Venetian Renaissance painter Giovanni Bellini is widely considered one of the greatest Italian artists of all time. His landscapes are imbued with allegory and a reverence for nature. In this episode, we listen as two curators, Davide Gasparotto and Keith Christiansen, visit the Getty Museum’s exhibition Giovanni Bellini: Landscapes of Faith in Renaissance Venice to talk about a selection of paintings on view.

Gasparotto is senior curator of paintings at the J. Paul Getty Museum and Christiansen is the John Pope-Hennessy Chairman of the Department of European Paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It is recommended to view images of the paintings online while listening.

More to Explore

Giovanni Bellini: Landscapes of Faith in Renaissance Venice exhibition information

Giovanni Bellini: Landscapes of Faith in Renaissance Venice publication information

Transcript

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

KEITH CHRISTIANSEN: Throughout all these pictures, regardless of subject, there’s a serenity. They were pictures that are meant for meditation, for standing in front of, for projecting your own thoughts on them. They invite prolonged viewing.

DAVIDE GASPAROTTO: Yes.

CUNO: In this episode, curators Davide Gasparotto and Keith Christiansen discuss a series paintings by the Renaissance master Giovanni Bellini.

The sixteenth-century Florentine painter and biographer Giorgio Vasari wrote of Venetian Renaissance painter Giovanni Bellini that he “kept growing in credit and fame, and became so excellent that he was the greatest and most renowned man in his profession.”

Bellini was especially adept at painting the light and nuance of landscape. Over the course of the sixteenth century, his landscapes assumed a prominence unseen in Western art since classical antiquity. Thirteen of his remarkable paintings were on display in the recent Getty exhibition Giovanni Bellini: Landscapes of Faith in Renaissance Venice.

In this episode, I asked two curators, Davide Gasparotto and Keith Christiansen, to visit the Bellini exhibition to talk about the paintings and why they find Bellini’s compositions so captivating. Davide is senior curator of paintings at the J. Paul Getty Museum and Keith is the John Pope-Hennessy Chairman of the Department of European Paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Davide and Keith discuss the paintings in great detail; I encourage you to visit our website to view images of the paintings or look them up elsewhere online while listening.

GASPAROTTO: So we can start?

BACKGROUND VOICES: Yeah, whenever you’re ready.

CUNO: Davide and Keith started with three paintings that feature the Crucifixion in different contexts and landscapes, ranging in size from 20 to 30 inches high by 11 to 20 inches wide. The first painting they discussed was Crucifixion, circa 1495 to 1500, from the collection of the Banca Popolare di Vicenza. It prominently features Christ on the cross with an assortment of buildings in the background and a graveyard scene with tombstones and skulls in the foreground.

GASPAROTTO: As you know, Keith, this was the starting point for me to—for thinking to an exhibition on Giovanni Bellini and landscape. Obviously, the painting is amazing on several respects because of the incredible condition. But I was always attracted by the composition. The fact that the cross is really sort of planted, but it’s in the threshold between us, between the viewers and the painting, the fictive space of the picture. And then this sort of landscape now, it opens up on—in the background and it creates this incredible poetic atmosphere, poetic mood.

CHRISTIANSEN: Yeah, I remember going to Prato, because this was owned by, at that time, the bank, the [GASPAROTTO: Yes.] Cassa di Risparmio of Prato. I was a graduate student going to the museum to see something entirely different. And this came as a incredible discovery, standing before the picture, with this extraordinary image of Christ on the cross brought up right to the edge of the picture plane, set on a rocky plateau. And then beyond this, this abundant nature, so rich. And for anybody who’s traveled in Italy, one realizes that it’s richer than any particular location. It’s an accumulation of virtually everything that he’s been feeling about nature. And then with these extraordinary tombstones set about in the landscape with Hebrew or pseudo Hebrew inscriptions on them. The skulls in the foreground, so that you’re made immediately aware that it’s a meditation on mortality.

GASPAROTTO: Mm-hm, because [CHRISTIANSEN: And—] usually there is only one skull; here, there are all [CHRISTIANSEN: That’s right.] these skulls. There are these tombstones.

