Art historians love books. And why not? Books are critical to our work. We need publications to conduct research, communicate what we learn, and present our arguments, discoveries, and insights.

While printed books are not going away anytime soon, digital platforms are providing exciting new possibilities for the creation and sharing of art historical research. These new possibilities are evident in the Getty Research Institute’s first born-digital publication, Pietro Mellini’s Inventory in Verse, 1681, edited by Murtha Baca and Nuria Rodríguez Ortega, with notes and essays by Baca, Ortega, Francesca Cappelletti, and Helen Glanville.

This publication is a critical digital facsimile of a seventeenth-century manuscript, an inventory of artworks in the collection of the Mellini family in Rome. It is based on research that began in the innovative online collaborative environment known as The Getty Scholars’ Workspace™, which is currently being developed though generous partnership support from the Seaver Institute.

The 1681 poetic inventory, part of the Research Institute’s Special Collections, is the subject of the digital publication.

The product of five years of work by a multi-disciplinary team, the open-access web publication allows users to zoom in on high-res images of the manuscript, compare its pages side by side with Italian transcription and English translation, explore expert commentary on individual lines, read 13 short essays, and more.

The Mellini manuscript is a quirky one. As Baca notes in her essay “The Manuscript, and the Poem,” the document “is a hybrid of two very different types of texts: a poem (by a mediocre writer) strewn with literary and cultural allusions, and an inventory of works of art—a legal document that was typically drawn up during the process of settling a decedent’s estate.” In the 13 short essays, Baca and her co-authors explore this unusual document, explaining its history, purpose, context, and relationship to a legal inventory of the same art collection that was drawn up just the year before. Pietro Mellini’s Inventory in Verse, 1681 provides insight into the collecting practice of elite Roman families of the Baroque period and into the important role that inventories played in the fashioning of these families’ public identities.

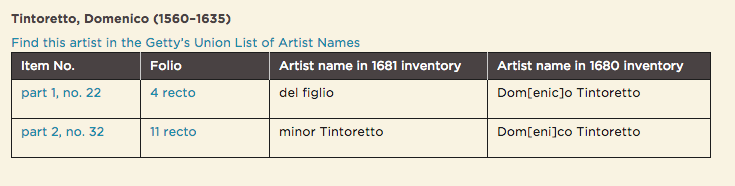

However, Pietro Mellini’s Inventory in Verse, 1681 is more than an analysis of a rare document or art historical text. Like the manuscript that is its focus, this born-digital publication is both hybrid and unique. Unlike a more conventional, printed publication, which might limit itself to the discussion of the Baroque art or to collecting practices, this digital publication presents the information gleaned from the 1680 legal inventory and the 1681 poetic inventory in a way that takes advantage of the non-linear and hyperlinked environment of the web. For example, Baca and Ortega do not simply provide a list of the artists mentioned in the inventory, but provide these artists’ names as controlled vocabulary, linking the names as they appear in the inventory (often with alternate spellings) to the Getty’s Union List of Artist Names (ULAN)®. Similarly, the publication’s “List of Artworks” section provides information about the works in the inventory as well as art historical analysis of them, but also indicates what each work depicts using Iconclass subject categories.

Like Pietro Mellini himself, the authors of this digital publication have presented something more than simply a flat or static list of data. Instead, Baca and her colleagues have created a multi-layered and dynamic compilation of data and metadata that exposes the web of knowledge, of which Mellini’s 1681 inventory is just one part.

The entry for Domenico Tintoretto in the artist list links to his record in the ULAN database, as well as to the specific pages in the 1681 inventory where he is mentioned, even when he is referred to in oblique terms such as “son of” or “younger Tintoretto.”

In a pop-up “Scholar Note,” Murtha Baca and Helen Glanville discuss the various translation possibilities for the phrase “di sua fama…il chiaro suono” in Folio 2, verso of Mellini’s manuscript.

Digital art historical publications such as Pietro Mellini’s Inventory in Verse, 1681 offer new possibilities not only for sharing the product of research, but also illuminating the process by which it is created. For example, the publication reveals debates between scholars, preserved within the annotations of the manuscript. Where Baca translates “di sua fama . . . il chiaro suono” in Folio 2, verso as “the clear sound of his fame,” Glanville suggests “his resounding fame.” Baca responds with a third option: “his clarion fame.” The exchange exposes the discursive aspects of art historical research, interpretation, and argumentation, as well as the subjective nature of translation work.

Finally, Pietro Mellini’s Inventory in Verse, 1681 illustrates the possibilities of research and analysis in art history, but also its limits. A glance at the “List of Artworks,” for example, reveals just how few of the inventory’s 90 works the research team was able to securely identify. The digital publication illustrates clearly that the practice of art history is as much about revealing what is unknown as it is about explaining what is known.

With Pietro Mellini’s Inventory in Verse, 1681, we at the Getty Research Institute hope to increase access to an object in our collection and offer a model for digital art historical publications that reflects multiple scholarly perspectives. The Research Institute’s effort to forge new paths in the field of art history, which this publication represents, fits within its larger mission of producing innovative research and scholarship that expand the possibilities, and the reach, of the field of art history.

Comments on this post are now closed.