Lea esta publicación en español en el sitio web de la Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros (CPPC) »

In the mid-twentieth century, pioneering artists in Argentina and Brazil focused on a new form of art devoid of representational forms or symbolic meaning: Concrete art. Over the course of three years, the Getty Conservation Institute and Getty Research Institute collaborated on a research project to investigate this movement, resulting in the Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA exhibition Making Art Concrete: Works from Argentina and Brazil in the Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros.

While the Conservation Institute, with its tools for technical investigation, focused on the Concrete artists’ materials, techniques, and processes, the Research Institute drew on the wealth of art-historical materials in its Special Collections. This vast resource includes important primary sources relating to Concrete art, most notably the papers of the influential Uruguayan “constructivist” artist Joaquin Torres-García and an impressive collection of work by the Brazilian Concrete poetry group Noigandres.

Making Art Concrete features a selection of items from the Research Institute’s Special Collections, providing insights into the beginnings of Concretism in the 1940s in Argentina, as well as the debates surrounding the movement’s development in both Argentina and Brazil. The ephemeral materials related to Argentina—including magazines, flyers, pamphlets, and more—also shed light on the movement’s interdisciplinary nature; the artists forayed into and created alliances with poetry, theater, music, dance, architecture, and urban and industrial design.

Abstract, Constructivist, or Concrete?

The Dutch artist Theo van Doesburg coined the term “Concrete art” in 1930 to described a style that is not an abstraction from reality but reality itself—a pure invention that focuses on the immediate materiality of works of art.

Cover of Art Concret, 1930, Theo van Doesburg. Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed, Instituut Collectie Nederland AB5033

Both Van Doesburg and the constructivist Joaquín Torres-García were influential in Parisian abstract art circles in the 1920s and 1930s. Van Doesburg’s “Manifesto of Concrete Art,” published in the pamphlet Art Concret in 1930, envisioned an art based on “pure” forms with no reference to external reality, and art that would be exact in technique, objective, and universal. Torres-García, however, employed a constructivist grid but maintained certain figurative elements in his work.

By the 1940s, both artists became role models for the young Argentine artists who redefined Concretism according to their own political and aesthetic beliefs. Seeking to infuse everyday life with Concrete principles, in the mid-1940s, these artists worked to create a broad interdisciplinary movement that rejected both figuration and other forms of abstraction in favor of the “Concrete”.

Arturo and Argentine Concrete Art

In early 1944 young Argentine and Uruguayan artists launched their own magazine, Arturo, with a cover by Tomás Maldonado. Carmelo Arden Quin, Edgar Bayley, and Gyula Kosice edited the single issue, which is often viewed as the origin point of Argentine Concrete art. It was within Arturo’s pages that Rhod Rothfuss published his groundbreaking text “The Frame: A Problem of Contemporary Art.” He proposed that the frame and orthogonal painting were relics of pictorial realism and could be discarded within the context of abstract art. In response, artists began developing the shape of their paintings in accordance with the composition rather than a predefined structure (canvas and stretcher), an invention they called the marco recortado (cutout frame).

Cover of the first and only issue of Arturo: Revista de Artes Abstractas, with cover art by Tomás Maldonado. Buenos Aires, 1944. The Getty Research Institute, 1358-651. © Tomás Maldonado

Less often noted than Arturo’s programmatic critical essays and bombastic slogans demanding “INVENTION against AUTOMATISM” is its telling subtitle: “Journal of the Abstract Arts.” The plural “arts” was not incidental; it is indicative of the artists’ interdisciplinary, vanguard experimentation. They aimed to build a broad Concrete movement that extended beyond the confines of painting to the literary arts of poetry and theater, as well as the applied arts such as design and architecture.

Indeed, Arturo might be better described as a literary magazine than as an artistic one. It featured thirteen poems, three of which were composed by artists better remembered for their visual art, such as Torres-García and editors Gyula Kosice and Carmelo Arden Quin. In addition to a long poem titled “Divertimiento” (Diversion), Torres-García published the article “Con respecto a una futura creacion literaria” (With respect to a future literary creation), in which he addressed literary—not painterly—creation.