CHRISTIANSEN: And then you begin to notice that the trees are barren. At which point you then notice that there are new shoots coming out of one tree, one cut-down tree stump on the left. It’s still in full foliage at the top. Once again, mortality and resurrection. And then there’s this extraordinary path that winds back past a cliff, past a mill, where you see a millstone leaning against a country house. And in the distance, this extraordinary city with church towers, with domes. And behind that, a further landscape and a figure walking alone on the path towards the city. And this, to me, over the years of thinking about this picture, seeing it again and again, each time entering with a sort of renewed awe at its richness, one realizes it’s a pilgrimage of life. And that it’s a story of the path of life, the path of the soul, from the city of man to where he faces his own mortality. And this seems to me to register so clearly with its function as a private devotional work for somebody sitting before it.

GASPAROTTO: Yes, yes. And this—obviously, this theme of the private subjects from Christian tradition, [CHRISTIANSEN: Yeah.] which Bellini, in some way, is able to transform in a real presence, as something which is really happening now.

CHRISTIANSEN: I think that one of the most extraordinary things about Bellini is that you don’t ever feel that you’re in the presence of somebody who has made painting an intellectual enterprise. There’s a quality of empathy in his painting.

GASPAROTTO: Absolutely, yeah.

CHRISTIANSEN: And it’s that empathy that is communicated. I’ve never known anybody who has gone to Venice who does not have a direct response to Bellini’s work.

GASPAROTTO: Yes.

CHRISTIANSEN: There’s a human connection. He understands the humanity in any given subject. And in this one, you know, the graining of the wood. Who would’ve thought of this intense graining of the wood?

GASPAROTTO: [over Christiansen] You mean in the cross.

CHRISTIANSEN: In the cross.

GASPAROTTO: Yeah, yeah, it—

CHRISTIANSEN: [over Gasparotto] It gives it such a concrete physical presence.

GASPAROTTO: [over Christiansen] Yeah, yeah. To define—

CHRISTIANSEN: [over Gasparotto] Yeah. And then you look at the feet, and there is this very beautiful, semi-transparent trickle of blood dripping down the cross. And it becomes a real emblem of tragedy, without in any way slipping over into something violent or overly emphatic.

GASPAROTTO: And I always admire this incredible detailed representation of flowers and plants. I think some botanists recognize like more than thirty species of plants. But I was always a little bit hesitant in interpreting everything so precisely as a symbol of something. I don’t know what you think about—

CHRISTIANSEN: [over Gasparotto] Yeah. I think that he’s a kind of Wordsworthian nature poet, in a Christian sense. And his vision embraced all of nature. His father was already a close observer of nature.

So I think this was passed onto him.

GASPAROTTO: Yeah.

CHRISTIANSEN: In the same way that the skulls have—these one, two, three, four five, [GASPAROTTO: Five skulls.] skulls, each one at a different angle.

GASPAROTTO: Yeah. Yeah.

CHRISTIANSEN: [over Gasparotto] And they always remind me—there’s a great still life by Cézanne of a group of skulls on a table, which is his meditation on mortality. And I think that’s clearly what Bellini’s thinking of, don’t you?

GASPAROTTO: Yeah. Yeah, I think so. I think so. And to me, this idea that everything is precisely tied to a specific significance, the meaning of the element, it does not do justice to the complexity, the overall complexity, the overall ability to really build a complex, but also a unified image.

I don’t know what you think about his way of building up these sort of ideal cities, this ideal Jerusalem. And if you believe that some of the buildings, which are recognizable, one of the buildings is Cathedral of Vicenza, the other one is Cathedral of Ancona, and there are some towers. The tower from Vincenza. Do you think they can have a meaning? Or it was just his way of building up an ideal city, using elements from buildings that he saw, that he probably draft?

CHRISTIANSEN: Yeah, my own view is that Bellini’s art defines the border between a shared experience in the real world and the transformation of that experience into something of a world beyond us. In this case, the sacred world.

GASPAROTTO: Yes.

CHRISTIANSEN: And this is the intersection, and he gathers together in his notebooks, none of which survive, but he obviously had extraordinary, rich notebooks of studies of plants, studies of buildings that attracted him in his very rare travels—’cause he was basically a sedentary artist. Venice and his villa were really the two locations.

And he puts them together and creates a sacred reality. For me, that’s what it is. But I also think that these are pictures, and this is of an overriding importance for a transition in European painting. They’re not pictures that are codes. They’re pictures that are suggestive. And they were intended for people like you and me to stand in front and look at, and to talk about what we think is going on. In that sense, it’s a new kind of painting. And it’s a painting for the amateur, for art lovers.

