DaShell Hart and Barbara Lewis of the Bodacious Buggerrilla in a scene from “Killer Joe”

In South-Central in the ‘60s and ‘70s, everybody knew Bodacious Buggerrilla. The street theater group staged shocking and hilarious consciousness-raising skits at schools, churches, cafes, prisons, even Laundromats.

Members of the group spoke with us before their recent appearance at the Getty Center as part of the just-concluded Pacific Standard Time Performance and Public Art Festival. They’d just finished a dress rehearsal for the evening’s reprise of “Killer Joe,” a comical vignette about a shameless pimp who loses his Cadillac, cash, and chicks and is shamed home to his Bible-toting mother.

How do you define Bodacious Buggerrilla?

Ed Bereal: Bad motherf****rs.

We’re a guerrilla theater group involved in social and political critique.

Bodacious Buggerrilla got started out of a UC Riverside black studies class. Tell us how.

Larry Broussard: Me and Ed got to talking about we could be effective and spread truth. Young people—young men especially—were getting killed. As a result, Ed came up with the idea of this theater group. We would get together and start thinking about ways we could influence young folks to get an education and do the right thing.

Each skit has something to tell you, even “Killer Joe.” In the black community, Killer Joe was revered by young people. He’s all about the illusion of wealth, of status and all of that stuff. It ain’t real. It can disappear in an instant.

Tendai Jordan: You can liken that to people who want to be rap stars now.

Barbara Lewis: You can liken it to reality shows.

Alyce Smith-Cooper: And underneath all of it is a lot of pain: “How can we keep our brothers from getting killed?” We were expressing our pain about not knowing what to do and very often bringing the humor, because that’s often what comes out of pain.

Larry Broussard, DaShell Hart, Ed Bereal (in pig mask), and Bobby Farlice in “Killer Joe”

Did a skit like “Killer Joe” have to come out of a black studies class? Could it have come out of an art history class, a performance art class?

Alyce Smith-Cooper: If could have been a film class, a nursing class. It had to be people with the same compassionate edge who wanted to see a change.

Ed Bereal: We could probably do a “Killer Joe” mechanics class.

Bobby Farlice: The ‘60s was the first time we were really allowed to explore ourselves and research our histories…it was a rich time, because everything was new and we hadn’t done this before.

Larry Broussard: We had to take it to the street. It had to go to the people. This couldn’t be done in nice theaters, this had to be done on the street, in the fields. We took it to the street because that’s where the people who were getting killed were.

Killer Joe loses it all.

How does it feel to get back together after 40 years?

Bobby Farlice: It’s a very interesting feeling. We’re all on the same page. We still hold the same truths, and we still hold the same beliefs and convictions.

Alyce Smith-Cooper: The compassion we had [for one another and the audience], I felt that instantly again. We worked together like family. In three days, we got the magic back again.

Ed Bereal: We mess with each other a lot. It’s like family. What happens on stage is just a reflection of the way we’ve interacted with one another. There was a magic in this group, a fantastic magic.

What’s the group about today?

Bobby Farlice: We’re a reflection of what’s going on in the world today. What spawned us in the ‘60s—the conditions that existed politically and socially—are coming back.

What conditions are coming back today?

Larry Broussard: It’s the 99% versus the 1%.

Bobby Farlice: In the last year, I’ve never seen as many people beat on by the police as since the ‘60s, the civil rights movement and the anti-war movement.

Alyce Smith-Cooper: It’s still about race, it’s still about class. It’s still about economics. It’s still about the elite versus those who don’t have as much, and their intention to keep it that way. Some of the dynamics have changed: now we have an African American president, and I didn’t even think about that in the ‘60s. But many of the other dynamics are still there.

Bodacious Buggerrilla member DaShell Hart as Killer Joe

Do you relate at all to what the Occupy movement has been doing?

Larry Broussard: Both are protests. Our form of protest is to leave you with some degree of education, some degree of reality about your condition and what you can do about it. When you know, you can act. When you don’t know, you can’t act.

We bring a universal truth, a universal teaching about hate, about violence, about what you do when you find yourself in that position.

Ed Bereal: We were talking to a very specific audience [in the ‘60s and ‘70s]. We understood that audience, because we were them and they were us. In many ways we were their voice.

We used humor a lot even though the subject matter was dead serious. We’d often do it in a satiric way because our audience got it, seemed to like it better, and was more open to us if the satire or the humor was there.

What makes humor so effective?

Ed Bereal: If you’re laughing, your mouth is open. If your mouth is open, somebody can put something in it. (Laughter.)

Barbara Lewis: It’s the spoonful of sugar that helps the medicine go down.

Tendai Jordan: And you can relate to it. The whole idea is activism, but we weren’t just on stage. We were part of the audience, and the audience was part of our performances.

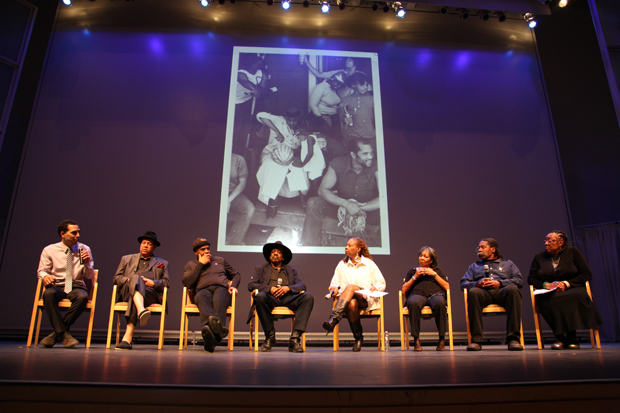

Bodacious Buggerilla on stage for the panel discussion with curator Malik Gaines

One of Bodacious Buggerrilla’s goals is to uplift people. How do you do that?

Larry Broussard: They see themselves in some of the stuff we do. There’s a story Ed tells about a guy who came in after we did “Killer Joe” and the whole audience looked at him and knew. They laughed the poor guy out of the place.

Ed Bereal: He came in dressed like the character we had just ridiculed! The whole place was hollering, and he had no idea.

Tendai Jordan: About being uplifting, we had discussions about how we ended any vignette so that it would be uplifting and leave the individual knowing that there is hope, that there is action they can take, that they have some power in their life.

Larry Broussard: The thing with “Killer Joe” that’s important is that you can always go home. And you’re going to have to go home when you’re butt naked with nothing. You’re going to have to go home to the very roots, go back and get it right.

Tendai Jordan: That’s the message: you are better than that.

Text of this post © J. Paul Getty Trust. All rights reserved.

The woman in the blond wig was actually Barbara Lewis. The photos were great as was the reporting of the dialog. Thank you for preserving these precious moments of reunion.

Alyce Smith Cooper

Hi Alyce, It’s great to hear from you here on the blog! It was such a pleasure meeting you and hearing your thoughts. We’ve updated the image caption — thanks very much for the correction. -Annelisa/Iris editor

Hi Annelisa, The blog has served more than one purpose. It got me back in touch with a beloved family member who works at the Getty who I did not get the chance to inform of the performance. The good part is that she now knows that I’m back to acting again. Maybe she and other family will get to San Diego to see GOD’S TROMBONES before it closes on 3/11. Anyway, it was an unexpected boon. Alyce

It was a real thrill to see pictures of all that gang again – they were truly an inspiration and a great team

That’s great to hear Cadena!