Diverging Groups and Debates

Segunda muestra: Arte Concreto in Buenos Aires. Flyer for the second exhibition of Concrete Art, 1945. The Getty Research Institute. © Estate of Grete Stern

In 1945 the renowned Bauhaus photographer Grete Stern hosted a meeting of the “inventionists” at her home. The event was organized by artists Gyula Kosice, Carmelo Arden Quin (co-editors of Arturo, along with the poet Edgar Bayley), and Rhod Rothfuss. Stern designed and collaged a flyer to advertise the meeting. It included photographs of the exhibition showing many works on paper on display, from musical scores to magazines. Magazines were mounted on the wall, suggesting an unconventional, nonhierarchical approach to exhibiting visual material.

The pamphlet also highlights different genres of art, listing each type of Concrete activity and its attendant qualities, according to the invencionistas. Poetry, for example, is defined in opposition to the current trends in literary existentialism. It is pared down to two essential qualities: “word” and “invented concept.”

The artists insisted on the rigorous definition and unique qualities of each genre and their independence from one another. For instance, painting is achieved with “compasses and ruler. Number and structure. Construction and order. The object of harmonic law.” Dance, by contrast, is described as “movements in space.” A year later, a more complete set of definitions was published in a separate pamphlet.

Elementarismo Utopico/Elementarismo Cientifico (Utopic Elementarism/Scientific Elementarism), unknown author. Undated, around 1945. The Getty Research Institute

Grupo Madí, Asociación Arte Concreto Invención & Perceptismo

In 1946, Kosice, Rothfuss, Arden Quin, and other artists who had exhibited their works at Stern’s house formed a group named Madí. They published prolifically, initially in cheap formats such as small flyers and one-sheet exhibition notices, and after 1947, through their magazine Arte Madí Universal. They eschewed staid formal conventions of presentation and were inventive in their printed materials, experimenting with die cutting, typography, orientation, and collage.

Madí Flyer, 1946, unknown author. The Getty Research Institute. The text states: “Madi has appeared to found a universal movement in art that will correspond to our industrial civilization and contemporary dialectical thought.” (“Madi aparece para fundar un movimiento universal de arte que sea la correspondencia estética de nuestra civilización industrial y del pensiamento daléctico contemporáneo.”)

The Madí artists used their publishing projects to lay claim to the invention of the marco recortado. Their flyers were cheap to reproduce and mimicked the format of political flyers, suggesting they may have been handed out in the street or at exhibitions.

Kosice and Arden Quin’s former collaborator on Arturo, Edgar Bayley, broke with them around 1945. He and his brother, Tomás Maldonado, formed the Asociación Arte Concreto Invención (AACI), along with artists Lidy Prati, Alfredo Hlito, Raúl Lozza, Martin Blaszko, and Juan Melé, among others.

By 1947, members of the AACI considered the marco recortado exhausted, so they returned to traditional rectangular formats. In turn, yet another split occurred: Lozza broke away from the AACI to create Perceptismo, a movement concentrating on the chromatic relationship between forms and planes. His companions were his aptly named two brothers, Van Dyck and Rembrandt, and the critic Abraham Haber.

