The Horses of Apollo, 1675, Etienne Picart after Gaspard Marsy and Balthazar Marsy. Etching and engraving in André Félibien, Description de la grotte de Versailles (Paris, 1676), pl. 17. The Getty Research Institute, 88-B13709

Viral media may seem like a 21st-century phenomenon, but French king Louis XIV made use of the concept long before tweets or memes. His technology of choice? Prints.

Viral media may seem like a 21st-century phenomenon, but French king Louis XIV made use of the concept long before tweets or memes. His technology of choice? Prints.

There was a hunger for images in the 16th and 17th centuries, which Louis XIV was more than happy to satisfy—with images of himself and his kingdom. The exhibition A Kingdom of Images: French Prints in the Age of Louis XIV, 1660–1715, on view June 16 to September 6, draws from the collections of the Getty Research Institute and the Bibliothèque nationale de France to showcase these original viral images.

Why Prints?

Prints have two key “viral” advantages, which Louis and his media-savvy advisors recognized:

Prints are reproducible. Etchings and engravings can be reproduced hundreds or even thousands of times from one original plate. Prints were created on a massive scale during Louis XIV’s long reign, amounting to hundreds of thousands of impressions.

Prints are shareable. Compared to paintings or sculptures, prints are economical to create and distribute. Louis XIV wanted his image to be seen by everyone, not just the courtiers at Versailles. Prints reached every corner of Europe and beyond.

The French Crown’s massive print campaign kicked off in 1670 with the establishment of the Cabinet du Roi, a vast printmaking enterprise dedicated to glorifying the king. The most renowned etchers and engravers were paid handsomely to record the glories of Louis’s reign, including his palaces, statues, paintings, tapestries, antique medals, and opulent festivals and events. These prints established Louis as a great patron of the arts and sciences, a heroic military figure, and a man of erudition and culture.

The prints of the Cabinet du Roi were luxuriously bound and bestowed as diplomatic gifts to foreign rulers. But the project quickly ran up extravagant expenses. To offset the cost, the volumes were sold on the market at affordable prices, extending Louis XIV’s image even further.

Procession of the King Accompanied by His Guards Crossing the Pont Neuf en Route to the Palace, ca. 1670, Jan van Huchtenburg after Adam Frans van der Meulen. Etching. The Getty Research Institute, 2012.PR.71

A Celebrity Exclusive

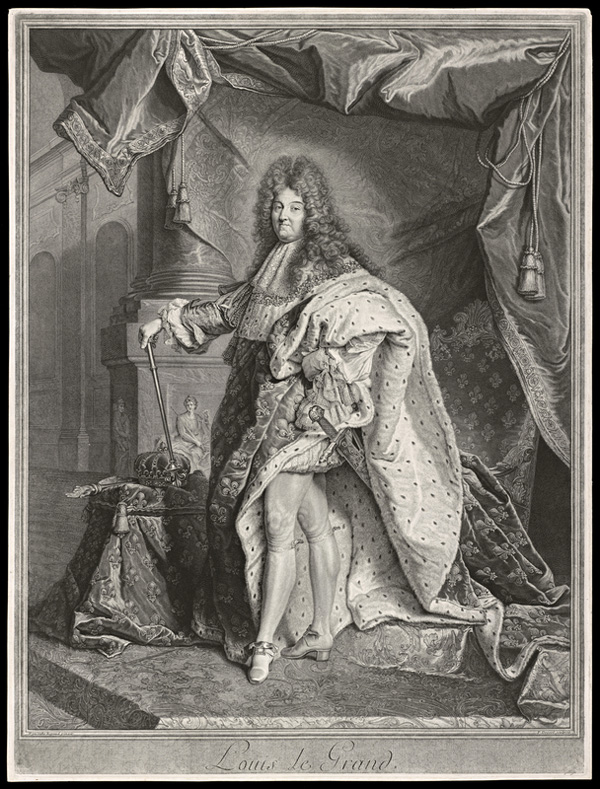

In an early version of the media exclusive, engravers and etchers not employed by the Crown were forbidden from creating images of Louis XIV’s palaces and art collections. The king’s face, however, was considered public property. In fact, “free and easy access to the prince” was considered a defining characteristic of the monarchy. His likeness appeared on all manner of printed materials, particularly almanacs created for the mass market.

Under Louis XIV’s watch, printmaking became a powerful tool capable of spreading political images with viral efficiency. Centuries later, the Sun King takes the title of the original tech-savvy celebrity.

Louis le Grand, 1714–15, Pierre Drevet after Hyacinthe Rigaud. Engraving. The Getty Research Institute, 2011.PR.13

_______

Louis XIV at the Getty is an occasional series illuminating the artistic legacy of Louis XIV on the 300th anniversary of his death.

Comments on this post are now closed.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks