Initial A: Christ Wiping the Tears from the Eyes of the Saved, attributed to the Master of the Antiphonary of San Giovanni Fuorcivitas, about 1345–50. Tempera colors and gold leaf on parchment, 5 1/3 x 5 1/3 in (13.5 x 13.5 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 113, recto. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

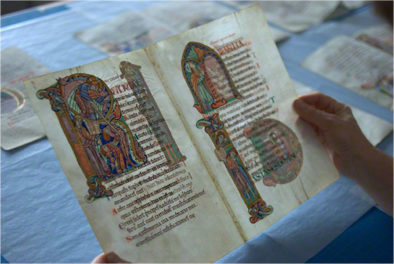

The Getty recently acquired a small but exquisite fourteenth-century painting by a highly skilled manuscript illuminator from Tuscany whose name has unfortunately not survived. The intimate scene of Christ wiping tears from the eyes of the saved at the Last Judgment was once part of a choir book and is currently on view in the exhibition Things Unseen: Vision, Belief, and Experience in Illuminated Manuscripts (until September 25, 2016).

This post will introduce readers to the challenges of studying “treasures of a lost art,” as one colleague brilliantly put it, and will make a case for christening an artistic personality whose identity has long been obscured in scholarship. A longer article was published in the Rivista di storia della miniatura, but I would like to use this forum to engage a wider readership of art lovers and scholars alike. Fellow scholars of paintings and the Middle Ages, I would love to hear your input on the identity of our anonymous illuminator—please share your thoughts in the comments.

Subject Matter, Musical Content, and Ecclesiastical Context

Standing in a voluminous garment with an orange and green cloak, Christ wipes away the tears of saints, who piously kneel before the savior. Saint Peter, in blue and yellow, and others stand behind the Lord. An angel holding a glass vial descends from elsewhere in heaven. The entire event is set within a pink letter A, which sprouts blue, green, and orange leaves. This type of illumination is referred to as a historiated initial because it contains a narrative scene. The overall size suggests that it was once part of a music manuscript, specifically a choir book.

Initial A: Christ Wiping the Tears from the Eyes of the Saved (detail), attributed to the Master of the Antiphonary of San Giovanni Fuorcivitas, about 1345–50. Tempera colors and gold leaf on parchment, 5 1/3 x 5 1/3 in (13.5 x 13.5 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 113, recto.

The letter A would have indicated the first letter of the first word of a chant, but when the initial arrived at the Getty, it was glued to a support that effectively obscured the text on the back. Based solely on the gestures, actions, and protagonists in the miniature, previous scholars interpreted the subject as Christ healing the blind, and I even suggested that the vial held by the angel might be a reference to contemporaneous fourteenth-century medicinal or alchemical practices related to sight or bodily health.

Thankfully, Getty manuscripts conservator Nancy Turner was able to skillfully remove most of the paper backing in order to allow the parchment (animal skin) to rest naturally. This treatment revealed the remaining textual fragments, allowing me to decode the chant and narrative scene.

Partial chant and musical staves (with fragments of a previous paper support), about 1345–50. Tempera colors and gold leaf on parchment, 5 1/3 x 5 1/3 in (13.5 x 13.5 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 113, verso. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Deciphering the above text required some close looking, but I was eventually able to transcribe the Latin words as, “[prio]ra tra[n]sierunt. // [Non esuri]ent neque si[tient]…” (the brackets indicate missing letters). Further digging revealed that the beginning of the chant is derived from Revelation 21:4, the last book of the Christian Bible, also known as Saint John’s Apocalypse. The verse begins, Absterget Deus omnem lacrimam ob oculis sanctorum, “God will wipe away every tear from the eyes of the saints…” and ends, quoniam priora transierunt, “For the first things have passed away.” (There are several great websites where you can enter partial text from a choir book in order to find the complete chant, so it was a fairly straightforward process). The chant continues with a portion of Revelation 7:16, Non esurient neque sitient, “They shall not hunger, nor shall they thirst.”

Initial A: Christ Wiping the Tears from the Eyes of the Saved (detail), attributed to the Master of the Antiphonary of San Giovanni Fuorcivitas, about 1345–50. Tempera colors and gold leaf on parchment, 5 1/3 x 5 1/3 in (13.5 x 13.5 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 113, recto. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

This specific chant indicated that the new acquisition was once part of a choir book known as an antiphonary (containing the chants of the Divine Office, or daily services attended primarily by the clergy), and this initial introduced a hymn sung for the Common of Martyrs.

The biblical passage and chant continue with Saint John’s vision in verse 9 as follows: “One of the seven angels who had the seven vials full of the seven last plagues came and said to me, ‘Come, I will show you the bride, the wife of the Lamb.’” The vial can therefore be interpreted as containing the last plagues that would be unleashed upon the earth in the final days before the Last Judgment. Based on this new discovery, Rheagan Martin, curator of Things Unseen, wrote the following label for the leaf’s display in the exhibition:

“While much of Saint John’s apocalyptic revelation was received visually, other portions of his text record the spoken word. This initial A reproduces part of that auditory revelation: a declaration that every tear will be wiped away from the eyes of the saints. In contrast to the visions of heavenly landscapes and boundless cosmic events described just before this utterance, the illuminator has focused on this spoken revelation to produce an intimate scene.”

Authorship and Anonymity at the Dawn of the Renaissance

Initial A: Christ Wiping the Tears from the Eyes of the Saved (detail), attributed to the Master of the Antiphonary of San Giovanni Fuorcivitas, about 1345–50. Tempera colors and gold leaf on parchment, 5 1/3 x 5 1/3 in (13.5 x 13.5 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 113, recto. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

What happened to the original manuscript and why wasn’t it signed? During the 18th and 19th centuries—as a result of numerous social, political, and religious events—illuminated manuscripts were often disbound, cut apart, and sold to collectors (we featured an exhibition on this topic a few years ago). It was far more economical to export small, lightweight pages from manuscripts, and collectors could easily fill scrapbooks and albums with the greatest hits of Italian Renaissance painting. It was likely during this period that the two-volume antiphonary fell victim to the “scissor men,” as these collector/dealer types are often called. When a manuscript leaf has been excised from its original context, it can be difficult to determine the full nature of the artistic collaboration that created it, since choir books were often the product of multiple artists working together. The surviving leaves, cuttings, and fragments of this particular manuscript had been tracked down by scholars for decades (more on that below), and yet numerous pieces to this puzzle have emerged even in the last year, including some exciting discoveries shared here for the first time.

Illuminated choir books were essential to the development of spirituality and painting in late medieval and Renaissance Italy. Until around 1400, however, far fewer artists signed their creations than in later periods, as the role of artists and the concept of individuality gained importance across Europe. The names of individuals who worked before 1400 in various media do in fact survive in a range of archival and literary texts (Dante Alighieri praised two manuscript illuminators whose artistic output is debated today) and at times through signatures (a thirteenth-century manuscript in the Getty collection was signed by one Jacobellus of Salerno, who called himself “little mouse,” or muriolus).

Yet even with these fortuitous surviving clues about artistic identity, art historians today contend with trying to piece together groups of stylistically similar objects to form an oeuvre or corpus for the innumerable personalities that would otherwise remain nameless. In fact, the same is required for understanding the artistic output of known artists, since again not every object bears a signature, nor do we always know the circumstances behind a work’s creation.

Christ and the Virgin Mary Enthroned, Attended by Seventeen Dominican Saints and Beati, Master of the Dominican Effigies, about 1335. Tempera and gold leaf on panel, 117.8 x 56 cm (46 3/8 x 22 1/16 in.). Florence, Museo e Chiostri Monumentali di Santa Maria Novella, Fondo Edifici di Culto, Ministero dell’Interno; Initial D: Saint George Venerated by Cardinal Stefaneschi and Saint George Slaying the Dragon, Master of the Codex of Saint George, about 1321-30. Tempera colors and gold leaf on parchment, 37.3 x 26.3 cm (14 11/16 x 10 3/8 in.). Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Archivio di San Pietro (C 129), fol. 85

