In early modern Europe, banquets became works of art. Table with 100 Settings. Engraving, 8 1/3 x 11 7/9 in. In Juan de la Mata, Arte de reposteria… (Madrid: Antonio Marin, 1747), pl. 10. The Getty Research Institute

The spectacle of putting on a great show with food serving as props is a tradition dating back to at least medieval times. Think of a court jester jumping into a giant custard pie, splattering all the illustrious guests within range. Or the lines from the nursery rhyme “Sing a Song of Sixpence” in which live birds are released from a baked pie—an actual occurrence at some feasts.

Banquets allowed the ruling aristocracy to show off their wealth and their hired talent; it was essential to employ a chef who could produce eye-catching edible monuments made of sugar, many of which reached as tall as a person.

From a Hodgepodge to Sugary Sweet

Before the rise of sugar plantations, edible monuments were sculpted from a hodgepodge of more or less consumable ingredients. They might be constructed of long-lasting foods such as cheeses and hams, and interspersed with glittering dishes of silver and gold. Colorful vegetables and fruits would be added, particularly those imported from foreign lands.

Sugar transformed the game. The sweet substance had, of course, been around for centuries, but it was rare and expensive, used more as a seasoning like salt than as an independent ingredient. With the discovery of the New World, the role of sugar changed. By the end of the 16th century, cones of solid refined sugar were cheap, widely available, and convenient for grating in the kitchen.

Processing raw sugarcane into solid sugar loaves. The Invention of Sugar Refinery, Jan Collaert I after Jan van der Straet, called Stradanus. Engraving, 10 5/8 x 7 7/8 in. In New Inventions of Modern Times (Nova Reperta…) (Antwerp: Philips Galle, ca. 1600), pl. 13. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 49.95.870(4). The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1949. Source: www.metmuseum.org

Pastillage

The cheap cost of sugar led to the creation of pastillage, a pliable, long-lasting paste made from powdered sugar and gum arabic, the edible sap of the acacia tree. Pastillage survives well in the open air, unlike a paste made of pure sugar, which dissolves in humidity within hours. With the inclusion of gum arabic as cement, chefs could attempt even more daring structures. Pastillage is still widely used today; it can be delicately or brightly colored, modeled or rolled thinly, and shaped at will like pottery clay.

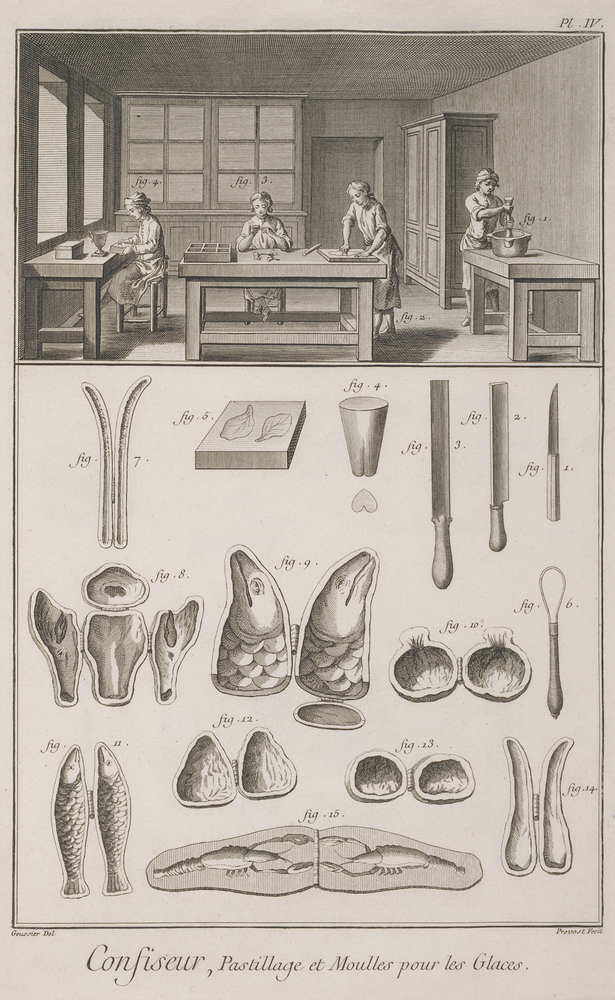

Working with pastillage is a time-consuming specialty. Candy Making, and Ice Molds. Etching, 13 7/8 × 8 7/8 in. In Denis Diderot, Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné: Recueil de planches, vol. 3 (Paris: Chez Briasson, 1765), pl. 4–1. The Getty Research Institute, 84-B31322

The End of the Feast

What became of edible monuments at the end of the event? In 1688, at a feast hosted by England’s special ambassador Lord Castlemaine to honor Pope Innocent XI in Rome, Swiss guards were hired to protect the exhibits set on the banquet table. Not all hosts took such a protective stance. At some feasts, the creations were handed out to honored guests, who devoured them after returning home. On more public occasions, the general populace was allowed inside to view the display. It was not uncommon, after the formal viewing, for the crowd to be let loose to demolish the monuments. It was all part of the show.

To this day, a feast is not complete without a sugary, edible monument. Think of our tiered wedding cakes or elaborate birthday cakes. In a top restaurant, even a simple dessert can be art, with blown and pulled sugar set in fantastic starbursts of colors and shapes, evoking the architecture of Frank Gehry like a miniature Walt Disney Concert Hall on a plate. A monument gone mad you might think. But isn’t that the whole point?

Sugar sculptures became as elaborate as Baroque architecture. Surtouts and a Geometric Table Plan (sugar sculpture designs at top, table placement below), 1751, Jean-Charles François after Nicolas-Gabriel Dupuis. Etching, 33.8 x 21.8 cm. In Sieur Gilliers, Le cannameliste francais…, pl. 11. The Getty Research Institute, 85-B5272

Good piece…..I enjoyed. I have a friend here who makes sugar cones for 18th c. Re-enactors….I am also one. I will send this to her.

So glad you enjoyed, Abby. Such wonderful and articulate work, very impressive.