See this GIF larger (3.7 MB) | See on Tumblr

Every tourist in Paris visits the Louvre and the Church of the Invalides. Most visitors also take time to trek 30 minutes by train to Versailles. What we see of these sites today is largely because of Louis XIV, who supported all three projects with a huge seemingly limitless budget—so much so, that the government’s not-so-limitless coffers were noticeably affected by the king’s profligacy.

The only building Louis constructed from the ground up was the Invalides, and the golden dome of its church still glitters with the kind of splendor that would have made the Sun King shine with pride. The complex of the Invalides, literally invalids, was built to house wounded soldiers who fought the king’s endless battles. Louis being Louis, he insisted that the church serve as something more than just a place of worship for his soldiers. It was to be an example of French glory, magnificence, and engineering.

The only building Louis constructed from the ground up was the Invalides, and the golden dome of its church still glitters with the kind of splendor that would have made the Sun King shine with pride. The complex of the Invalides, literally invalids, was built to house wounded soldiers who fought the king’s endless battles. Louis being Louis, he insisted that the church serve as something more than just a place of worship for his soldiers. It was to be an example of French glory, magnificence, and engineering.

Street view of the Hôtel national des Invalides. Photo: Adam Polselli on Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

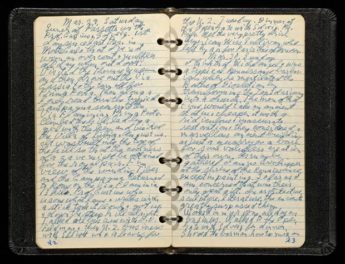

Given the complexity of the design, the height of the dome, and the richness of the material, planning turned out to be much more difficult than the architects had originally thought. With pressure from the king and his ministers to move forward, Jules-Hardouin Mansart, who took over as chief architect sometime after 1683, hit upon an idea to make large-scale prints of his designs for the church’s ground plans, elevations, and cupola. With these prints in hand, Mansart and his bosses and colleagues could discuss the design and start calculating costs. The façade we see in the print below went through some minor changes before the king signed off on the final design. (The king presided over the inauguration in 1706, only a short 36 years after the whole project was initiated!)

Facade of the Church of the Invalides, 1687, Pierre Lepautre after Jules Hardouin-Mansart. Etching and engraving from a bound volume of 14 prints (Bâtiments du roi, Paris, 1687). The Getty Research Institute, 1392-604

I have to admit, the first time I opened our volume, I was surprised to see just how large the prints are. For the façade, three separate copperplates were engraved by one of the foremost printmakers of the day, Pierre Lepautre; then three separate sheets had to be pulled from a printing press, dried, glued together, and carefully folded. Because this suite of 14 prints had a utilitarian purpose, rather than a strictly artistic one, it was never sold on the market. It’s extremely rare. We do know that some of the sets were probably given as gifts to diplomats or foreign courts. Our example at the Getty is probably one of these gift copies. Bound in red Moroccan leather stamped with gold borders, it was a luxurious gift meant to show off the new European center of architectural magnificence.

______

See the Sun King’s dome in the exhibition A Kingdom of Images: French Prints in the Age of Louis XIV, 1660–1715, on view at the Getty Research Institute June 16–September 6, 2015.

Comments on this post are now closed.