Art historians traditionally ascribe identities to these unknown “masters,” often naming them after a work of the highest quality (a magnum opus) that exemplifies the so-called “hand” of an artist or workshop. The enigmatic Master of the Dominican Effigies, for example, is named after a panel from about 1335 in the Church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence showing Christ and the Virgin Mary Enthroned, Attended by Seventeen Dominican Saints and Beati and the contemporaneous Master of the Codex of Saint George is assigned an oeuvre that hinges on a Missal (liturgical manuscript used during Mass) commissioned by Cardinal Giacomo Stefaneschi that contains a text written by the patron on “The Miracles and Martyrdom of Saint George.” Both of these artists worked as panel painters and manuscript illuminators, often collaborating with the same shops on projects for the same patrons.

For over one hundred years, scholars have grappled with determining the artistic geography of the Getty’s new acquisition and with that of a group of leaves, cuttings, and fragments that are thought to have once been part of the same two-volume antiphonary—see the table at the end of this post for a list of the twenty-six surviving parts of this choir book set, including several that I have recently tracked down. Art historians generally agree that this artist or workshop was active in the first half of the fourteenth century in central Italy, but opinions on the precise geographic origins range from Bologna, Pisa, and Siena to Florence and even Umbria. Associations have been suggested with the Master of Saint Cecilia, Maestro Daddesco, Niccolò di Ser Sozzo, and Pacino di Bonaguida.

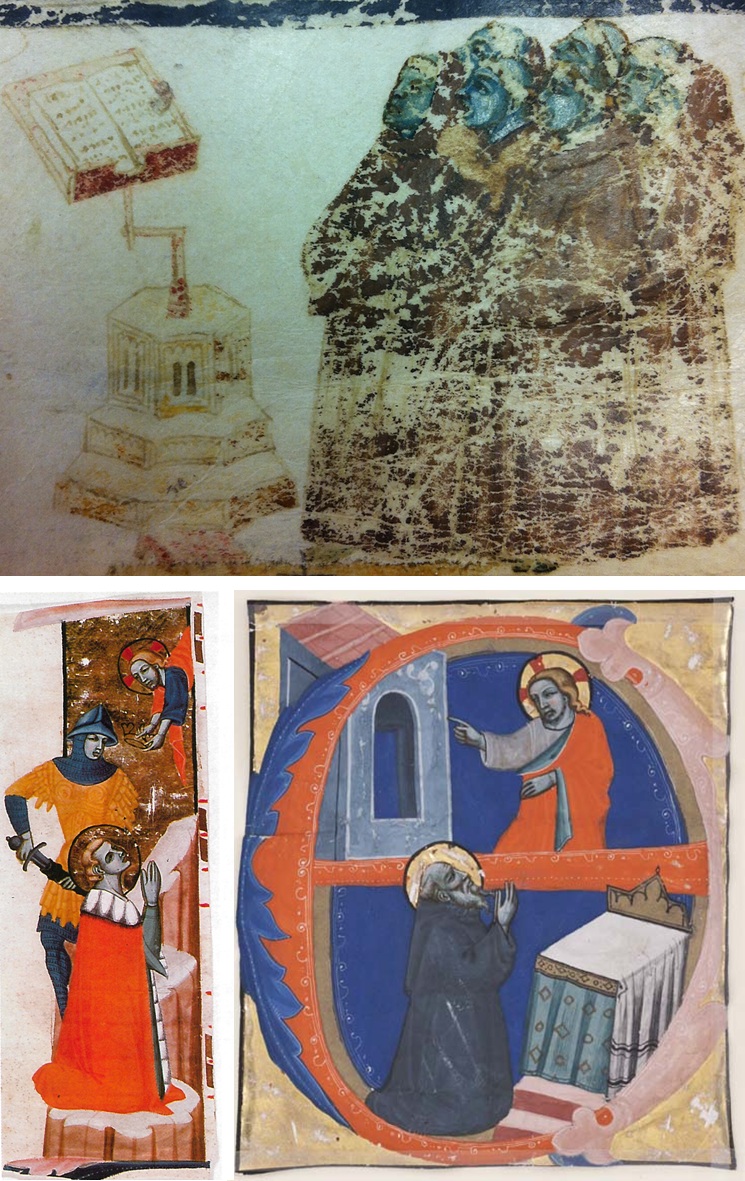

Initial A: The Resurrection, about 1335. Pistoia, Archivio Capitolare, s.s., a, inv. 488/100, fol. 1v; Initial H: The Nativity (detail), about 1335-40. Tempera colors and gold leaf on parchment, 52 x 37 cm (20 ½ x 14 9/16 in.). Impruneta, Museo del Tesoro di Santa Maria dell’Impruneta, Cod. VII, fol. 108 (Photo: Bryan C. Keene)

For the last two decades, these related but dispersed illuminations has been attributed to the Master of the Antiphonary of San Giovanni Fuorcivitas, christened by Ada Labriola after a pair of antiphonaries made for the eponymous church in Pistoia. She and others (including Pia Palladino, Gaudenz Freuler, and myself) have drawn connections between the Pistoia volumes and another important choir book set, the Impruneta Antiphonary, which also includes illuminations by the Master of the Dominican Effigies and several hands long associated with Pacino di Bonaguida (and generally called “Pacinesque”). More recently, however, Labriola hinted that the Master of the Antiphonary of San Giovanni Fuorcivitas might in fact be distinct from the anonymous artist of the Getty’s new acquisition. I agree that the two artists are in fact different—the painterly approach by the creator of the Getty miniature shows even more of a combination of Pisan and Florentine styles (whereas the Master of the Antiphonary of San Giovanni Fuorcivitas relied more directly on Pisan models).

A number of artists from Pisa were active in Florence in the first half of the Trecento, often working alongside the large team of illuminators gathered under Pacino di Bonaguida’s aegis—likely including the artist of the Getty miniature, who may have been attracted to the large book trade in Florence at the time.

Making an Attribution

Initial A: Christ Wiping the Tears from the Eyes of the Saved (detail), attributed to the Master of the Antiphonary of San Giovanni Fuorcivitas, about 1345–50. Tempera colors and gold leaf on parchment, 5 1/3 x 5 1/3 in (13.5 x 13.5 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 113, recto. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

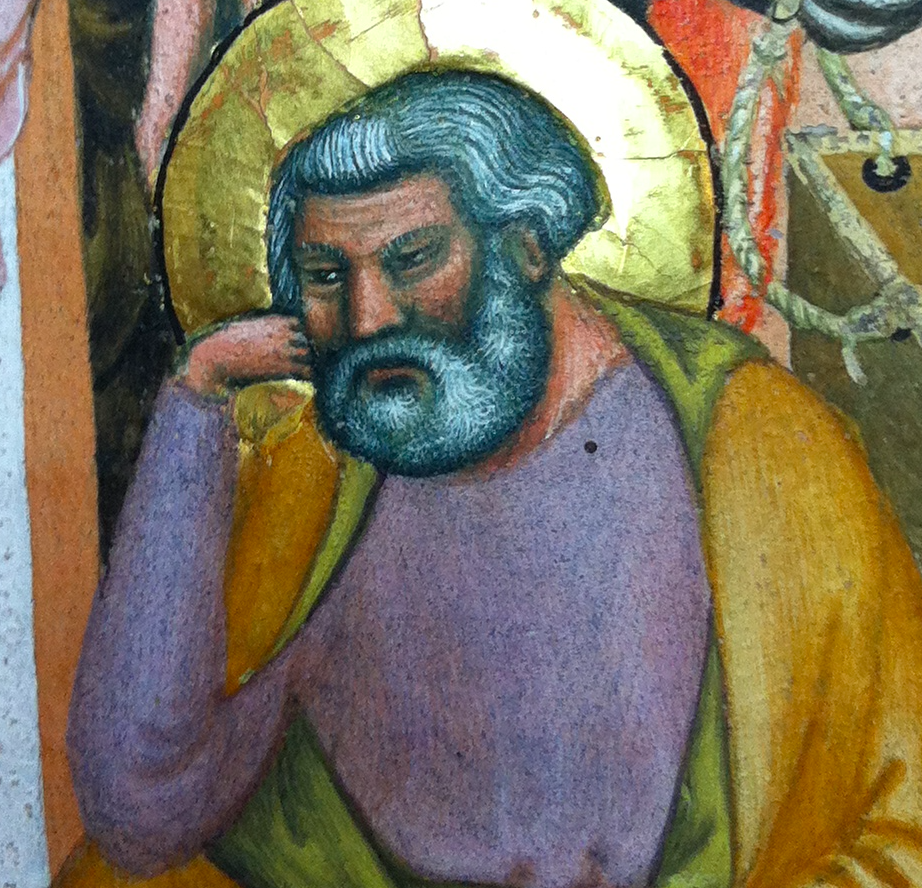

How do we know that the creator of our recently acquired leaf is not the Master of the Antiphonary of San Giovanni Fuorcivitas? One approach to differentiating the highly accomplished but still anonymous illuminator of the Getty initial, and the corresponding miniatures from a two-volume antiphonary, from the Master of the Antiphonary of San Giovanni Fuorcivitas by comparing their approaches to rendering flesh tones (an approach masterfully demonstrated in a recent essay by Nancy Turner). The elusive artist under consideration often began by applying blues and grays as base tones and shadow, then layered long and loose strokes of whites and pinks for complexion (sometimes with pink dabs to suggest rosy cheeks), and finally outlined contours (neck and jawlines, noses, ears, etc.) in brown. In Saint Peter’s face shown above, for example, the illuminator built up white strokes on a blue-gray ground, above which brown strokes indicate the jawline and cheekbones. He then layered frenetic white brushstrokes to indicate a full beard, mustache, and eyebrows.

Initial H: The Nativity (detail), Master of the Antiphonary of San Giovanni Fuorcivitas, about 1335-40. Tempera colors and gold leaf on parchment, 52 x 37 cm (20 ½ x 14 9/16 in.). Impruneta, Museo del Tesoro di Santa Maria dell’Impruneta, Cod. VII, fol. 108 (Photo: Bryan C. Keene)

The Master of the Antiphonary of San Giovanni Fuorcivitas, by contrast, preferred fine, tightly layered strokes of red, pink, and white with areas in shadow articulated with small strokes of dark gray, gray-brown, or blue-gray, as Nancy Turner has observed. The figure of Saint Joseph (above) in the Impruneta Antiphonary demonstrates this technique, in which a dense reddish-pink undercoat of paint was applied, followed by tightly grouped strokes in lighter pink and white; for the beard, a dark gray-blue zone was laid down before numerous fine white touches were added. Furthermore, the overall palette of the Master of the Antiphonary of San Giovanni Fuorcivitas stands out when compared to other contemporary illuminators (including the anonymous Getty artist) through his use of muted tones, like a distinct chartreuse (yellow-green), coral-pinks, olive-browns, and deep mineral blues (again, observed by Nancy Turner).

It is clear that the illuminator of the Getty’s new acquisition was strongly influenced by Pisan formation and models for the rendering of fleshtones. But the page layout, featuring borders with bar-and-scrolling-vines and drolleries, and the compositional models find their most direct parallels in Florence starting around 1315, as well as in Pisa, Pistoia, and Siena from about the 1330s onward.

Initial O: The Betrayal of Christ, attributed to the Master of the Antiphonary of San Giovanni Fuorcivitas, about 1345-50. Tempera colors and gold leaf on parchment, 22 x 20.7 cm (8 11/16 x 8 1/8 in.). Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, 1917.91

Although the identity of the Getty illuminator continues to challenge and at times vex the scholarly community, the particular style is quite easily recognizable. In fact, on a research trip to Boston, I encountered a leaf in the Museum of Fine Arts that has been absent from the scholarship on this artist (that is on the Master of the Antiphonary of San Giovanni Fuorcivitas). The bluish flesh tones, the treatment of drapery, landscape, and movement… all characteristic of this nameless master, and the Boston cutting can here for the first time be associated with the Getty cutting and others from the original set. The table at the end of the post highlights the other pieces that I’ve tracked down, along with those gathered over the years by scholars, all of which might helps us understand the scope of the two-volume antiphonary.

Initial A: Christ in Majesty, attributed to the Master of the Antiphonary of San Giovanni Fuorcivitas, about 1345-50. Tempera colors and gold leaf on parchment, 57.8 x 40.7 cm (22 ¾ x 16 in.). Cleveland Museum of Art, 39.677; Initial I: The Martyrdom of Saint Minias (?), attributed to the Master of the Antiphonary of San Giovanni Fuorcivitas, about 1345-50. Tempera colors and gold leaf on parchment. Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Graphische Sammlung, Bredt 39; Initial E: Saint John Gualbert (?), attributed to the Master of the Antiphonary of San Giovanni Fuorcivitas, about 1345-50. Tempera colors and gold leaf on parchment, 12.2 x 13.4 cm. Philadelphia, Free Library, 26:8

What do we know about this now-dispersed antiphonary? Based on the garments worn by certain figures on three surviving leaves or cuttings, scholars have proposed that the manuscripts were originally commissioned either by a Franciscan house (given that the choir of clerics on a page in Cleveland wear brownish habits) or by the Vallombrosan church of Santa Trinita in Florence (due to the potential presence of Saint Minias as the martyred royal figure in a cutting from Nuremberg or of the kneeling saint in a black-gray habit in a cutting from Philadelphia).

There is also the possibility that the illuminator produced two different sets of choir books for two separate religious institutions. A recently discovered cutting (sold at Sotheby’s in 2013) showing Saint Paul before a group of white-clad flagellants suggests yet another religious affiliation: a disciplinati (self-punishing) society known as the Compagnia di San Paolo. My ongoing research attempts to untangle this complex web of associations.

Lacking a name for this artist, manuscripts scholar Ada Labriola proposed a distinct oeuvre of manuscripts for this new hand:

- A pair of choir books containing the sung portions of the mass (graduals) now in the Museo Civico in Montepulciano (H/2 and Ms. I), which I was fortunate to study several years ago

- Seneca’s Epistulae ad Lucilium in the British Library (Ms. Additional 15434)

- Manfredo di Monte Imperiale’s Liber de herbis et plantis in the Bibliothèque nationale de France (Lat. 6823)

The manuscripts from the British Library and the Bibliothèque nationale, both in wondrous states of preservation, suggest that the illuminator was sought after by learned members of society to produce texts that did not have a long decorated tradition, while the Montepulciano Gradual and the dispersed antiphonary reveal commissions filled with new approaches to standard imagery for ecclesiastical communities. In Codex H/2 of the Montepulciano Gradual—likely made for an Augustinian house due to the presence of tonsured figures wearing black-gray habits—we find the coat-of-arms of the Angevin royal house surrounded by another device comprised of silver columns against a red ground and a third incomplete escutcheon.

Coats of Arms, attributed to the Master of the Antiphonary of San Giovanni Fuorcivitas, about 1345-50. Tempera colors and gold leaf on parchment. Montepulciano, Museo Civico, Ms. H/2, fol. 3v

Despite the fact that the Montepulciano volumes are missing several miniatures (including the historiated initial on the page above, likely depicting David lifting up his soul to God in an initial A), they still appear as finely preserved examples of the master’s hand. One might therefore propose the following names for our anonymous artist: Master of the Montepulciano Gradual (we might perhaps add H/2 or I to distinguish from the other choir books on display in that museum; I is preferable due to the current state of preservation) or Master of the Angevin Gradual. Since the commission of the manuscript to which the Getty leaf once belonged was likely undertaken for a Vallombrosan house, possibly the Church of Santa Trinita in Florence, one might refer to the artist as the Master of the Vallombrosan Antiphonary or more tenuously the Master of the Santa Trinita Antiphonary. However, I’m still engaged in a thorough study of all the leaves and cuttings from this set with the hopes of better determining the books’ original state, contents, and place of use before committing to a name.

We have much still to learn about this anonymous illuminator. Other mysteries remain, such as the artist’s formation and training and the location of the artist’s shop.

The recent appearance of several fragments at auction promises that more pieces to this puzzle may yet surface, and in the meantime, I plan to continue studying this hand and refining an understanding of the shop that was once commissioned to create such wondrous liturgical manuscripts.

Illuminations newly associated with the Getty initial and with related miniatures: Initial D: Saint Agnes Appearing to Her Parents, Stockholms Auktionsverk, Dec. 15, 2015, lot 6009; Initial M: The Annunciation, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Robert Lehman Collection, 1975.1.2478; Initial O: The Betrayal of Christ, Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, 1917.91; Initial S: Christ Before the High Priests, Paris, Private Collection, formerly Jörn Günther; Initial I: A Martyr Saint, London, Christie’s, 1 December 2015, lot 10

Table of surviving leaves and cuttings from a two-volume antiphonary, perhaps made for a Vallombrosan church

The following list is based on years of research by scholars like Ada Labriola, Pia Palladino, and Gaudenz Freuler. Those items in bold and underlined are recently or newly associated with this set.

Temporal Cycle—feasts that celebrate events from Christ’s life, often with certain saints’ feast days |

||

| 1 | Initial A: Christ in Majesty Cleveland Museum of Art, 39.677 |

First Sunday of Advent Aspiciens a longe |

| 2 | Initial S: The Stoning of Saint Stephen Prague, Nardoni Galerie, n. K28 040 |

Feast of Saint Stephen, Dec. 26 Stephanus autem plenus gratia |

| 3 | Initial E: Saint John the Baptist London, Private Collection |

Octave of Christmas Ecce agnus Dei |

| 4 | Initial D: David Kneeling before Christ Philadelphia, Free Library, 74:2 |

First Sunday after Epiphany Domine ne in ira tua arguas me |

| 5 | Initial D: God the Father Appearing to Noah Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Graphische Sammlung, Bredt 38 |

Sexagesima Sunday (or Quinquagesima Sunday) Dixit Dominus ad Noe |

| 6 | Initial L: Christ Appearing to Abraham Philadelphia, Free Library, 74:3 |

Quinquagesima Sunday Locutus est Dominus ad Abram |

| 7 | Initial M: The Annunciation New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Robert Lehman Collection, 1975 (1975.1.2478) |

Feast of the Annunciation, March 25 Missus est Gabriel |

| 8 | Initial I: Christ on the Mount of Olives Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Graphische Sammlung, Bredt 39 |

Maundy Thursday In Monte Oliveti |

| 9 | Initial O: The Betrayal of Christ Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, 1917.91 |

Good Friday Omnes amici mei derelinquerunt |

| 10 | Initial S: Christ Before the High Priests Paris, Private Collection (formerly Jörn Günther) |

Holy Saturday Sicut ovis ad occisionem ductus est |

| 11 | Initial A: The Resurrection and the Three Marys at the Tomb New Haven, Conn., Yale University Art Gallery, 1954.7.1 |

Easter Sunday Angelus Domini descendit de celo |

| 12 | Initial I: A Priest before an Altar Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Graphische Sammlung, Bredt 40 |

Corpus Domini Immolabit haedum multitudo |

Sanctoral Cycle—feasts that commemorate saints’ lives |

||

| 13 | Initial S: Saint Peter Enthroned Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Graphische Sammlung, Bredt 41 |

Feast of the Chair of Saint Peter, Jan. 18 Symon Petre antequam de navi |

| 14 | Initial D: Saint Agnes Appearing to Her Parents Stockholms Auktionsverk, Dec. 15, 2015, lot 6009 |

Feast of Saint Agnes, Jan. 21 Diem festum sacratissime virginis |

| 15 | Initial A: The Presentation in the Temple London, Collection of Robert McCarthy (ex–Korner Collection; Sam Fogg) |