GASPAROTTO: For art lovers. So they are—

CHRISTIANSEN: [over Gasparotto] And it’s important that they be open-ended. That they not be able to—

GASPAROTTO: [over Christiansen] They were not only just devotional tools, but they were able to—yes.

CHRISTIANSEN: And you know, there are pictures, such as a great painting of Saint Francis in the Wilderness, at the Frick Collection, where one isn’t sure what the specific literary source is. And my contention is there is no literary source. It exists alongside poetry and literature. It’s an equivalent.

GASPAROTTO: [over Christiansen] An equivalent but for sure maybe with a strong component from the canticles of the creatures. So this idea that the painting is a sort of a celebration of the beauty of the world, of the of the beauty of the physical world, which is the manifestation, the physical manifestation of God, basically.

CUNO: Davide and Keith then moved on to another painting, this one dated circa 1475, from the Corsini Collection in Florence. Again, this painting is dominated by Christ on the cross but, as you’ll hear, in a very different landscape.

GASPAROTTO: I wanted to ask you about the difference with a painting from the Corsini Collection in Florence, where we have again a crucifixion with an isolated…

CHRISTIANSEN: Figure.

GASPAROTTO: …figure. But the landscape here looks kind of different. The mood is totally different to me. The Vincenza is more serene, and there is a serenity. And here, there is a profound melancholy, which is really echoed in this—

CHRISTIANSEN: In the landscape.

GASPAROTTO: In the landscape.

CHRISTIANSEN: I feel exactly the same way. First of all, it’s an extraordinary composition.

GASPAROTTO: Yes.

CHRISTIANSEN: It’s divided vertically by the cross, with this wonderful horizontal of the cross beams. The arms swoop down, and the arms are exactly echoed in the landscape, in two hills that make great curves either side. So from a formal point of view, it’s an absolute perfect composition

GASPAROTTO: [over Christiansen] Perfect composition, yes.

CHRISTIANSEN: But in that nestled curve of the landscape, you move then to an infinite distance. And it’s underscored by, again, these horizontal clouds on the horizon. It’s a little like standing on the edge of the Pacific Ocean…

GASPAROTTO: Yes.

CHRISTIANSEN: …where you look out and there’s infinite distance. And that infinite distance makes one feel very small. And it’s there that you get the tragedy of the Christ, [GASPAROTTO: Of the Christ, yes.] in the front. And it makes me think, you know, of Caspar David Friedrich where he always puts a figure in the foreground silhouetted against a distant landscape.

GASPAROTTO: Yes.

CHRISTIANSEN: And it’s that quality of, once again, a different kind of mortality. But the distant horizon assumes a really symbolic character.

GASPAROTTO: Yeah, and this also, you know, has something to do, I believe, with the sort of Flemish models that Bellini was looking at to—

CHRISTIANSEN: [over Gasparotto] But he transforms them.

GASPAROTTO: Transforms—

CHRISTIANSEN: [over Gasparotto] Totally transforms them. And once again, it’s the natural setting that becomes a vehicle for the emotional content. And that, I think, is really extraordinary.

GASPAROTTO: Yes, yes.

CHRISTIANSEN: [over Gasparotto] It’s not just a backdrop.

GASPAROTTO: [over Christiansen] It’s not a backdrop of—

CHRISTIANSEN: [over Gasparotto] It is a conveyor of meaning and of mood, of mood.

GASPAROTTO: [over Christiansen] It’s a—I think it’s the great thing about Bellini, and is a way, it’s clear from the entire exhibition that the landscape sort of becomes protagonist, as much as the figure.

CHRISTIANSEN: That’s right.

GASPAROTTO: Creates the mood, helps the viewer to immerse himself or herself into the realm of the picture, into the realm of the Christian subject.

CHRISTIANSEN: And it reminds one of that wonderful sequence of letters about a painting that he was to do for Isabella d’Este, in which in the end, the great poet Bembo informs Isabella d’Este that Bellini doesn’t like to be constricted by artistic programs. And it’s in the landscapes that he feels most comfortable, and he likes to wander about in his landscapes. And this is an invitation to the viewer to wander about imaginatively in the landscape. And I think this is one of the reasons they’re so richly articulated because he wants to give that potential of being able to explore.

