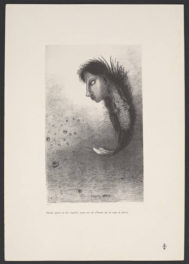

Bust of an Aztec Priestess, Jean Massard the Elder. Lithograph in Alexander von Humboldt, Vues des Cordillères, et monumens des peuples indigènes de l’Amérique (Paris, 1813), plate 1. The Getty Research Institute, 85-B1535

Throughout 2013, the Getty community participated in a rotation-curation experiment using the Getty Iris, Twitter, and Facebook. Each week a new staff member took the helm of our social media to chat with you directly and share a passion for a specific topic—from museum education to Renaissance art to web development. Getty Voices concluded in February 2014.—Ed.

In 1813, Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859), the renowned naturalist and explorer of Central and South America, published a monumental volume describing peoples, landscapes, and antiquities he encountered during his journeys. This work, Vues des Cordillères, et monumens des peuples indigènes de l’Amérique, includes a full-page lithograph of an Aztec statue. For a number of years, this statue (now in the British Museum) was in the possession of Guillermo Dupaix, an antiquarian appointed by the King of New Spain to explore and document the ruins of ancient Mesoamerican civilizations. While on his own scientific expedition through New Spain, Humboldt was able to study Dupaix’s statue.

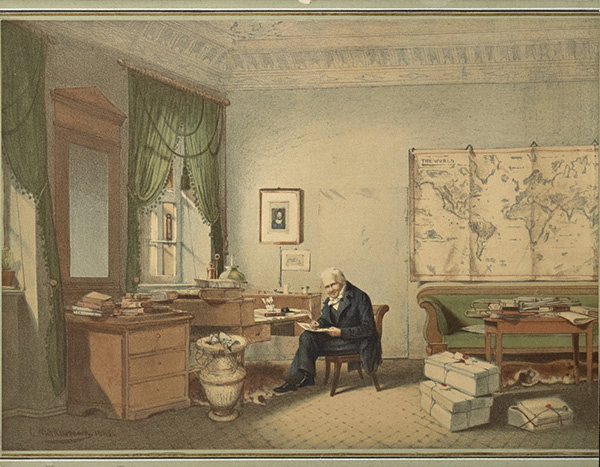

Alexander von Humboldt in his study, 1848, anonymous after Eduard Hildebrandt. Color lithograph, 10 1/16 x 14 in. The Getty Research Institute, 2013.PR.38

Along with the illustration, Humboldt describes the statue at length. He generically identifies the Aztec sculpture as a “water priestess,” known today as an image of the water goddess Chalchiuhtlicue. What’s most fascinating about his analysis is the way he describes the statue’s stylistic features. He relates them to forms adopted by ancient cultures known to him. In particular, he compares this Aztec statue to the faces carved on the tops of columns at the temple of Hathor at the ancient Egyptian site of Dendera.

Humboldt writes of the statue that it “presents the greatest likeness to the grooved drapery around the heads seen on the capitals of the columns at Tentryris [Dendera], as can be proved by looking at the accurate drawings that Denon has given in his Voyage en Egypte.”

![gri_84_b2386_v2_344327ds_[1]2](http://blogs.getty.edu/iris/files/2014/01/gri_84_b2386_v2_344327ds_12.jpg?x45884)

Temple of Hathor at Denderah [Tentyris], Elevation (detail), Louis Pierre Baltard after Vivant Denon. Engraving in Voyage dans la Basse et la Haute Égypte, pendant les campagnes du général Bonaparte (Paris, 1802), pl. 39. The Getty Research Institute, 84-B2386

Why would Alexander von Humboldt, traveling through the mountains and jungles of the Americas, think to liken an Aztec statue to the remains of a sanctuary over 7,000 miles away, on the banks of the Nile? The first part of the answer to this question is “Egyptomania,” the widespread cultural fascination with everything having to do with ancient Egypt.

Egyptomania has a long history in Western culture. The ancient Romans fetishized and emulated the art and religions of Egypt for centuries. Egyptian signs and symbols have been implemented by nearly every mystic or occult movement originating in Europe since the Renaissance. And even today there are signs of Egypt all around us—just take a trip down to Hollywood to the Egyptian Theatre!

At no point was Egyptomania more feverish than during the 19th century. Egyptomania exploded following Napoleon Bonaparte’s campaign in Egypt from 1798 to 1801, which failed to conquer the region politically but succeeded in encyclopaedically documenting its ancient past, contemporary culture, and natural history. The first work published about the expedition was an illustrated travel narrative by Vivant Denon (1747–1825), one of the most adventurous members of the scientific civilian group that accompanied Napoleon’s army. Denon paid special attention to Dendera in his Voyage en Egypte, which was reprinted and translated as it became a best-seller.

After Denon’s publication, the faces on the columns at Dendera began to appear everywhere. They were copied and published in book after book on Egypt, used as models for theater sets, and replicated on everything from decorative vases to clocks. Perhaps they are most beautifully seen in the epic publication sponsored by Napoleon himself, the massive, multi-volume Description de l’Égypte…, a copy of which is on view in the exhibition Connecting Seas. In the first decade of the 1800s, when Humboldt wrote his work on ancient Mexico, Dendera was in the mind’s eye of every intellectual in Europe.

Temple of Hathor at Dendera [Tentyris], Interior View, (detail), François-Noël Sellier after Jean-Baptiste Prosper Jollois and René Edouard de Villiers du Terrage. Etching and engraving in Description de l’Égypte; ou, Recueil des observations et des recherches qui ont été faites en Égypt pendant l’expédition de l’armée française / publié sur les ordres de Sa Majesté l’empereur Napoléon le Grand: Antiquités, Planches, vol. 4 (Paris, 1817), pl. 30. The Getty Research Institute, 83-B7948 c. 1

The Egyptomania brought on by Napoleon’s expedition affected the interpretation of Mesoamerican antiquities broadly—Humboldt’s Egypt-inflected vision was no isolated case. Campaigns of exploration into the Americas were modeled after the endeavors of Vivant Denon and his fellow savants in Egypt, and the famous monuments of the Yucatan, like those found at Uxmal and Chichén Itzá, were compared to Egyptian pyramids in early published descriptions. Some of the authors even proposed the idea that in the very distant past, the ancient Egyptians themselves had constructed these “lost” cities in the jungle.

Castle at Tulúm, 1844, Andrew Picken after Fredrick Catherwood. Color lithograph in Views of ancient monuments in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatan (London, 1844), plate 23. 29 15/16 x 21 7/16 in. The Getty Research Institute, 84-B8523

This story is one of many featured in the “Expeditions and Explorations” section of Connecting Seas at the Getty Research Institute, which presents some of the seminal volumes created in the first half of the 19th century. These books show the first steps by Europeans, some two centuries ago, toward serious scholarship of ancient cultures around the world.

Comments on this post are now closed.