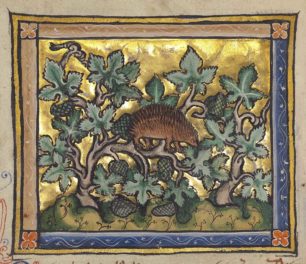

Griffin (detail) from Book of Flowers, 1460, unknown illuminator, made in France and Belgium. Parchment, 16 1/16 × 11 1/4 in. The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, National Library of the Netherlands, Ms.72 A 23, fol. 46

The bestiary—the medieval book of beasts—was among the most popular illuminated texts in northern Europe during the Middle Ages (about 500–1500). Medieval Christians understood every element of the world as a manifestation of God, and bestiaries largely focused on each animal’s religious meaning. The book brought creatures both real and fantastic to life before the reader’s eyes, offering Christian inspiration as well as entertainment.

The stories and images from the bestiary became so popular that they escaped from the book’s pages to inhabit a myriad of other art forms, ranging from magnificent tapestries to exquisitely carved ivories. In fact, the stories of the bestiary pervaded both medieval and modern popular culture. Even if you haven’t heard of the medieval bestiary, you will recognize many of its stories.

At the Getty from May 14 to August 18, 2019, Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World is the first exhibition ever dedicated to the bestiary and its influence. It gathers together more than a hundred works from institutions across the United States and Europe, including one-third of the world’s surviving illuminated bestiaries. As manuscripts specialists, curators of this exhibition, and editors of the accompanying book, in this post we introduce key stories from the bestiary, describe the contents of a typical bestiary, and explore the bestiary’s centuries-long influence.

How Bestiaries Work—The Unicorn

The unicorn offers a primary example of the bestiary’s complex symbolism, as well as its influence on both medieval and modern imaginations.

The unicorn was described in the text of the bestiary as a wild, untamable beast that could be captured only by a maiden in the woods. Upon meeting the maiden, the unicorn would lay its head in her lap, making it vulnerable to the attack of hunters.

Unicorn (detail) from The Ashmole Bestiary, about 1210–20, unknown illuminator, made in England. Parchment, 10 7/8 × 7 3/16 in. The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, Ms. Ashmole 1511, fol. 14v

In the bestiary, however, the unicorn’s appearance and capture were only half the story. The unicorn also symbolized the Incarnation, the moment when Christ was conceived in the womb of the Virgin Mary, rendering him human and vulnerable to death. In the luxurious image shown above, the beast rests in the lap of a maiden seated before a tree, while a hunter on the right stabs the animal in its side. The unicorn symbolizes Christ and the maiden represents his mother the Virgin Mary, while the killing of the creature serves as an allegory for Christ’s death.

The widespread diffusion of the bestiary popularized the unicorn’s tale, which was adapted in many other media in addition to manuscripts. At the center of this carved bone saddle, for example, a stately unicorn looks over its shoulder at an elegant maiden, echoing the bestiary story.

Thanks to its proclivity for maidens, the unicorn also became a focus of stories of romance and chivalry, transforming from a religious symbol into an emblem of courtly love.

Parade Saddle, about 1450, unknown creator, made in Germany or Tyrol. Bone, polychromy, wood, leather, iron alloy, 16 1/2 × 17 × 21 9/16 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1904, 04.3.250. Image: www.metmuseum.org

Text and Image in the Bestiary

Medieval bestiaries contained anywhere from a few dozen to more than a hundred descriptions of animals, each accompanied by an iconic image. Some descriptions explained a creature’s Christian significance, such as the unicorn as a symbol for Christ, while others focused on physical characteristics. The selection and order of the beasts varied, though many bestiaries divided them into a hierarchy of land animals, birds, serpents, and sea creatures. The bestiary was originally intended for religious education within the church, but it was eventually sought after by wealthy members of society for devotional reading as well as entertainment.

The Lion

Lion (detail) in a bestiary, about 1225–50, unknown illuminator, made in England. Parchment, 11 5/8 × 7 1/2 in. The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, Ms. Bodl. 764, fol. 2v

The lion was known in the bestiary as the “king of beasts,” and as such, was placed first. In this spectacularly colorful image, a jaunty lion waves to the viewer at top. In the middle, three cubs playfully crawl over their adult counterpart. At bottom, cubs are brought to life by their parents, who lick and breathe on them. According to the bestiary, lion cubs are born dead, and after three days their parents literally breathe life into them. This behavior was believed to have been put into the lion at the beginning of time by God as a reflection of the Crucifixion of Christ and his Resurrection three days later.

Land Animals

Parandrus in a bestiary, about 1200–1210, unknown illuminator, made in England. Parchment, 8 11/16 × 6 5/16 in. The British Library. Image: Granger

After introducing the lion, the typical bestiary presented a section devoted to land animals. According to the text in this example, the four-legged beast depicted at bottom can move its long horns independently, so that one can face forward and the other backward to defend against dual threats. The artist emphasized this flexibility by showing one of the animal’s horns slicing through the text itself. Such interaction between text and image was a hallmark of the bestiary tradition.

Birds

Eagles (detail) from a Workshop Bestiary, about 1185, unknown illuminator, made in England. Vellum, 8 7/16 × 6 1/8 in. The Morgan Library & Museum, New York, Ms. M.81, fol. 48

This opening shows a manuscript’s transition from land animals to birds. Just as the lion was known as the king of beasts, the eagle was supreme among birds. The eagle was described as losing its sight as it grows old, only to be rejuvenated by gazing at the sun.

Serpents

Dragon in a bestiary, about 1240–50, unknown illuminator, made in England. Parchment, 11 × 6 1/2 in. The British Library,London, Harley Ms. 3244, fol. 59. Image: Granger

Serpents often came next. This page depicts the dragon, king of serpents, with a fire-breathing specimen stretching diagonally across the page. The section of the text that describes the power of the dragon’s tail is visually interrupted by the tail itself, demonstrating the formidable nature of the beast as well as the meaningful ways in which text and image interacted in the bestiary.

Whale (detail) from a bestiary, about 1270, unknown illuminator, made possibly in Thérouanne, France. Tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, 7 1/2 × 5 5/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XV 3 (83.MR.173), fol. 89v. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Sea Creatures

The final section of the bestiary usually dealt with sea creatures. Here an enormous whale plunges into the depths, dragging two hapless fishermen with it. The text describes this beast as so massive that sailors confuse its back for an island. When they make camp and light a fire, the whale feels the heat and dives down, drowning its surprised visitors. This story is presented as a warning against the deceptions of the devil. The artist skillfully evokes the sense of horror felt by the sailors at the exact moment they discover their tragic mistake.

Beasts Beyond the Bestiary

The bestiary’s stories and images were so popular that medieval artists readily adapted them for other kinds of manuscripts, as well as for various other types of art.

Because many bestiary animals communicated complex religious messages, they often appeared in liturgical and devotional contexts where worshippers could easily link them to Christian ideology. But the well-known characteristics associated with numerous beasts—the unicorn, the elephant, and the fox, among others—also made them an ideal match for secular artworks made for the elite world of the court. Over time, the memorable creatures that were central to the bestiary tradition pervaded the visual vocabulary of the medieval world, becoming some of the most common symbols in art of the Middle Ages.

Bronze candlestick in the form of an elephant carrying a Howdah, about 1200–1400, unknown creator, made in Germany. Bronze, 6 5/8 × 2 1/16 × 4 1/16 in. Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 1595-1855. Image © Victoria and Albert Museum

For example, the elephant appears as a symbol of strength in artworks of many media, including this metal candlestick. The howdah, a structure used to carry soldiers on the back of an elephant, was a symbol of the animal’s might. This candlestick is ingeniously shaped so that the pricket (spike) for the candle stands on the upper tower of the howdah, while the crenellated edge of the tray is designed to catch the wax.

Reynard Disguised as a Doctor before King Noble (detail) from New Adventures of Reynard, after 1292, Jacquemart Giélée, made in France. Parchment, 11 3/16 × 7 7/8 in. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, Ms. fr. 372, fol. 36

The fox was described in the bestiary as a trickster that would roll over on its back and pretend to be dead, luring unsuspecting birds into its midst. The fox would then snap its jaws shut on the birds that had fallen for the ruse. Tales of the fox spread far and wide in the Middle Ages, even informing popular literature of the period.

A series of medieval moral stories with animal characters revolves around a trickster fox named Reynard. A lion called Noble, the literal king of beasts in the tale, often tries to hold Reynard accountable for his ploys. The tales of Reynard became so popular in France that the common word for fox in modern French does not derive from the Latin term vulpus, but is actually the word reynard.

Tapestry with Flowers and Animals, about 1530–45, unknown creator, made in Belgium. Wool, silk, tapestry weave, 11 ft. 6 7/8 in. x 13 ft. 1 3/4 in. Minneapolis Institute of Art, Gift of Mrs. C.J. Martin in memory of Charles Jarius Martin, 34.4

The animals in this millefleurs (thousand-flowers) tapestry seem at first to be scattered randomly for purely decorative effect. Yet the stag, the unicorn, and the lion were all associated with Christ in the stories of the bestiary. Their careful placement in this tapestry, forming a vertical row of three within the triangle created by the rosebushes, strengthens the group’s resonance with the Christian concept of the Trinity—the three manifestations of God as the Father, the Son (Christ), and the Holy Spirit.

Lion in the Rothschild Pentateuch, 1296, unknown illuminator, made in France and Germany. Tempera colors, gold, and ink, 10 13/16 × 8 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Acquired with the generous support of Jo Carole and Ronald S. Lauder, Ms. 116 (2018.43), fol. 32v. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

The use of animals as allegories for human virtues and vices was not limited to European Christian art, but was a widespread phenomenon that transcended geography and religion. In this Hebrew Bible, the bestiary image of a father lion breathing life into his dead cub accompanies the passage in Genesis in which God commands Abraham to sacrifice his son Isaac. According to some rabbinic commentaries, Abraham actually killed Isaac, but Isaac was miraculously brought back to life. For Christians, the tale of the lion was seen as a reference to Christ’s death and resurrection, but here a Jewish audience might have viewed it within the framework of the story of Abraham and the revival of Isaac.