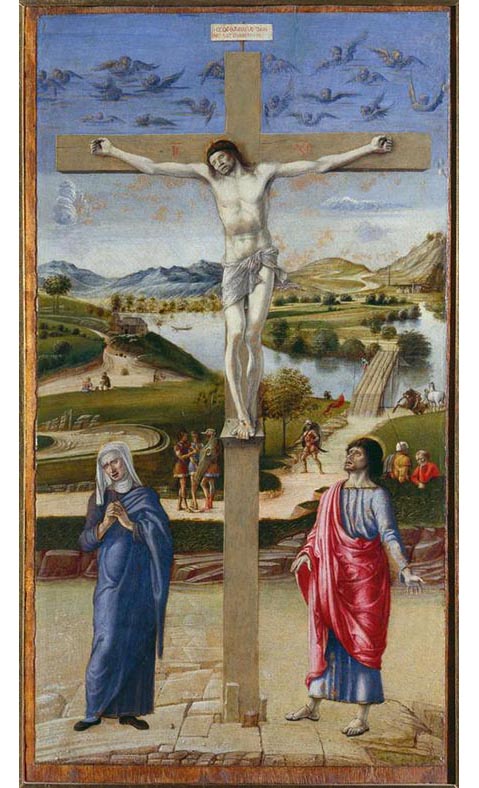

CUNO: The next painting they looked at was Crucifixion with the Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist, circa 1458 to 1459, from the Museo Correr in Venice.

GASPAROTTO: I think that perhaps the painting from the Correr Museum, which is in some way more traditional, because we have at the foot of the cross, the figures of the Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist. The landscape here is really amazing—what about you are saying about the richness and the details and the things that are happening here in these incredible landscapes.

CHRISTIANSEN: [over Gasparotto] Yeah. I was so glad you included this for two reasons. Numbers one, this is one of the few pictures that really can be dated with some real confidence, because of its relationship to a dated manuscript. And anybody who looks at the small images of winged cherubim up above with the use of gold on their wings realizes it’s a miniature frame of mind.

GASPAROTTO: [over Christiansen] It’s—yeah, it’s—

CHRISTIANSEN: [over Gasparotto] But the second part is that you have not just Christ on the cross, but you have his mother mourning his death, and his beloved apostle, on this rocky ground. And they’re taken directly over from a narrative kind of point—the traditional way that this is shown derived directly from this brother-in-law, Andrea Mantegna.

GASPAROTTO: [over Christiansen] Andrea Mantegna. A sort of a stage, yeah.

CHRISTIANSEN: [over Gasparotto] A stage. It’s a stage.

CHRISTIANSEN: The stage— the stage that you talk about is obviously abstracted. The rock formations.

GASPAROTTO: Yes, yes.

CHRISTIANSEN: And then beyond that, you move into this incredibly green landscape. And it’s the river, this winding river, with the bridge, with a boat, with a house, with the leaves rendered in a marvelous technique that gives them almost this quality of movement.

GASPAROTTO: And the reflections [CHRISTIANSEN: And the reflections.] of the leaves on the water.

CHRISTIANSEN: [over Gasparotto] That’s Netherlandish.

GASPAROTTO: That’s Netherlandish.

CHRISTIANSEN: [over Gasparotto] That’s incredibly Netherlandish.

GASPAROTTO: Yeah, yeah.

CHRISTIANSEN: So he brings together the Italian, the Netherlandish. And we can watch the progress in these three pictures of how he brings them together through his own study of nature.

GASPAROTTO: [over Christiansen] his own of—

CHRISTIANSEN: [over Gasparotto] But he starts—the impetus are two traditions.

GASPAROTTO: Yes.

CHRISTIANSEN: And he sees the one for its rich memetic quality, the other for its extraordinary dramatic, empathetic quality.

GASPAROTTO: Yeah, yeah. And also the color also in these paintings I really like very much. And the precision of the brushstrokes. No, it’s really reminding of illumination, I think—these very bright colors.

CUNO: Davide and Keith next turned to Sacred Allegory, circa 1500 to 1504, from the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. This painting measures almost 29 inches tall and 47 inches wide.

CHRISTIANSEN: You’re looking at a picture with an enclosure, with an elaborate, [GASPAROTTO: Beautiful pavement.] elaborate pavement. You know, it’s a pavement that you would expect to be reconstructed up at the Villa, here in Los Angeles. A kind of a Roman pavement, a Roman-inspired pavement.

GASPAROTTO: [over Christiansen] Yeah, yeah, yes, yes.

CHRISTIANSEN: And you and I both know it’s very Lombardi.

GASPAROTTO: Very Lombardi, the—

CHRISTIANSEN: [over Gasparotto] And the Lombardi were the great architects of the fifth—of late fifteenth century Venice, and this is the kind of rich marble encrustation they loved, derived from Byzantine practice. But it’s this incredible enclosure with a wild, deteriorating, rocky landscape in the background. And then in the far distance, you finally get to this beautiful green. And always with Bellini, there is a castle fortress on the peak of the hill.

GASPAROTTO: On the peak of the hill, yes.

CHRISTIANSEN: And this is provocative. And here, it’s almost dead center, that.

GASPAROTTO: Mm-hm, mm-hm, mm-hm.

CHRISTIANSEN: So you have a contrast between, once again, a castle fortress in the foreground, and a paradisiacal serene enclosure in the foreground.

GASPAROTTO: [over Christiansen] With a very curious, you know, group of saints, which we can recognize, we can guess. Because I think here on the right, there are these two semi-clad figures. One is clearly Saint Sebastian, pierced by two arrows. One is a nude saint, an old man, tanned, probably Saint Job, who was very popular, a popular a saint in Venice, you know?

CHRISTIANSEN: [over Gasparotto] Important to remind people that in Venice, uniquely, Old Testament prophets were treated as saints. And there are churches dedicated to Job and to Moses.

GASPAROTTO: And to Moses, yes.

CHRISTIANSEN: And the—

GASPAROTTO: Yes. And on the other side of this beautiful terrace, this beautiful enclosed space, there is obviously, on a throne, on a high throne, sort of an antique decorated with antique reliefs of the Virgin, with the hands joined in prayer flanked by two female figures, which we are not able to recognize. But they are saints, female saints. And then immediately out of this enclosed space, we see two other saints. One is—I think it’s Paul. I think you agree [CHRISTIANSEN: That’s right.] that probably this was iconographies by—it’s Paul. He has a long beard. And the other saint was discussed. I personally think it’s Saint Joseph, because he’s sort of lovingly— [CHRISTIANSEN: Protective.] protectively and lovingly gazing to the figures of the puti. In the center of the picture, one of them is sitting on a cushion. He is dressed and he’s holding an apple. He’s probably—I think it’s the Christ child. And the other three are holding and shaking the tree and picking up the apples.

CHRISTIANSEN: [over Gasparotto] Also because his mother Mary, on the throne, is clearly looking at—

GASPAROTTO: It’s clear. To me, it’s a sort of a sacred conversation rotated of ninety degrees. Instead of being frontal, it is rotated. And instead of being in an interior, it’s in an exterior. But there is something, I think, which it’s not totally clear. We don’t grab totally the meaning of the picture.

CHRISTIANSEN: So my guess, my thought is that it’s a picture about access and entrance. Because the gate to this enclosure is open. It’s guarded by Saint Paul. And he’s clearly just threatened a turbaned Muslim, who is not allowed access. And the question is, who has access to this paradisiacal garden? And so we’re back to that whole world of the voyage of life, the search for salvation, the search for meaning. And in the background in this rocky landscape, you then have this extraordinary assortment of figures. You know, you have a shepherd sitting in a grotto with a goat and with sheep. You have a figure who I think we can all—Saint Anthony.

GASPAROTTO: [over Christiansen] Saint Anthony.

CHRISTIANSEN: Who has walked down a path.

GASPAROTTO: Yes.

CHRISTIANSEN: He’s on the edge of the cliff, where there is a wall that’s fallen into ruin. There’s a cross set up; he’s past that. He’s walked out by a wattle fence. He’s now descending the stairs. And when he turns the corner, he’ll encounter a centaur. A figure from the Classical past.

GASPAROTTO: [over Christiansen] But I think this is in the golden legend, when Saint Anthony meets the centaur, and who indicates him the way to find Saint Paul.

CHRISTIANSEN: [over Gasparotto] Who he will have conversations with.

GASPAROTTO: [over Christiansen] So perhaps this is—I think I—I believe that perhaps the background is sort of the space of hermitage, the space, I don’t know, maybe of faith before—you know?

CHRISTIANSEN: It may be—I’ve always—this is a part that has actually engaged me each time I see this picture. As we’ve always said, what makes these pictures so haunting is that they don’t have a clear, closed program.

GASPAROTTO: Yes.

CHRISTIANSEN: They’re suggestive.

GASPAROTTO: Yes, yes.

CHRISTIANSEN: They’re suggestive. And this is what in the art historical literature, we call a poesia. They’re poetic. And as in all poetry, the visual language is meant to suggest associations.

So you have in the background, a figure driving a donkey. He’s followed by another figure with a stick on his shoulder, and there are two turbaned figures having conversation. But the wall that they’re standing in front of is completely dilapidated. And the wall behind the building is dilapidated. And so it’s a city that’s partly in ruin. Is this the Old Testament world?

GASPAROTTO: Uh-huh, mm.

CHRISTIANSEN: It certainly is not. Or is it just the deterioration of the city of man, despite the castle looking over it and despite the villa? And you know, the picture has suffered some. It’s not in the best condition.

GASPAROTTO: [over Christiansen] No, it’s not in pristine condition.

CHRISTIANSEN: [over Gasparotto] It still is magical. But the one—

GASPAROTTO: [over Christiansen] There is the reflections, for example, on the wall [CHRISTIANSEN: Exactly.] are wonderful.

CHRISTIANSEN: But I’ve always wondered, on that villa, you can see that there’s a loggia for people to sit out. But the area behind, I can’t tell whether the villa is falling into ruin, as well. That I’m just not certain of.

GASPAROTTO: In some—

CHRISTIANSEN: [over Gasparotto] So these are puzzles. So these become incredibly puzzling things.

GASPAROTTO: [over Christiansen] Yeah, In some way, this painting is even more a painting for connoisseurs. [CHRISTIANSEN: Absolutely.] In this sense, it’s already pointing toward Giorgione, [CHRISTIANSEN: That’s right. That’s right, that’s right, that’s right.] toward the future of Venetian painting. It’s where Bellini meets Giorgione, in this sense of creating a picture which is a sort of a puzzle, which is for cultivated people, [CHRISTIANSEN: That’s right.] who were able to detect these complex meanings.

CHRISTIANSEN: [over Gasparotto] Absolutely. Now, on a simple level of where Bellini begins, where he ends, in the exhibition, you can start with that early crucifixion that we looked at, with the background of Netherlandish inspiration, with the way the river is shown there, and then the way the body of water is shown here, with this wonderful mirror-like surface, the reflections, and an atmospheric quality.

GASPAROTTO: Yeah, yeah.

CHRISTIANSEN: [over Gasparotto] An incredible atmospheric quality, I think.

CUNO: Christ Blessing, circa 1500, from the Kimbell Art Museum measures about 23 by 18 inches. It depicts an almost ethereal scene of Christ after having risen from the tomb.

CHRISTIANSEN: This is one of my favorite pictures. This picture is transporting.

GASPAROTTO: …because here, the figure is protagonist. [CHRISTIANSEN: Yeah, yeah.] It’s looking at us, it’s occupying almost the entire space of the panel. And it’s frontal, so it’s very engaging. It’s very close to us, in some way, like in the crucifixion. [CHRISTIANSEN: That’s right.] In Vincenza the Christ is present.

CHRISTIANSEN: Yeah. But you know, it also has a hieratic quality. And you recognize immediately that this stretches all the way back to Byzantine prototypes in the way it looks. But transposed into a beautiful, delicate, soft, sfumato, to use a Leonardo [GASPAROTTO: Sfumato, yeah.] term. A presence of a physical body. And the light in this. This is, I think, one of the places where people can appreciate the beauty of his sense of light. The hand is raised up in front of the body in an action of blessing. And there’s a delicate shadow that falls across his breast.

GASPAROTTO: [over Christiansen] On the chest, yes.

CHRISTIANSEN: It is spectacular.

GASPAROTTO: It’s spectacular.

CHRISTIANSEN: And—

GASPAROTTO: It’s a sort of a modern icon. [CHRISTIANSEN: Exactly. Yeah, absolutely.] It’s the recreation, it’s the linear recreation of the Byzantine icon, [CHRISTIANSEN: Absolutely.] in a modern way, in some way.

CHRISTIANSEN: [over Gasparotto] Absolutely. And then behind him—he’s up close to the front, just as— just as the Vicenza crucifixion is up close to the front. We have a little opening to the sides. Two rabbits nuzzling their noses. This is clearly symbolic.

