On a Sunday, you might find artist Betye Saar at the Pasadena College flea market, scouting for treasures. The energetic 85-year-old is still an active hunter of offbeat and unusual objects, which she combines into sculptures filled with personal, spiritual, and political power. Saar sat down with us in the green room before she appeared at our panel discussion on assemblage to look back on the Pacific Standard Time era and reveal the alchemy of her process.

Have you been visiting some of the Pacific Standard Time shows that feature your work?

I went to MOCA while they were installing their exhibition, and of, course, the Hammer, three or four times.

At the Natural History Museum there’s a small display in the old rotunda. It’s the museum that was in Los Angeles before LACMA was constructed, and of course MOCA and the Getty. I find that the most interesting space because it’s a space I visited as a kid, going to see the dioramas and the exhibitions. We would get on the bus and go the Natural History Museum.

It’s a small, intimate show, and it’s interesting because it has work by artists like Ed Moses and Ed Ruscha when they were just starting out, so you can see how their work has changed and evolved. There are four women in the show, and the rest are men—so that gives you an idea of what the ratio was for women being accepted in a museum or gallery.

Do you feel that you’re different as an artist now than you were in the ‘60s and ‘70s?

No, but I’m pleasantly surprised that the work still looks good to me. It’s still strong work; it set the pattern for what I do now. Especially the work at the Hammer, which starts out with prints. Printmaking was my segue from design into fine arts.

They have some of the early prints, like House of Tarot. At that time I was really interested in nature, family, and metaphysics. This was, you know, the hippie period when magic and mysticism were really important to that culture.

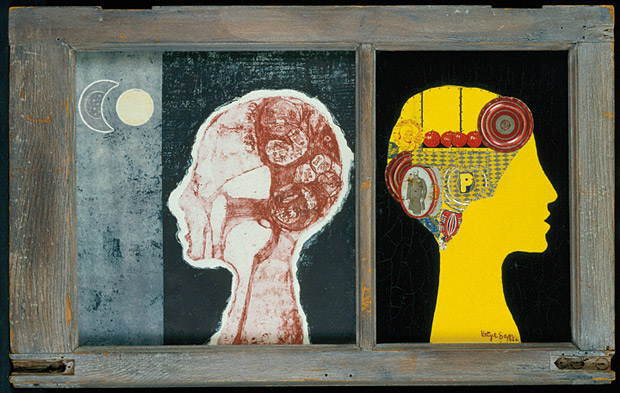

I was beginning to form my visual language, and I used palmistry, phrenology, astrology, the sun, the moon, the hand, the head—things like that.

What got you interested in metaphysics, magic, and the occult?

As a kid I was always interested in fairy tales. My grandmother lived in Watts, and I would see Simon Rodia building the Watts Towers and that was like fairyland, something mystical and strange.

Also, where I lived in Pasadena, they would have gypsy conventions and my dad would drive us there. It was just a big park and all these caravans and things were there. I was always interested in [things that were] outside of the society I knew.

It was very hard to find books on mysticism and magic and witchcraft and all those things, but because it was the ‘60s, those things were just beginning. I found books on alchemy and would incorporate those drawings into my early works.

The Phrenologer’s Window, Betye Saar, 1966. Assemblage of two-panel wood frame with print and collage. 18 1/2 x 29 3/8 x 1 in. Private collection, courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, LLC, New York, NY. © Betye Saar

Are you interested in outsider art?

I’m really, really attracted to outsider art, because that’s what Simon Rodia was: an outsider artist. And that’s what I collect personally.

When I would travel around to give lectures I would ask, “Where are the best thrift stores and where are the best outsider artists?” I would always find really great places where people made yard art, shrine art, or something like that. I was always intrigued by the ordinary becoming special and mystical.

When you go into a thrift store, what objects speak to you and why?

I look for the unusual. I have a very strong intuition. Something says “look in this box,” and you dig through it and maybe you find something and maybe you don’t. When you find it you just know.

I think of my work as being a ritual, and the first part of the ritual is the hunt: finding all the ingredients.

How long do you hold onto the objects you collect?

I can’t always get around to making a piece. I walk around my studio, for example, and see these old-fashioned mantle clocks and [think], “I’m gonna do something about that.” And then on another walk I see that I have little boxes of feet and heads… and then on another walk there’s a table I plan to get to sooner than the others, with glass boxes, because I have this feeling that I want to work with glass and metal but [also] with organic materials like tortoiseshell, plants, gourds, or things like that—combining things that don’t feel good naturally.

You spoke of the first part of your ritual being the hunt. What’s the second part?

The second part is transformation: recycling, combining materials together, altering sometimes. Creating something out of what I found.

The third part would be release: putting it out for exhibition or maybe even a sale. You just put it out there and people like it or they don’t. If it doesn’t feel completed, sometimes it just stays in my studio until I find the right combination.

Do you have an easy time releasing your art?

Things I don’t part with are personal pieces, like things that relate to my family. My great aunt died at 94 in 1974, and she had a trunk full of all the things she brought from Kansas City, Missouri, like old handkerchiefs, gloves, old letters, memorabilia, things like that. So, I just started making art out of all those things, and they’re all really personal.

Two pieces I’ve given away to my grandchildren. My eldest grandson is 22. He’s an art student, and he has Spirit Catcher, which is in the Hammer show, because he’s the eldest; he’s the spirit catcher. My granddaughter, also 22, has another of my pieces.

What guidance would you give to your grandson and other young artists just starting out?

Be as authentic as you can. Don’t let your ego get in the way. Keep trying to learn. There’s an old-fashioned saying that goes “Good, better, best. Never let it rest till your good is better and your better best.” They hate for me to say that! (Laughs.)

Text of this post © J. Paul Getty Trust. All rights reserved.

Comments on this post are now closed.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks