Personal experience is often the springboard for new understanding, as manuscripts curator Kristen Collins reflects during the closing days of Canterbury and St. Albans

Inside Canterbury and St. Albans at the Getty Center. Pages from the St. Albans Psalter, foreground: Bibliothek Hildesheim. Stained-glass panels from the Ancestors of Christ Windows, Courtesy Dean and Chapter of Canterbury

We are in the last week of the exhibition Canterbury and St. Albans, closing this Sunday, February 2. My co-curator Jeffrey Weaver and I put several years of research into the monumental panels of stained glass and luxuriously illuminated manuscript pages on loan for the exhibition—so you might assume that my thoughts on these works were fully formed, edited, and committed to the exhibition’s object labels and book by the time we installed the artwork in our galleries. But the thing about exhibitions is this: writing the labels and installing the art are just the beginning. Exhibitions create the staging ground for the conversations that happen in the presence of the objects, the lectures, tours, and convenings that are inspired by them, and the questions that are asked by our visitors, and ourselves, as we spend time with the objects.

As curators, we decided that the way to present these objects in one show was to emphasize their differences: the monumental and the miniature, glass panels meant to be experienced by the monks in the communal space of the choir at Canterbury alongside a book meant for private devotion, outside the spaces of the church. The thematic thread weaving together these works became one of juxtaposition.

Stained glass illuminates the heights of Canterbury Cathedral in this view from the choir

And yet, with the exhibition’s very first lecture, the objects were thoughtfully and evocatively joined together. In his remarks at the exhibition’s opening, the Very Reverend Dean Robert Willis of Canterbury talked about how seeing the glass on display with the splendidly illuminated book of psalms made him think in a new way about the intertwined nature of art and prayer within the spaces of Canterbury.

Exhibitions also remove objects from one context and place them in another, a change that allows them to speak to one another in new ways, to generate a new energy. And sometimes the deepest insights come when we are taken from our own context, finding new ways to see. As with Dean Willis, this happened to me.

My family and I were lucky enough to attend Christmas services at Canterbury Cathedral, and on December 29 were there for the feast-day of Thomas Becket. I’d previously visited Canterbury as a scholar—seeing some of the greatest of the Ancestors of Christ panels in the conservation lab and exploring the church—but over the holiday I was able to experience the art and spaces of the church slowly, seated in the choir, joining others in song and watching the light gradually fade from the windows that ring the space. The processions of the priests in their embroidered robes, the gleaming Gospel book that was lifted from the altar and carried into the church where the Dean read from the Gospel of John, and the psalms sung in Latin for the Becket feast were, for me, transformative moments. They changed not only the way I saw the glass, but the way I understood the St. Albans Psalter.

Inside the choir of Canterbury Cathedral, Christmas 2013. Photo: Mary Collins

A look inside the Stained Glass Studio at Canterbury Cathedral. Foreground: Lamech from the Ancestors of Christ Windows, Canterbury Cathedral, England, 1178–80. Colored glass and vitreous paint; lead came. Photo: Kristen Collins

We know that the Psalter was likely owned by the nun Christina of Markyate. As her personal prayer book, it would have allowed her to mirror the activities of the monks at St Albans, who recited the 150 psalms in church throughout the week. Living with a small community of women at Markyate, on the borders of St. Albans’ properties, she would probably have had Mass said by a visiting priest. While Markyate had a chapel, it would have offered a much more modest display than the services offered at the nearby abbey church of Saint Alban.

As scholars, we are taught to be analytical as we weigh evidence for the date, place of origin, and probable owners of artworks. My recent visit to Canterbury allowed me to experience the spaces of the church in a whole new way, which in turn prompted me to think about the manuscript as a kind of personal liturgical space. Small and portable, one needed only to open the book to enter.

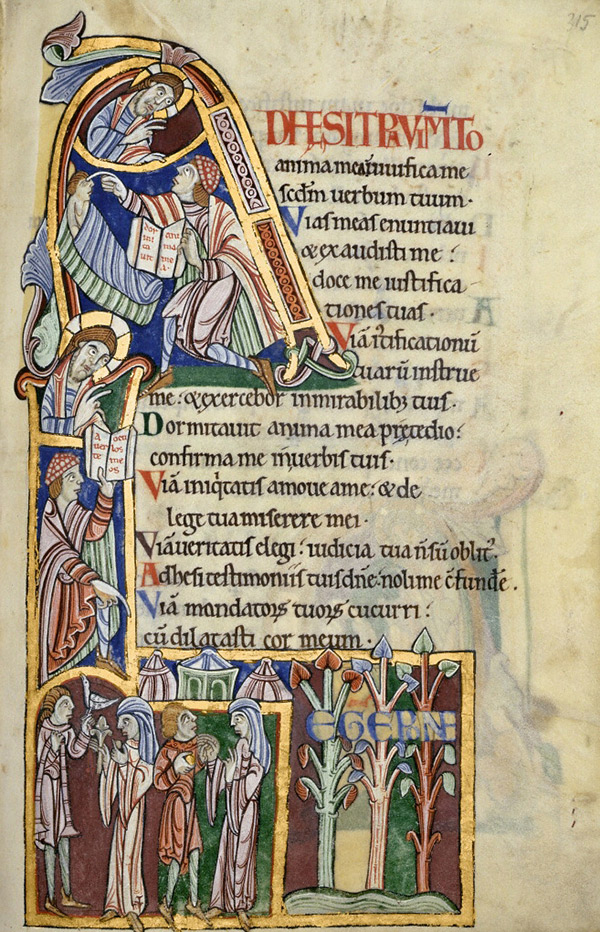

Initial A: Psalm 118:28 and Psalm 118:37 in the St. Albans Psalter, about 1130. Tempera and gold on parchment, 12 3/16 x 8 5/8 in. Dombibliothek Hildesheim

For Christina, the Psalter did much more than simply present the texts that formed the spine of the weekly church services. We have to imagine her handling the book, turning the pages, lifting the curtains that covered the luxuriously painted illuminations, and seeing lamplight shimmer on gilded details as she sang the Psalms. The Psalter would have offered a hint of the splendid display of light, color, and ceremony that in the Middle Ages was otherwise found only in the spaces of a church.

Canterbury and St. Albans: Treasures from Church and Cloister closes at the Getty Center on February 2. The stained glass windows from Canterbury Cathedral will then go on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cloisters, while the St. Albans Psalter will return to the Hildesheim Cathedral Library, where it will soon be rebound as a single codex.

Enjoyed my visit to your exhibit, I visited twice! Could you possibly tell me how you translated the texts or what version of the Bible you might have used? Loved your methodology!

Congratulations on the exhibition and publication. Thank you Kristen Collins and the Department of Manuscripts for making it possible to see this major work in L.A.