The Bestiary and Natural History

The medieval bestiary was never intended as a scientific work, but much of its lore was eventually incorporated into the nascent field of natural history. The period of the bestiary’s greatest popularity, from about 1100 to 1300, corresponded with a movement to create encyclopedias that would gather all knowledge. Many of these encyclopedias included a section devoted to animals, which relied heavily on the bestiary but often stripped away the Christian symbolism.

At this same time, the European conception of the world was being broadened by a growth in trade and travel that increasingly linked Western Europe with other parts of the globe. In the developing field of cartography, maps and navigational charts represented the world’s creatures in their respective regions.

The Griffin

Ibex Horn (“Griffin Claw”), 1500s or earlier (horn), about 1575–1625 (mount), unknown maker, England. Ibex horn with a silver mount, 28 in. wide. Trustees of The British Museum, London, OA.24. Image © The Trustees of the British Museum

The griffin is one of only a few animals to be illustrated in what is often identified as the first medieval encyclopedia, known as the Book of Flowers (see image at the top of this article). A mythical hybrid between a lion and an eagle, the griffin was believed to carry away full-grown men to feed its young; this legend is found in ancient texts as well as the medieval bestiary. The griffin’s featured presence in this book—along with its alleged remains in church treasuries across Europe—attests to its central place in the medieval imagination.

The griffin’s presence in such texts lent credibility to supposed griffin claws (usually ibex horns), which were highly prized as physical specimens well into the late sixteenth century. An inscription on the mount identifies this example as belonging to the shrine of Saint Cuthbert in Durham, which recorded two such claws in addition to several “griffin eggs” (probably ostrich eggs) in an inventory from 1383.

Nautical Chart, 1586, Mateo Prunes, Spain. Parchment, 46 1/16 x 27 9/16 in. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, GE AA-570

Medieval maps were often oriented with south on the left and north on the right. In this chart made for navigation at sea, many animals occupy the left-hand portion representing Africa. Creatures such as the unicorn, camel, and lion reflect the medieval perception of far-flung lands as exotic and perhaps dangerous.

The Legacy of the Bestiary

In the visual arts, the rich legacy of the bestiary lasted far beyond the Middle Ages. Twentieth-century artists revived the pairing of animal imagery and text, calling their creations “bestiaries” after the medieval example. Today the term often refers to any collection of descriptions of animals, whether in words or images, but not necessarily with associated allegories or Christian connotations.

Writers and artists revived the genre of the illustrated bestiary in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, when a variety of new poetic and prose texts of animal lore appeared with illustrations created by established artists and printmakers.

Dolphin, from Le bestiaire, oucortège d’Orphée, 1911, Raoul Dufy and Guillaume Apollinaire, France. Woodcut, 13 in. Special Research Collections, UCSB Library, University of California, Santa Barbara. Image © 2019 Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

A notable example of the early twentieth-century bestiary was the French poet Guillaume Apollinaire’s foray into illustrated fine art books. Apollinaire’s text was eventually published with thirty wood engravings by Raoul Dufy. Dufy’s wood engravings of animals are bold and forceful, with large swaths of deeply imprinted black ink contrasting with the milky white paper, imitating the block-book style of the early printed images of the fifteenth century.

The human relationship to the animal world is today a subject of intense interest and even debate, with the animals themselves caught in between as questions of conservation and environmental change are addressed by scientists, politicians, and activists. Contemporary artists, too, respond to these questions, participating in a long tradition of depicting animals in art that offers a commentary on the role of animals in our world.

Pray, 2012, Kate Clark. Antelope hide and horns, foam, clay, pins, thread, and rubber eyes, 36 x 33 x 17 in. Collection of Chet Robachinski and Jerry Slipman. © Kate Clark

The taxidermy hybrid creatures created by contemporary sculptor Kate Clark speak to the ubiquitous tendency of humans to see themselves in animals. Clark often “upcycles” hides that taxidermists or hunters don’t want. This work, entitled Pray, crystallizes this impulse, combining as it does an animal body with a human face that seems uncannily animate, reaching out across space and compelling the viewer to engage with the creature directly. As the medieval bestiary used animals to teach moral lessons, the fusion of human and animal in Clark’s work invites viewers to examine their natural instincts, the animal within, and the characteristics that unite disparate animal kingdoms.

_______

We hope this introduction has intrigued you to learn more about the medieval bestiary. On the occasion of our exhibition, we have created multiple new resources on the medieval bestiary, which we invite you to explore:

- An in-depth catalogue with essays by 25 leading scholars exploring text and image in the bestiary, the influence of bestiaries on natural history in the early modern world, and the legacy of the bestiary today.

- A series of live videos on the Getty’s Facebook page in which we introduce key animals from the bestiary through manuscripts in the Getty’s collection.

- Profiles of 18 bestiary animals here on The Iris written in conjunction with Professor Meredith Cohen, professor of art history at UCLA, and her art history undergraduate students.

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.