Serie Reyes y Profetas de Israel, Salomó, ca. 1764, Marcos Zapata. Oil on panel. Cuzco, Prelatura de Humahuaca. Academia Nacional de Bellas Artes. Photo: Diego Ortiz Mujica for Fundación Taller Restauro de Arte (TAREA)

Art history is sometimes imagined as a discipline of solitary scholars, not unlike King Solomon as depicted in this Viceregal painting by Marcos Zapata: alone in a study, poring over texts, and waiting for the moment of inspiration (perhaps divine?) to strike. But a group of international scholars recently hosted at the Getty Center by the Foundation demonstrated that this is indeed a stereotype, and one that may no longer have much relevance.

Materiality between Art, Science, and Culture in the Viceroyalities (16th–18th Centuries) is a series of research seminars organized by the Universidad Nacional de San Martín in Argentina that is bringing together scholars to examine the artistic materials—everything from wood to feathers to animals and insects ground up to make pigment—used during this period in Latin America, what made them unique, and what they can tell us about the history of art and cultural exchange.

Cross‑section of the pictorial layer of the painting shown above (from the cloth of Solomon), in which a mixture of indigo and the mineral orpiment has been identified. Photo: Diego Ortiz Mujica para Fundacion Taller Restauro de Arte (TAREA)

The project is supported by a grant from the Foundation as part of its Connecting Art Histories initiative, which enables scholars from different parts of the globe to come together to exchange ideas and create new intellectual networks.

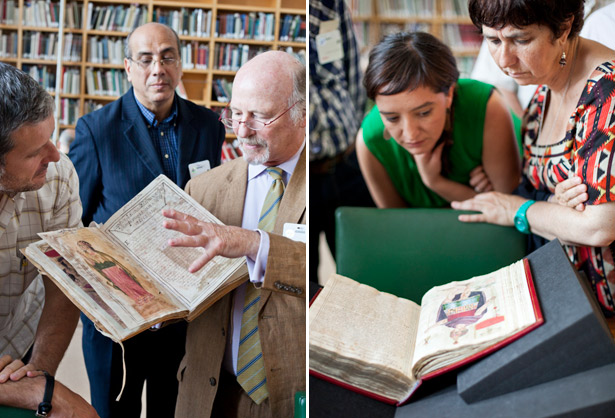

The Materiality group visiting the Getty Center as part of a Foundation grant

“This project has the aim of reconsidering Spanish American Colonial art history from a specific point of view: to link objects and works of art produced within that time with their material dimension and cultural practices,” project director Gabriela Siracusano, a leading art historian based at the Universidad San Martín and CONICET in Argentina, told me. “In this attempt, interdisciplinary work is a must.”

The Materiality project team during their first meeting in Argentina, fall 2011

True to Siracusano’s mandate, the project team is as about as interdisciplinary as they come. The art historians, conservators, curators, and scientists—specializing in nanotechnology, organic chemistry, accelerator physics, and materials science—who form the team hail from Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Germany, Italy, Mexico, Peru, Spain, and the United States. The Getty grant will make it possible for all of these individuals to come together four times over the next few years for intensive research meetings.

Even more striking than the impressive list of countries and professions that the research team offers is the strength of their collaboration. “We all work together as equal partners,” Siracusano said. “It used to be that if you wanted to know about the material composition of an artwork, what this might say about its origins or patronage, we as art historians would just hand it over to the conservator or the chemist and that was that. We weren’t supposed to ask questions or interact. Now we have come to the point where we inform each other’s work completely, and our research shows the benefits.”

Team members examine Martín de Murúa’s Historia general del Piru, 1616, an illustrated chronicle of Peru. (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XIII 16)

In many ways, this group demonstrates a powerful path for future research in art history. As Manuel Eduardo Espinosa Pesqueira, a doctor in materials science at the Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Nucleares (ININ) in Mexico, puts it, “it took about two decades of doing this work to gather momentum, adapting our tools and approaches in order to study works of art. But now we see it is working. Funding is more available, our students are finding jobs in this area, and we are very busy!”

With the research team only halfway through the project, there are certainly more exciting discoveries ahead. And we at the Foundation look forward to sharing these developments and others as Connecting Art Histories progresses.

Me gusta y me interesa,por eso quisiera tener mas comentarios de vuestras actividades.Desde ya los felicito.Un orgullo Argentino.

Dear Carmen,

Thank you for your comment! For more information on the project, I suggest you visit the website created by the research team:

http://materialityseminars-gettyunsam.blogspot.com.ar/

Katie Underwood, The Getty Foundation

Thoughtful comments , I am thankful for the specifics , Does anyone know if my assistant could get access to a fillable CA DTSC 1358 version to edit ?