“First, ever so lightly, I take a little flesh-colored pigment and add a bit of color to his face,” said Luther Gerlach as he glided his brush over an old photograph of a boy clutching a hat. “Then let’s add some browns to the shoes… It’s up to you, but I think a little bit of color goes a long way.”

Hand coloring—adding pigment to monochromatic photos—is the focus of several Artist-at-Work demonstrations being led by the photographer and instructor at the Getty Center this spring. These demos are free, drop-in programs that reveal the secrets of historical art-making techniques, from ancient mosaics to metalworking to photography. Luther’s demos offer the how-to’s of hand coloring, as well as a primer on authentic 19th-century cameras (from his extensive collection), developing processes, and glass negatives.

Luther Gerlach shows off some of his 19th-century cameras and equipment in the Museum Studios at the Getty Center

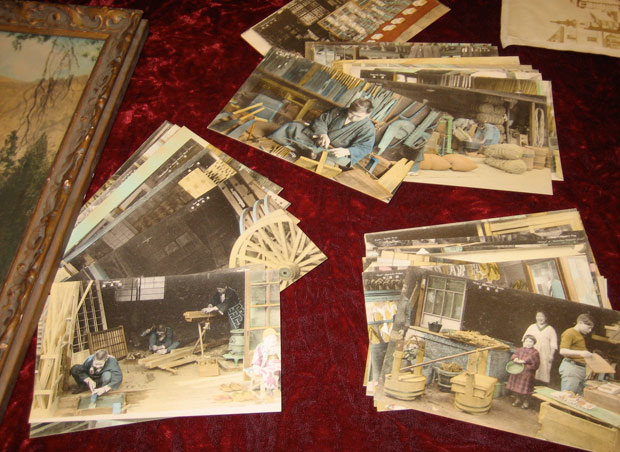

Hand coloring was extremely popular in the mid- to late 19th century, before color photography was invented. Tourists, especially, preferred souvenir prints and postcards that looked like real life. These novelties also fetched a healthy sum.

Felice Beato, the entrepreneurial global photographer whose work is currently on view in the Center for Photographs, saw the appeal—both artistic and commercial—of hand coloring. During his prolonged stay in Japan, from 1863 to 1884, he created that country’s first hand-colored photographs and albums.

He likely employed woodblock printers to have his images tinted and touched up with pigments and dyes. The subjects were shot in studios or outdoors, and many of the models made appearances in different photographs of daily and cultural life.

The photographs portray an assortment of scenes popular with Western audiences: people at work, in street scenes, modeling fashion, and taking trips. An 1868 album, digitized here, shows a fire master with a sea-foam-green helmet and a priest with a purple sash. Japanese women in traditional hairstyles and dress were captured as they applied pink makeup or had a Japanese-style shampoo.

Fire Master, Felice Beato, 1866–67. Hand-colored albumen silver print in Views of Japan (1868). 10 7/16 x 8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XO.613.26

Mode of Shampooing, Felice Beato, 1866–67. Hand-colored albumen silver print in Views of Japan, (1868), 7 1/16 x 11 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XO.613.33

Of all Beato’s hand-colored prints, it’s Koboto Santaro, the samurai warrior you may have seen on street banners around town, who makes the strongest fashion statement. The noble soldier serving Japan’s rulers sports a vivid armored costume of purple with a dash of orange and green. Now that was a stylish souvenir!

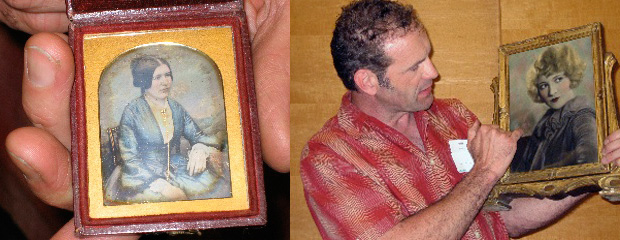

At the demo, Luther showed us hand-colored prints spanning nearly a century to contextualize Beato’s work on view upstairs. He also explored the proper—and imprudent—ways that pigments were applied to photos before the time of Kodachrome.

One example of superior artistry was a dolled-up photo of William Randolph Hearst’s mistress and silent film siren Marion Davies, who looks fetching in red lips and a blonde bob. Another star of the class was a tiny, 1840s daguerreotype of a lady sitting pretty with wisps of clouds in the background.

But Luther also held up a garish, mass-produced image of a Yosemite landscape crudely painted with blocks of color. “There can be real beauty in these, or they can look like a child colored over the lines,” he said.

The Artist-at-Work Demonstration is offered again on two more Sundays, April 3 and 17. It’s free; just drop by. And if you want to spend a whole day with hand coloring—and come away with your very own piece—you can join Luther for an all-day workshop coming up this Wednesday, March 16.

Comments on this post are now closed.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks