An Indian Man, about 1878–79, Georges Seurat. Graphite, 19 1/16 x 11 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2014.11

Of all the artworks I’ve researched and written about this year as a graduate intern in the Drawings Department, none is as stunning and perplexing as our recently acquired drawing An Indian Man by Georges Seurat.

The name “Georges Seurat” immediately suggests visions of multicolored dots of paint arranged to create forms through light and color. Seurat’s so-called “pointillistic” paintings are mesmerizing and dizzying to the eye, and it is what he is most known for today.

Seurat was, however, also a prolific and extraordinarily original draftsman, as evidenced by other works in the Getty’s collection. Madame Seurat, the Artist’s Mother demonstrates how Seurat used black Conté crayon and the rough texture of paper to create nearly imperceptible tonal gradients that build form. He made Madame Seurat around 1882–83 at the height of his career.

Madame Seurat, the Artist’s Mother, about 1882–83, Georges Seurat. Conté crayon on Michallet paper, 12 x 9 3/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2002.51

Breaking with Tradition

The addition of An Indian Man to the drawings collection gives a unique glimpse into Seurat’s beginnings as a draftsman and an artist. He made it around 1878–79 as a twenty-year-old art student in Paris.

An Indian Man is very different from Madame Seurat in technique and subject matter. While Madame Seurat is dark and shadowy from the application of Conté crayon on bumpy paper, An Indian Man is shaded in white, powdery charcoal on smooth paper. Yet we can see from this earlier work how Seurat began to develop his technique of building up his drawing medium to form soft gradients. The mature Seurat is known for his depictions of the everyday, so it is surprising that as a young artist he selected a man who would have been so exotic to him as a sitter.

Indeed, this drawing is singular among Seurat’s other drawings made when he was an art student, which depict standard, muscular, young, “ideal” male models used in life-drawing classes. An Indian Man signifies a decisive point in Seurat’s artistic career where he veered away from the traditional and academic in search of the modern and experimental.

Who Is the “Indian Man”?

This drawing is pivotal to understanding Seurat’s later work, but it also poses questions about the young Seurat and his early break from academic standards and rules. For example, who was this model, so entirely outside the bounds of the academic norm? How did Seurat meet such a man in 1878 Paris?

To look for answers, I went to the existing literature on Seurat. Unfortunately, An Indian Man has been little discussed, except to say that it’s a landmark in Seurat’s early work. Even more to my dismay, the identity of the sitter is always described as an “Indian,” “Hindu,” and even “beggar,” with no further explanation. So I turned to other sources from the time that might yield more clues about this mysterious man’s identity.

Detail of Seurat’s An Indian Man showing the finely rendered beard and topknot

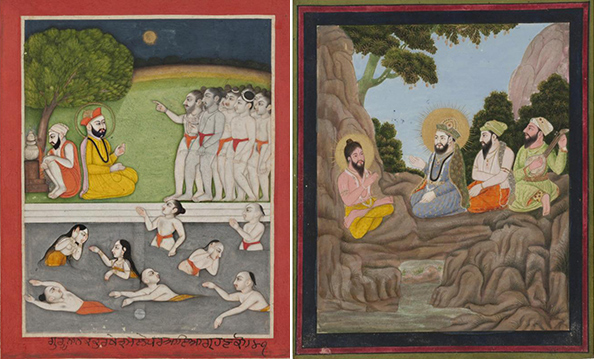

The past titles and descriptions of the drawing in the literature and his physical attributes, especially the beard and top-knot, suggest that the sitter is Indian. I searched books, catalogues, and collections looking for other images of Indian men in the 19th century, which bore parallels to Seurat’s sitter. The Asian Art Museum of San Francisco’s extensive collection of Indian art includes a 19th-century Indian manuscript with some miniatures that seemed helpful:

Miniatures from a manuscript of the Janam Sakhi. Left: Guru Nanak encounters a group of ascetics at Kurukshetra, about 1755󈞲, made in India, probably Murshidabad. Pigments on paper, 8 x 6 3/4 in. Right: Guru Nanak’s meeting with Dhru Bhagat on Mount Kailasa, 1800s, made in Lahore, Pakistan. Opaque watercolors and gold on paper, 8 x 7 in. The Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, 1998.58.37 and 1998.58.27. Gift of the Kapany Collection

These leaves from the Life Stories of Guru Nanak (the Janam Sakhi) show Sikh gurus and Hindu ascetics engaged in different ritual activities such as bathing or meditating. The sitter in An Indian Man shares attributes of both Sikhs and Hindus. Both religions require specific hairstyles for men. Sikhs, as a tenet of their religion known as kes, never cut their hair and beard. In addition, they are required to comb their hair with the kangha, wear it in a top-knot, and cover it in a turban. In addition, the top-knot and beard are sometimes worn by Hindu ascetics, also known as sadhus, who live an austere, monk-like existence. Although we still do not know for sure, these are two viable possibilities for the sitter’s identity.

Where Did Seurat Meet Him?

Interior of the Indian Palace on the Champ-de-Mars, Universal Exposition, Paris, 1889. Engraving after drawing by J. Mirma. Original drawing: Groupe de recherche Achac, Paris

Another question now demanded to be answered: where could Seurat have met such an unusual figure in 1878 Paris?

In 1878, the Universal Exposition was in full swing in Paris. Here people from all around the world gathered to display and see new technologies, arts, and sciences. Researching 19th-century world’s fairs, such as the 1878 Universal Exposition, took me down a dark road of colonial exploitation and imperial domination. It was quite common for colonial peoples, alongside goods and technologies, to be displayed in the pavilions. Some countries went as far as to create human zoos filled with “attractions” such as African Pygmies, Native Americans, and Indian yogis. In the 1878 Universal Exposition, Seurat’s brother-in-law (whose wife, Seurat’s sister, was once the owner of An Indian Man) had a booth dedicated to his glass-making business. Seurat could have encountered his model at the Exposition, given the high concentration of foreign peoples in Paris for the fair.

Given the demeaning treatment of non-Europeans at the Exposition, Seurat’s dignified depiction of an Indian man becomes even more extraordinary. The soft fall of light on the man’s chest, the delicate rendering of his beard and wrinkles, and the use of negative space create a calm, serene atmosphere that celebrates the sitter’s body rather than exoticizing it.

An Indian Man remains a mysterious drawing in Seurat’s body of work. We may never know the true origins and background of the man in the drawing, but it is this very mystery that makes An Indian Man such a mesmerizing object. Come see it for yourself through August 24, 2014, in the Getty Center’s West Pavilion.

If you have ideas about the sitter’s identity or how Seurat might have encountered him, we would love to hear from you.

Comments on this post are now closed.