Berlin, circa 1921: The painter Hans Richter turns his talents to film and produces one of the earliest abstract films, Rhythmus 21. Clocking in at just over three minutes, it’s a significant departure from the newsreels, romances, cliff-hangers, and penny-dreadfuls that made up the bulk of film production in the early ’20s—the first decade in which the film industry began to play a major economic and cultural role around the world.

Simple, stark, and short, Rhythmus 21 is a self-conscious meditation on the limits of the medium. It has no figurative representations—neither people nor flowers, and no animals, arrows, or ships at sea. Instead it plays with optical effects of simple shapes: circles, squares, rectangles, lines.

Richter credited his friend Viking Eggeling with the idea of exploring the possibilities for abstract animation. In fact, they’d worked together on a series of paintings on scrolls that preceded both of Richter’s first films, as well as Eggeling’s Symphonie Diagonale (1924).

These films, along with Richter’s Rhythmus 23 (1923), share a visual language, combining black backgrounds with white shapes and lines that seem to grow and change. Yet, Richter’s technique is quite distinct from Eggeling’s. Richter investigates the effects of cut-out squares and rectangles as they appear now in the distance, now in the foreground, while Eggeling’s lines and curves are drawn, un-drawn, redrawn, and moved within a flatter picture plane.

Richter’s and Eggeling’s works also share a common interest in musical and auditory metaphors, but their approaches are distinct: Richter prefers a fundamental rhythm, Eggeling prefers the more refined composition of a symphony. Both emphasize an aesthetic of synesthesia: representing one sense (hearing) within the representational scheme of another (sight).

Their explorations pushed the limits of early film and explored how visual phenomena intersect with concepts traditionally applied to music—rhythm, meter, duration, and tone. For Richter, film, not music, seemed to be the best medium for conveying the art of rhythm.

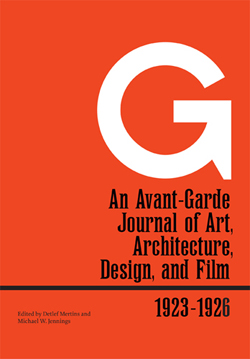

Richter not only conducted his own film experiments, but also eagerly promoted this style and technique, especially in the little magazine he edited, G: Material zur elementaren Gestaltung, recently published in translation by the Getty Research Institute as G: An Avant-Garde Journal of Art, Architecture, Design, and Film, 1923–1926.

In the first issue of G, Richter explained his method on one of his early films, either Rhythmus 21 or Rhythmus 23, like so:

The film is a play of relationships of light.

The relationships of light have both qualitative and quantitative character: degree of brightness, proportions, etc., etc.

The forms that emerge are, de facto, l i m i t s of processes in different dimensions (or of dimensions in a different temporal sequence). . . .

The true means of construction is light—the intensity and quantity of light.

The task for the whole is to shape the nature of the light—in the sense of a comprehensive perceptibility. . . .

The forms that emerge are n e i t h e r analogies nor symbols nor means to beauty.

In its sequence of events (its screening), this film communicates very authentically the relationships of tension and contrast in the light. These relationships consist of light and dark, small and large, slow and fast, horizontal and vertical, etc., etc.

An attempt has been made to organize the film such that the individual parts stand in active tension to one another and to the whole, such that the whole remains intellectually [geistig] mobile within itself.

Later in his career, Richter would make more representational, figurative, and even narrative films. But in this early point in his career, he was intensely excited by the new medium’s capacity for radical abstraction—as well as its potential to encourage intellectual mobility and engagement.

Later in his career, Richter would make more representational, figurative, and even narrative films. But in this early point in his career, he was intensely excited by the new medium’s capacity for radical abstraction—as well as its potential to encourage intellectual mobility and engagement.

In G, Richter exhorted other artists to produce “elementary” films and called for filmmakers to delve deeper into visual possibilities of the medium. If Richter were here today, he might issue a new challenge: to discover what new sights and sounds the media of our time can make visible.

These films would pair well with the abstract animated films of Oskar Fischinger.

Also Walter Ruttmann could be included in the early productions of abstract films.