Feast of Purification, Feb. 2 Adorna thalamum tuum Syon |

| 16 | Initial D: The Martyrdom of Saint Agatha London, private collection |

Feast of Saint Agatha, Feb. 5 Dum torqueretur beata Agatha |

| 17 | Initial Q: The Conversion of Saint Paul Location unknown |

Feast of Saints Peter and Paul, June 29 Qui operatus est Petro |

| 18 | Initial S: The Birth of the Virgin Cologne, Wallraf- Richartz Museum, M207 |

Feast of the Birth of the Virgin, Sept. 8 Sancta Dei Genetrix Virgo |

| 19 | Initial I: The Martyrdom of a Saint (Saint Minias?) Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Graphische Sammlung, Bredt 39 |

Feast of Saint Minias (?), Oct. 25 [chant uncertain] |

| 20 | Initial D: The Calling of Saints Peter and Andrew Jörn Günther Antiquariat |

Feast of Saint Andrew, Nov. 30 Dum perambularet Dominus |

Commons (most likely at the end of the sanctorale volume) |

||

| 21 | Initial A: Christ Wiping the Tears from the Eyes of the Saved Los Angeles, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 113 (ex-Zeileis collection, sold Koller Zurich, 18 September 2015, lot 122) |

Common of Martyr Saints Absterget Deus omnem lacrimam ob oculis sanctorum |

| 22 | Initial I: A Martyr Saint London, Christie’s, 1 December 2015, lot 10 |

Matins for the Common of One Martyr In lege Domini |

| 23 | Initial E: Saint John Gualbert (?) Philadelphia, Free Library, 26:8 |

Common of one confessor Euge serve bone et fidelis |

| 24 | Initial E: A Bishop-Saint Philadelphia, Free Library, 26:9 |

Common of one confessor bishop Euge serve bone et fidelis |

| 25 | Initial E: Christ and the Apostles Philadelphia, Free Library, 26:10 |

Common of the Apostles [?] Ecce ego mitto vos sicut oves in medio luporum |

| 26 | Initial E: Saint Paul Before a Group of Flagellants Paris, Sotheby’s, 8-9 April 2013, lot 225 |

Ergo fratres debitores sumus |

Beautiful illumination. I wonder if the vial is a reference to Psalm 56:8: “… put thou my tears into thy bottle …”–meaning that God keeps an account of the tears of his faithful ones.

Have you looked at painters of the Riminese school? The facial features of many of these figures remind me of Giovanni Baronzio, although the blue color is not something often seen in the Riminese works I know. The early 14th century Riminese artists were fairly itinerant and their works often contain elements reminiscent of Umbrian and Tuscan works, so there may simply be some common influences. But, if you have not already discounted them they might be worth a look.

Very interesting. Thank you. Bryan, Would you happen to know of a cutting by the Dominican Effigist that appeared in a small French exhibition about 10 years ago? The subject was the Purification. It closely resembled this imitation: http://digital.tcl.sc.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/pfp/id/793/rec/4

I would love to know more about it, as I need to cite it in a forthcoming book.

Dear Victoria, Alison, and Scott,

Thank you for your wonderful comments and engagement with the post.

Victoria, I like the association to Psalm 56 and the connection to the Revelation passage about drying tears is great.

Alison, spot on! The Riminese school has long been on my mind in relation to early Trecento art in Florence. Several of the great illuminators there were at one time associated with Rimini! I will have an opportunity to study a few Baronzio works in the next year and will of course pay attention to his flesh tones.

Scott, I do know the miniature and will write to you anon.

Best,

Bryan (Assistant Curator of Manuscripts, Getty Museum)

Thank you Bryan. As regards the re-naming of the anonymous artist, at the moment a good choice could be “Master of the Montepulciano Gradual”. As you well know, the provenance from the Vallombrosan church of Santa Trinita in Florence is just a hypothesis. Your research on the Master and his set of liturgical “fragments” is important and useful: much must be still discovered on the provenance of his illuminations and the context in which he worked.