Art history, like most other professions, relies on acronyms. CIHA refers to the International Committee for the History of Art, which is one of the oldest organizations in the profession, founded in 1930. I recently attended CIHA’s 33rd Congress in Nuremberg, Germany, presenting my own research in a session devoted to the art market, and representing the Getty Foundation, since we gave a grant to allow art historians from the developing world to attend the conference.

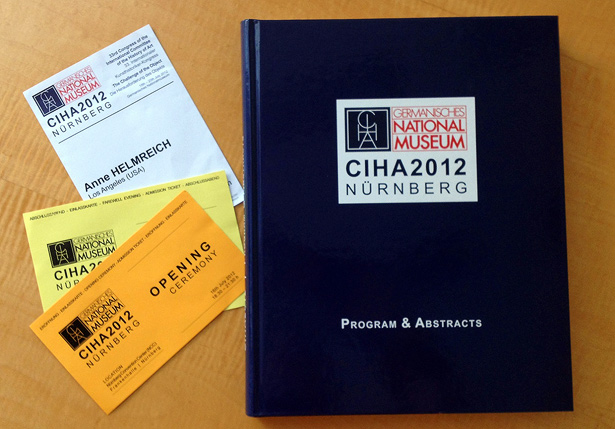

Held every four years, the CIHA Congress could be called the Olympics of art history. Here, the hefty program and my badge and tickets.

With the summer games just about to begin in London, I couldn’t help but notice parallels between CIHA and the Olympics. When CIHA was established, a key purpose was to organize a congress every three years, a period now extended to every four years. The affair is short but jam-packed with diverse events (alas, no medals). Each day of CIHA is consumed with scholarly presentations (organized around preselected themes) as well as meetings and museum visits. The conference abstracts fill an inch-thick book; another program is needed to list the posters and abstracts of the postgraduates.

Like the Olympics, much fanfare marks the opening and closing ceremonies. This year the host for the event, the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, invited the Federal Minister of Education and Research, Dr. Annette Schavan, to deliver the opening speech. To put this in perspective, can you imagine the U.S. Secretary of Education attending an art history conference?

Farewell addresses were given by the Lord Mayor of Nuremberg; the Australian ambassador to Germany; the Bavarian State Minister of Sciences, Research, and the Arts; and the director of the Institute for Hans Arts Study at Peking University (Beijing will host the next congress in 2016). It is amazing to think of an art history conference receiving so much attention. In fact, the session in which I participated, “The Object Transformed by the Art Market,” was covered by a reporter from the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, a prominent international paper. This level of commitment was echoed in the conference itself, where one felt truly excited about the future of art history and that much was at stake. Senior scholars helped to frame the debates, and junior scholars showed the future of the discipline.

And finally, like Olympic athletes, CIHA attendees come from all around the world. For those traveling from less affluent parts of the globe, this presents problems—both for the participants and for the conference, because the future strength of art history will depend on how effectively the discipline can accommodate different points of view from scholars around the world. For this reason the Getty Foundation provided a professional development grant to the congress host, the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, to offer travel support for participants from underrepresented countries. As a result more than 70 scholars from all over the world—from Africa (Benin, Cameroon, Nigeria, South Africa), China, Central and Eastern Europe (including the Czech Republic, Croatia, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Ukraine, and Serbia), and Central and South America (Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, and Colombia)—attended the conference.

Art historian Elena O’Neill at the CIHA Congress, presenting a poster session on her dissertation research.

Many of these scholars, like me, had never been to CIHA before and found the opportunity to share their research and learn from others completely exhilarating. They felt that what they had to say mattered and would be heard by the field at large. I was particularly struck by a Ph.D. student from Brazil, Elena O’Neill, who stood proudly by her poster describing her dissertation in progress. “Being able to present my research at CIHA was important for my career,” said O’Neill. “I had the opportunity to attend lectures of scholars from many parts of the world, with different approaches, on various topics, arguing about their research.”

Now after the close of our scholarly Olympics, the presentations and conversations from CIHA are continuing to resonate here at the Getty as we think about how to practice and support art history in our new globalized age. And when we gather four years from now for the next congress, we are optimistic that our discipline will be stronger than ever before.

Comments on this post are now closed.