Nueva Visión

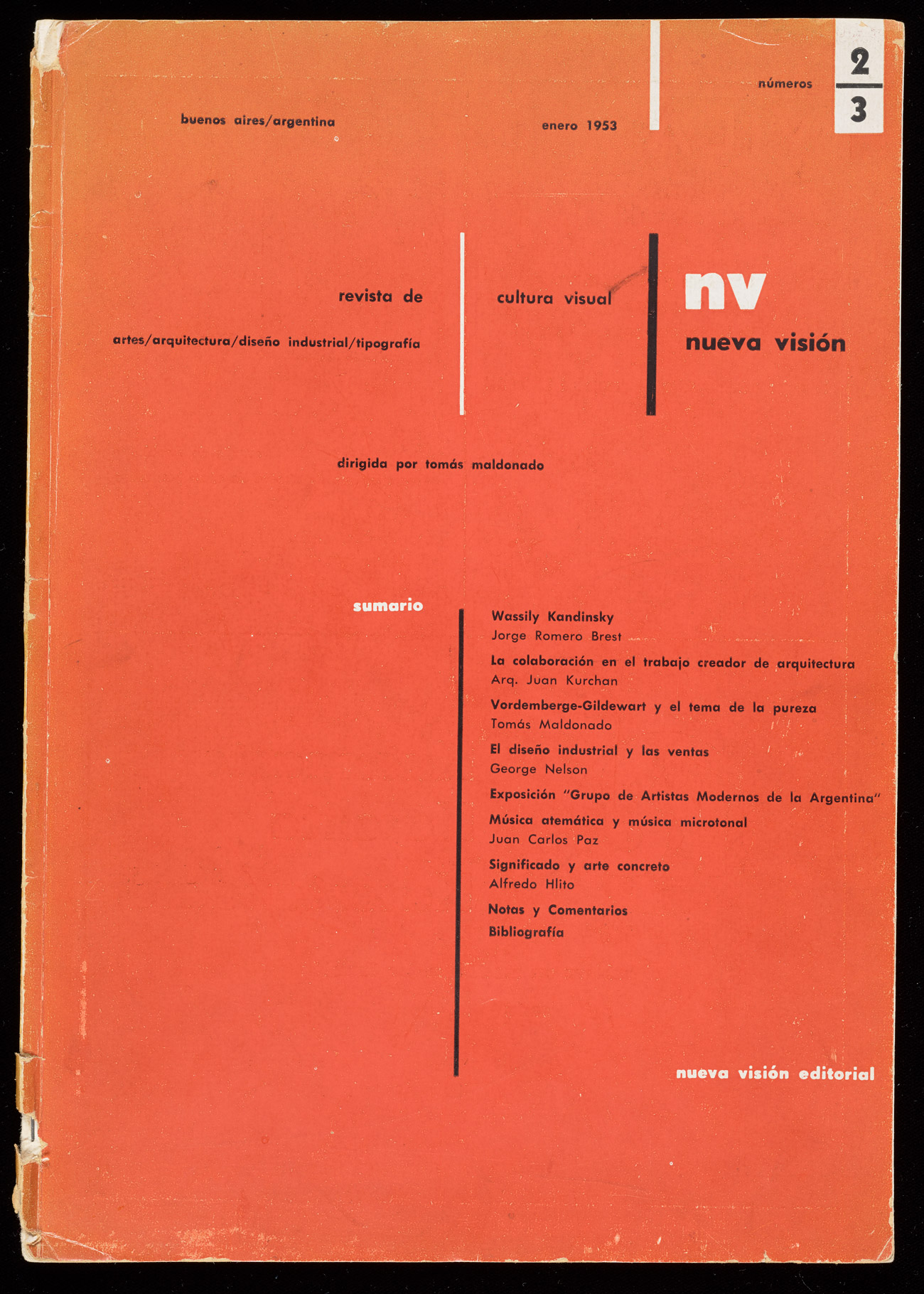

The AACI artists, particularly Maldonado and Hlito, focused on industrial design, typography, and architecture, disseminating their ideas through their magazine, Nueva Visión (New Vision). Compared to the Madí or Perceptismo artists, they were more aligned with the international modernist movement.

Cover of Nueva Visión. The Getty Research Institute. © Tomás Maldonado

Nueva Visión was a magazine concerned with contemporary industrial design, interior decorating, furnishings, and a certain emergent modern lifestyle. A focus on fine arts remained in an indirect way, however, with advertisements featuring unusual looking art objects affixed to the walls of modern abodes, with the copy declaring, “furniture for the home of our times” as well as art reviews.

The articles were intellectual and erudite but aimed to address modern society, boasting influential authors and diverse subjects. The art critic Jorge Romero Brest wrote about Kandinsky, and Hlito published an article on Concrete art. There were essays about the collaboration between artists and architects, industrial design and sales, atonal music, and an art review of the exhibition Grupo de Artistas Modernos de la Argentina.

Concrete artists expanded their reach to industrial design, leading some to some establishing their own furniture or commercial design companies. In some respects, this application of Concrete principles to design practices and a notion of mass consumption emerged from the earliest ideas of Concrete art. Its practitioners in Argentina hoped for an art that could merge with everyday life, that would be easy to understand, and therefore universal and accessible.

Installation view of Making Art Concrete: Works from Argentina and Brazil in the Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros at the Getty Center, showing the gallery presenting special collections material from the Getty Research Institute

Comments on this post are now closed.