bought In,” which essentially just means the lot didn’t sell. But the bought-in price still provides some idea of the value of the object. If the buying-in price is low, we know there was nobody at the sale who was willing to bid very much for the object. If the buying-in price is high, we know the seller had a high reserve price on the object.

Other possible transactions are “Passed” or “Withdrawn.” If there is no price or buyer in the relevant columns, this indicates that nobody bid on the object. Passed lots were usually marked as such (often spelled “past”), and withdrawn lots were usually crossed through. Both terms essentially mean that nobody bid on the object and that it was, therefore, not sold. The distinction is this: a withdrawn lot was pulled prior to the start of bidding, while a passed lot was put up to bid but received no interest. However, this distinction isn’t very meaningful, because we generally don’t know if a withdrawn lot was pulled several days before the sale due to a change of plans, or if it was pulled just moments before the bidding was supposed to begin because the auctioneer read the room and decided it was hopeless.

If we weren’t able to obtain the auctioneer’s copy, we were sometimes able to get a copy that had transcriptions from someone who attended the sale, often another dealer. While these copies are usually less complete and accurate than the auctioneer’s copies, they still provide useful information. A person who attended the sale was sometimes able to record the hammer price and the name of the buyer. In cases where we have no annotations at all we recorded the transaction as simply “Unknown.”

Step Four: Editing

After the contents of the catalogs were indexed by our London collaborators, photocopies of the catalogs were sent here to the Getty Research Institute, where they were added to the PSCP’s Sales Catalogs Files. These files include photocopies of most of the sales catalogs that appear in the Provenance Index databases. These are distinct from the auction catalogs in the Getty Research Library’s collection and must be searched separately. We maintain these photocopies both for purposes of departmental editing and for consultation by scholars. It is always a good idea to look at an actual copy of a catalog once an object has been identified in our databases. While we have made every attempt to accurately represent the information, it’s impossible to convey all the subtle implications of formatting and organization that appear in the physical catalogs. It may also be necessary for researchers to confirm our transcription of the handwritten annotations.

During the editing process, we enhanced the data to improve searching in several ways. The most significant was by providing authority control for artist and owner names. Authority control means we have provided preferred “authority” forms of the names appearing in the catalogs, creating consistency in the main access points for the records.

Providing authority control for artist names does not mean we have verified the attribution or guarantee that a particular artist created a work. Instead, it is an attempt to group together various spellings, misspellings, and different forms of an artist’s name so that the records can be found in a single search. Without the authority control, trying to find all the paintings by Brueghel, for example, would require searching for “Brueghel,” “Breughel,” “Brugel,” Breugel,” “Brugle,” and dozens of other variations. But with the addition of the “authority” form of the name, searching for “Brueghel” will return results for any of those alternate spellings. In cases where the artist could be one of several family members, we used a generic family name. However, in cases where it is very likely to be a specific family member, we included the individual artist’s name. In other words, we added the name of the artist we think was most likely being referred to in the catalog. The name as it appears verbatim in the catalog was also included in the record, so a user can check the name and possibly come to a different conclusion.

We also provide authority control for the names of many of the buyers and sellers who appear in the catalogs. This was even more challenging than for the artists. One reason for this is that the artists’ names printed in the catalogs were intended to be recognized by all the potential buyers at a sale, whereas the names of buyers and sellers were usually noted for the auctioneer’s own records. The auctioneer needed to know who to send the bill to; he probably wasn’t considering that hundreds of years later we might wonder who he meant. The other thing that made the buyer and seller names so challenging was that they were usually recorded by hand and were often very difficult to read. Many of the names were also written as abbreviations. We had to study the handwriting of the different auctioneers and dealers who added the annotations to the catalogs.

Despite these challenges, we were able to provide an “authority” form for the names of many of the buyers and sellers appearing in these catalogs—several of whom were important dealers and collectors during this period. Again, we can’t guarantee that the name we have provided was the actual person buying or selling; we can only provide the best candidate based on the information we have. In the database records, we included our transcription of the name as it appears verbatim in the catalog. It is the responsibility of the user to check this name and, when possible, the original catalog, and draw his or her own conclusions.

In the following example, the annotations in a 1782 Christie’s sale show that lot 75 was sold by “VDG” to “Daigmt” for £5.2. The PSCP staff has determined that “VDG” refers to Benjamin van der Gucht and “Daigmt” refers to Paul d’Aigremont, and these “authority” names have been added to the database record to improve searching.

Detail of annotations from a 1782 Christie’s sale showing lot 75, sold for £5.2 to “Daigmt” (abbreviation for Paul d’Aigremont).

Database record for the 1782 Christie’s sale of Jan Baptist Weenix’s “small landscape and figures” by Benjamin van der Gucht to Paul d’Aigremont.

Step Five: Publishing the Data Online

The final step was to make these records publicly searchable online as part of the Provenance Index databases, which occurred earlier this year. These late 18th-century sales can now be searched alongside previously indexed British sales from the early 19th century, in addition to sales that took place in France, Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands. We hope these new records will lead to a better understanding of the art market during this crucial period.

As a PhD research student I am keen to assess the popularity of William Hogarth’s prints 1732-1764, (the main part of his career.) I refer to his ‘moral cycles’ such as The Harlot’s progress/The Rakes Progress/Marriage-a-la-Mode etc.The benefit of auction sales catalogues is that they demnstrate the extent of Hogarth’s popularity once the prints had left his own hands and show his worth on the open market. I have conducted limited research at the British Museum but wondered if your research conclusions might help me paint (pardon the pun) a more comprehensive picture of Hogarth and his contemporary popularity. Once I have details of purchasers (and/or price) I can carry out a search on the buyer to determine social status.

Hope you can help.

Thank You

Mark Mcnally

Thanks for your interest in our project, Mark.

Unfortunately, while the Provenance Index could provide information about the market for Hogarth’s paintings from 1780 to around 1840, we haven’t recorded the sale of prints and we also do not currently have many British sales from earlier in the 18th century (though we plan to add these in the future). Fortunately, there were fewer sales earlier in the 18th century, which means it might be possible to go through them all by hand. I checked the database Art Sales Catalogues Online and found 122 London sales with prints for the years 1732-1764. Some are available online and others should be available at the British Museum, etc.

Good luck with your research.

Eric Hormell

Is it possible to access the Art Catalogues online? I have accessed it at the British Library and the V&A but I need to get further information and travelling to London each time to check on something is not viable. I have an auction label on the back of the painting I am researching. Is there a database of auction house labels? Mine says 1214 CR + V.