GASPAROTTO: I think these are symbolic. I agree with you, yes.

CHRISTIANSEN: [over Gasparotto] And this is the resurrection.

GASPAROTTO: This is the resurrection, this is—

CHRISTIANSEN: [over Gasparotto] Because of the famous quality of rabbits to breed and—[GASPAROTTO: Yes. Yes.] But then behind, you have this extraordinary sequence of landscapes. On the left, is the world of everyday life, where a shepherd is watching his sheep in the fields. And on the right, we once again have that pilgrimage. There’s a church in the background with a fabulous church tower.

GASPAROTTO: [over Christiansen] It clearly is model of a village, you know? [he chuckles]

CHRISTIANSEN: [over Gasparotto] Village. Absolutely. The kind of place you’re from.

GASPAROTTO: Yes.

CHRISTIANSEN: And then the path that swings around and you see the three Marys making their way to the tomb on Easter morning. And then you realize that this extraordinary dawn—and the sun is just below the horizon, so that the undersides of the clouds are all illuminated with a golden light that turns gradually pink and violet as you move up. It’s extraordinary.

GASPAROTTO: [over Christiansen] To me, this is the most [CHRISTIANSEN: Wow! Wow!] moving image of [CHRISTIANSEN: It’s an amazing—] a dawn. It’s a real dawn, [CHRISTIANSEN: Yeah, yeah.] instead of—and one of the first, I think, [CHRISTIANSEN: Yeah.] in Italian art, probably, yeah.

CHRISTIANSEN: [over Gasparotto] Absolutely. Yeah, yeah. Let’s face it, throughout all these pictures, regardless of subject—it can be the tragedy of the crucifixion, it can be the mysterious allegory from the Uffizi, or it can be this resurrection—there’s a serenity.

GASPAROTTO: Yes.

CHRISTIANSEN: And I think it’s that [GASPAROTTO: Yeah.] serenity that was the key to his enormous success. They were pictures that are meant for meditation, for standing in front of, for projecting your own thoughts on them. And then also for extracting from them for yourself, this extraordinarily peaceful, quietude. In that sense—

GASPAROTTO: [over Christiansen] And I think this quality is still able to work, [CHRISTIANSEN: Absolutely.] I think, because I see here, the public, the visitors, they are taken by these images. They are looking very close. They are images that are really moving, still today.

CHRISTIANSEN: They have that sort of meditative quality that in twentieth century art, we get in Rothko. But they have a specific thereness. You know, there’s a specific place, a specific time of day, a specific architecture, a specific landscape. That’s the big difference. But they do have that same quality of meditative serenity, and they invite prolonged viewing. Prolonged and very intense [GASPAROTTO: Detailed, intense.] detail, focused viewing [GASPAROTTO: Yes, focused viewing.]

You know, one of the most beautiful things for me is the combination of the raised hand with the bent fingers, set next to the barren branches of the tree, in which there’s a bird perched, against the clouds colored by the dawn light.

GASPAROTTO: Yeah.

CHRISTIANSEN: And just those three things—death, resurrection, and the life of the world, [GASPAROTTO: And the life of the world.]—are re-illuminated by the sun. It’s really extraordinary.

CUNO: In his life of Bellini, Giorgio Vasari wrote, “Finally, having lived ninety years, Giovanni passed from this life, overcome by old age, leaving an eternal memorial of his name in the works that he had made both in his native city of Venice and abroad…. [Men] sought to honor him when dead with sonnets and epigrams, even as he, when alive, had honored both himself and his country.”

Bellini was among the greatest painters of the Renaissance. And it was a stimulating pleasure to me to listen to two curators talk about his work with erudition and passion. Later that day, Davide and Keith discussed three paintings by the late sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century Italian painter known as Caravaggio. We’ll share that conversation in two weeks. Thanks for listening.

Our theme music comes from “The Dharma at Big Sur,” composed by John Adams for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003. It is licensed with permission from Hendon Music. Look for new episodes of Art and Ideas every other Wednesday. Subscribe on Apple Podcasts or Google Play Music. For photos, transcripts, and other resources, visit getty.edu/podcasts. Thanks for listening.

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

KEITH CHRISTIANSEN: Throughout all these pictures, regardless of subject, there’s a serenity. ...

Music Credits

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.